“Bhopal”

For health and safety activists and public health people, that word sends shivers up our spines. Thinking of the disaster — where thousands died and many more thousands continue to suffer decades later — and the potential for similar disasters in the future.

What I’ve found however, is that young people these days don’t know about Bhopal. The word “Bhopal,” the city where the tragedy took place in India 34 years ago means nothing.

But what happened at Bhopal should never be forgotten, and as EPA, OSHA and various state governments look at revising their chemical plant safety regulations, they need to remember the lessons of Bhopal and how to make sure that it never happens again.

To remind us — and to educate those younger — I’m reprinting a post I wrote in 2004 — on the 20th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster:

20th Anniversary of Bhopal

Twenty years ago today, at 5 minutes past midnight, water leaked into a tank containing 40 tons of methyl isocyanate at a Union Carbide pesticide plant in the city of Bhopal, India. Every mechanism that could have controlled the resulting gas cloud had been shut down, disconnected or was otherwise in use.

The result:

“The Hiroshima of the chemical industry.”

The “worst corporate crime in history.”

It’s surprisingly hard to know what to write about this seminal event of the 20th century. Even the above characterizations hardly do justice to this catastrophe whether you’re looking at the raw numbers, the individual stories or the aftermath.

How to mark this day? After reading about the continuing suffering in Bhopal and the continuing refusal of those responsible to hold themselves accountable for these crimes, I think perhaps a day of rage may be more appropriate than a moment of silence.

Clear your mind and try to think about what happened tank release You can start by looking at the devastating statistics.

- Dow Chemical (which bought Union Carbide, the Bhopal plant’s original owner) claims that “only” 3,800 people were killed. (Carbide had originally claimed that exposure to methyl isocyanate was no worse than tear gas)

- Indian officials say 10,000 to 12,000 people were killed.

- Bhopal activists and health workers say more than 20,000 people have died over the years due to gas-related illnesses, such as lung cancer, kidney failure and liver disease.

- Indian officials estimate that nearly 600,000 more have become ill or had babies born with congenital defects over the last 20 years

Or, if the statistics are too much to comprehend, you can listen to just one of the many thousands of individual stories:

On the night her world changed forever, Rashida Bee was 28 years old and had already been married for more than half her life. Her parents, traditional Muslims, had selected her husband for her when she was 13. He worked as a tailor, and they lived together in her parents’ modest home in the industrial city of Bhopal, in central India. Bee hadn’t learned to read or write, and she ventured out of the house only when escorted by a male relative. It was nevertheless a full life; her extended family of siblings, nieces and nephews numbered 37 in all.

The fateful night came on a Sunday. Bee and her family had gone to bed after sharing a simple supper. But shortly after midnight, in the early hours of Dec. 3, 1984, Bee was awakened by the sound of violent coughing. It was coming from the children’s room. “They said they felt like they were being choked,” Bee later told the online environmental magazine Grist, “and we [adults] felt that way too. One of the children opened the door and a cloud came inside. We all started coughing violently, as if our lungs were on fire.”

From out on the street came the sound of shouting. In the light of a street lamp, Bee saw crowds of shadowy figures running past the house. “Run,” they yelled. “A warehouse of red chilies is on fire. Run!”

A few blocks away, a woman who would later become a dear friend of Bee’s was also running for her life. Champa Devi Shukla, a 32-year-old Hindu, lived down the street from the pesticide factory owned by Union Carbide. She knew better than to believe the rumors about a warehouse fire. “We knew this smell because Union Carbide often used to release these gases from the factory late at night,” Shukla later told me. “But this time it went on longer and stronger.”

Shukla was right. An explosion inside the Union Carbide factory had sent 27 tons of methyl isocyanate gas wafting over the city’s shantytowns. “The panic was so great,” said Shukla, “that as people ran, mothers were leaving their children behind to escape the gas.”

In the pandemonium, Bee too was separated from most of her family. She found herself running with her husband and father, but they didn’t get far. “Our eyes were so swollen that we could not open them,” she recalled. “After running half a kilometer we had to rest. We were too breathless to run, and my father had started vomiting blood, so we sat down.”

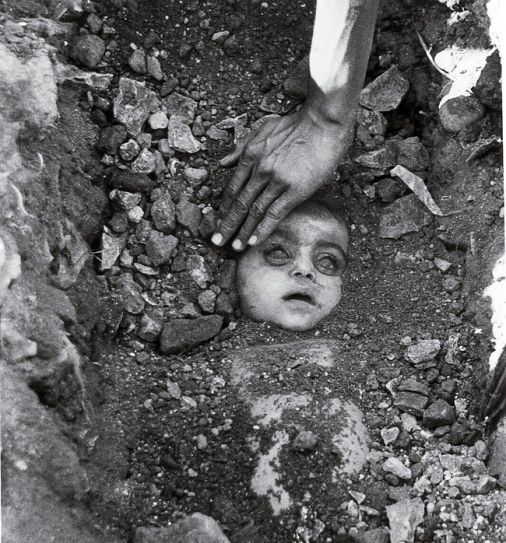

The scene around them was apocalyptic. There were corpses everywhere, many of them children. Those people still alive were bent over double or splayed on the ground, retching uncontrollably or frothing at the mouth. Some had lost control of their bowels, and feces streamed down their legs.

Exactly how many people died that night will never be known; many corpses were disposed of in emergency mass burials or cremations without documentation. Bee remembers that as she searched for family members in the following days, “I had to look at thousands of dead bodies to find out if they were among the dead.”

(Bee and Shukla later became activists and earlier this year received the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, as well as an award from the Occupational Health Section of the American Public Health Association. For years, they’ve been organizing protests and demanding that Dow and Union Carbide be held responsible for the cleanup and compensation. )

So where are we now, twenty years later? In the United States, home of Union Carbide (and Dow, which bought Union Carbide in 2001) we have established the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board to investigate chemical incidents and make recommendations designed to prevent them. Congress has passed the 1986 Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know-Act which requires companies to disclose details of the types and amounts of chemicals stored at their facilities, better planning by industry and local officials to respond to chemical leaks, and it created the Toxics Release Inventory, the successful program to force reductions in chemical emissions by publicizing emissions data from local plants. In 1992, OSHA has issued the Process Safety Management standard which requires companies using dangerous quantities of highly hazardous chemicals to implement management systems to prevent catastrphic releases.

So have we resolved all the of issues raised at Bhopal? Charolyn Merritt, Chairman of the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investgation Board isn’t so sure:

The same kinds of backup failures and lack of disaster preparedness that contributed to Bhopal still exist, said Carolyn Merritt, chairman of the chemical safety board.

“Over and over again, we see companies _ even those covered under process safety rules _ committing the same kind of management errors, mechanical errors and process errors that set up the facility at Bhopal for the accident that occurred,” she said.

“Bhopal was not a technical unknown. It was because of failures to maintain systems and employees not knowing what to do and having backup and systems that actually worked to prevent this. We have that same thing here. We investigate it every single day,” Merritt said.

Dr. Gerald Poje, who just ended his second five-year term on the chemical safety board, agrees:

He said the U.S. chemical industry, as well as the Occupational Health and Safety Associaton (sic) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have taken monumental steps to improve safety since Bhopal _ but far less than needed.

He said a 2002 CSB study found that uncontrolled chemical reactions _ like the mixture of water and methyl isocyanate that, with failed safety measures, led to the Bhopal release _ caused 167 accidents in the U.S. from 1980 through 2001 that killed 100 people. The board recommended that OSHA and the EPA expand regulations to cover chemical reactions in addition to listing chemicals based on their individual properties _ such as whether they are toxic, corrosive or flammable _ but no such action has been taken.

“I wish I could tell you that was 20 years ago and everything has worked out well since (Bhopal),” Poje said. “I’ve seen all too often the same underlying situations result in tragedies here in the U.S. They involve big and small corporations, and communities seem unaware of hazards in their midst.”

Poje notes that even with the leak, the cloud of deadly methyl isocyanate fumes could have been controlled before killing thousands:

Poje said the disaster began shortly after midnight when water entered a storage tank containing the gas, causing a heated reaction.

The unit containing methyl isocyanate was supposed to be refrigerated, but it was turned off and refrigerant had drained — so when the mixture heated up, nothing cooled it down, he said.

Pressure built. A storage tank designed to relieve such pressure by accepting some of the mixture was already full, against all safety operations and protocol, Poje said. A scrubbing unit to catch the flow of dangerous material wasn’t working.

A flare unit designed to burn off any toxic gas if those previous safety measures failed also was out of operation, he said.

Workers at the plant had little to no training regarding how to handle such a chemical reaction, Poje said. Nearby residents were equally unaware of what to do once the gas was released.

***

And the thousands of unsuspecting residents who lived near the plant should have been trained as to what to do when the unthinkable happened, he said.

“Some who had the ability to put wet rags over their mouths fared better than those who ran out into the night with no protection, no way to avoid continued exposure,” Poje said.

The Culture of the Chemical Industry?

Gary Cohen, executive director of the Environmental Health Fund in Boston points to other lessons from Bhopal

Bhopal has rightly been called the Hiroshima of the chemical industry. Bhopal not only represents the stark story of the human fallout from a chemical factory explosion but offers up important lessons about the culture of the chemical industry and its approach to security and public health.

The sad reality is that we continue to learn about chemicals by allowing industry to expose large numbers of people to them and seeing what happens.

In this way, we have learned about dioxin contamination by letting Dow, Monsanto, and other chemical companies expose American soldiers and the entire Vietnamese population to Agent Orange. We have learned about asbestos by killing off thousands of workers with lung disease. And we have learned about the long-term effects of methyl-isocyanate after Union Carbide gassed an entire city in India.

Since the Bhopal disaster, we’ve learned that we all carry the chemical industry’s toxic products in our bodies. Every man, woman, and child on the planet has a body burden of chemicals that are linked to cancer, birth defects, asthma, learning disabilities, and other diseases.

Since Sept. 11 we have also learned that in addition to our routine chemical exposures, chemical factories are perfect targets for terrorists. According to federal government sources, there are 123 chemical facilities nationwide that would put at least 1 million people at risk if they accidentally exploded or were attacked by terrorists. Some of these chemical factories are located in major cities. Yet the chemical industry continues to resist any meaningful regulation that would require them to replace the most dangerous chemicals with safer alternatives.

Bhopal Today

Meanwhile, in India thousands of demonstrators are planning a march and public meeting

Thousands of demonstrators planned to march through the main streets of Bhopal, the capital of the state of Madhya Pradesh, on Friday before holding a public meeting outside the abandoned Union Carbide plant.

U.S. chemical company Union Carbide Corp., which was bought by Michigan-based Dow Chemical Co. in 2001, paid $470 million in compensation under a settlement with India’s government in 1989. But only part of that amount has reached the victims.

“We will burn effigies of Union Carbide and Dow Chemical to voice our protest. These two companies have betrayed the victims of Bhopal,” said Rashida Bee, a disaster survivor who heads a women victims’ group.

Bee said the protesters would conclude Friday’s rally with a mass pledge to keep up the fight until victims’ demands for compensation, medical care and rehabilitation are met.

The protesters also called on Dow Chemical to clean up the plant site, where rusted pipes and pesticide storage tanks have collapsed or ruptured in the years since the plant was abandoned after the disaster.

A Second Disaster Brews

Twenty years later later, the site still hasn’t been cleaned up and Bhopal residents continue to sicken due to contaminated water and air:

Two decades later, studies show a second poisonous onslaught brews underground.

The warm rain of 20 monsoon seasons has washed an assortment of toxics left at the decaying Carbide factory into the groundwater of the same slums that bore the brunt of the gas leak, according to government and independent studies. Lawsuits aimed at getting the site cleaned up, and compensation to victims of the contamination, continue to inch through Indian and U.S. courts.

On a recent afternoon in Atal Ayub Nagar, a polluted slum, a circle of women waited their turns to fill plastic jugs at a well, while two grimy boys hunched shin-deep in a tiny black pond fished out discarded food. Studies have shown the neighborhood’s water contains a mix of such poisons as lead and mercury and volatile organic compounds known to attack the liver, kidney and nervous system.

Inam Ullah, crouching on the porch of his burlap-roofed hut, says his body has shrunk by 30 pounds since he moved to the area 12 years ago. A searing pain in his stomach finally sapped the strength he needed to push his vegetable cart, so the 50-year-old was forced to pull his two boys from school and put them to work as day laborers.

He says he believes it is the water that plagues his stomach and killed his wife last year.

“My wife has died,” says Ullah, his dark eyes glassy. “We will die also.”

Bhopal, a city of more than one million once famed for its glistening lakes and jungles, as well as the resplendent Taj-ul-Masjid, one of the country’s biggest mosques, is better known now as the city of poison.

In the years after the gas leak, as Bhopal sought to grasp its epic toll, few paid close attention to the toxic mess at the abandoned factory. Some cleanup was done – Carbide says $2 million was spent on waste removal in the first 10 years after the disaster – yet it remains today a hulking industrial sore. Strewn among the ghostly, 90-acre landscape of rusted pipes and crumbled warehouses lie hundreds of tons of pesticides and other toxic elements stored in open drums and heaps of splitting, white sacks.

Responsibility and Accountability

Meanwhile, Dow Chemical, which bought Union Carbide in 2001, continues to evade responsibility for the lingering fallout of the tragedy:

Union Carbide blames a disgruntled employee who it says sabotaged the plant. Indian investigators accuse Carbide of faulty safety mechanisms.

Carbide calls the accident a “terrible tragedy which understandably continues to evoke strong emotions even 20 years later.”

The company, based in Danbury, Conn., and bought by Dow Chemical Co. of Midland, Mich., in 2001, says it spent more than $2 million to clean up the plant from 1985 to 1994, when it sold its stake in Union Carbide India Ltd. It rejects notions that the plant and its surrounding area are contaminated.

But the environmental group Greenpeace and the government of Madhya Pradesh (of which Bhopal is the capital) both found contamination of the soil and groundwater, which Greenpeace says would cost $30 million to detoxify. The government owns the property but has done little to clean it up.

In 1989, the Supreme Court of India ordered Union Carbide to pay a final settlement of $470 million in compensation for gas victims and agreed to drop criminal charges against the company’s then-chairman Warren Anderson.

But the court reinstated charges of manslaughter against Anderson in 1991; the charges still stand. The U.S. State Department rejected India’s extradition request.

“Union Carbide has contributed significantly in providing aid to the victims and has fulfilled every responsibility and obligation it had in Bhopal,” says the company’s Web site.

But Rajan Sharma, the attorney representing plaintiffs in the lawsuit in New York, said Union Carbide put little value on the lives of people in the developing world. He said the company cut costs in India and did not observe the same safety standards it used in a similar plant in Virginia.

Dow Chemical — one of the world’s largest chemical manufacturers, which recently posted quarterly sales of $10 billion — says the responsibility for Bhopal now falls to the Madhya Pradesh government.

“Bhopal is the worst corporate crime in history,” Sarangi said. “Bhopal sent an ominous message that foreign corporations can come in and get away with whatever they can. Dow Chemical should face trial in India.”

Cohen, of the Environmental Health Fund, said the United States would never allow a foreign company to get away with a Bhopal on American soil.

“Bhopal is etched in people’s memories the way 9/11 is etched in people’s memories in New York,” Cohen said. “If you go to New York today, people are going on with their lives . . . but you know ground zero is still there. The difference is ground zero was cleaned up in nine months. Union Carbide is as it was.”

Victims of the gas leak are still awaiting their due. Because of legal maneuvering and what Cohen calls the “Kafkaesque” Indian bureaucracy, only part of the $470 million paid by Union Carbide has gone to the people who need it.

The rest has been sitting in a government bank, accruing interest. It is now worth $330 million.

Even Amnesty International has come out with a major report, called Clouds of Injustice, emphasizing the the massive violation of human rights — taking away peoples lives and health — and charging Union Carbide with ignoring basic safety precautions and avoiding legal and financial responsibility.

As environmental journalist Mark Hertsgaard describes it:

Amnesty International has urged Dow Chemical, as Union Carbide’s new corporate parent, to take a series of actions to make amends. Those actions include paying for a full cleanup of the Bhopal site and its contaminated groundwater, standing trial as requested in India, and paying full economic, medical and environmental reparations to the victims. More broadly, Amnesty echoes activists’ call for tougher regulation of chemical production, especially in impoverished communities and countries. “Clouds of Injustice” proposes that the United Nations adopt an “international human rights framework that can be applied to companies directly” to ensure “transparency and public participation in … the operation of industries using hazardous materials.”

Meanwhile, in Bhopal, people continue to suffer and die:

Activists want Union Carbide to release the exact chemical composition for MIC, which they say has been like asking Coca-Cola for its secret formula. If they had that information, the activists say, health experts could then work on a viable antidote for those who still have MIC in their bloodstream.

Another problem is a lack of proper monitoring of patients. It’s not there now; it wasn’t there at the time of the accident, said Jeffrey Koplan, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who led one of the few foreign medical investigation teams in Bhopal five days after the disaster.

“At the time, people were fleeing. Bhopal became a ghost town,” Koplan said. “You could tell where the cloud of gas had been. It looked like fall. There weren’t any leaves left on the peepal trees.”

Many Bhopalis exposed to the gas were not identified properly, Koplan said. The dead had been buried or cremated before identification.

Koplan called the immediate medical response in Bhopal “heroic.” But he questioned actions taken in the years that followed. Where was the documentation of deaths, of survivors? Where was the proper care?

“Bhopal was unique in a lot of ways,” Koplan said. “After all, here was this new, toxic substance in a heavily populated area. We had not dealt with something like that before.”

So what message can we take away from Bhopal? In a sense, Union Carbide’s actions were not unusual, cutting a few corners, slacking off on recognized safe procedures, hoping for the best. We see it every day, except that usually not much happens or maybe one or two workers get killed. What we’re talking about here is responsibility — corporate responsibility, and the responsibility of governments to make sure that corporations act responsibly. In this era of expanding globalization, however, the task becomes much more difficult.

Amnesty may sum it up best:

The Bhopal case illustrates how companies evade their human rights responsibilities and underlines the need to establish a universal human rights framework that can be applied to companies directly. Governments have the primary responsibility for protecting the human rights of communities endangered by the activities of corporations, such as those employing hazardous technology. However, as the influence and reach of companies have grown, there has been a developing consensus that they must be brought within the framework of international human rights standards.

And finally, look homeward. The issue of chemical plant safety is again being raised as homeland security concerns focus attention not only on the vulnerability of plants to terrorist attacks, but at the inherent dangers of the chemical industry, especially for plants located near highly populated areas. I point you to a little noticed incident last June when Gene Hale and her daughter, Lois Koerber died from exposure to chlorine fumes over a mile away from where two trains collided releasing a deadly cloud of chlorine gas. Sometimes late at night I think about this accident as I listen to the freight trains passing less than half a mile from my home. Tonight, at five minutes after midnight, I’m thinking about Bhopal, as well.

West Virginians should think of Bhopal because Union Carbide was behind America’s largest worker health disaster, which occurred in Gauley Bridge, West Va. Some 1,600 workers died of silicosis building a tunnel where Union Carbide’s contractors hired five undertakers to handle the massive number of (preventable) deaths.

Appreciate your thoughts about the Bhopal Disaster. I wrote a detailed comparison of the double standards between Carbide plants in Bhopal and West Virginia, published 1985, and would like to share it with you. Where can I send this as pdf?