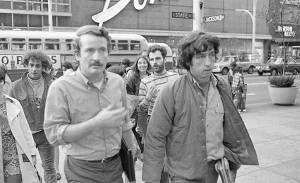

Sad days. John Froines died last week at age 83. He had had been suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

Froines was best known to Americans of a certain age as one of the Chicago 7, a group that included Tom Hayden, Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman and Rennie Davis, who were indicted under federal charges of crossing state lines to incite a riot during the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. In 1970 the jury acquitted Froines and Weiner of all charges. An appeals court later dismissed most of the charges against the others.

But to workplace safety and health activists, Froines is best remembered as an workplace health advocate and environmental scientist who helped shape government standards on lead and clean air, particularly in impoverished neighborhoods.

After the Chicago festivities, Froines remained politically active, although not in the same way. Speaking in a 1990 LA Times interview about his transition from activist to scientist, Froines remarked that “We still need student protesters because many of the problems of the ‘60s continue and new issues have emerged,” he told The Times shortly after he was named director of UCLA’s Occupational Health Center. “But nobody’s a student activist at 50. You’d have to have your head examined.”

Instead of anti-war work, Froines channeled his energy in other directions: mainly workplace safety. He headed first for Vermont where, “as head of the occupational health division of the Vermont Health Department, he helped persuade the state’s nuclear power industry to accept health standards tougher than federal regulations.”

In the late 1970s, he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the first head of the Office of Toxic Substances in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, but despite his bureaucratic status, he retained the fervor and activism that marked his youth.

“I haven’t changed,” he told the Sun-Times in 1979. “We’ve gone a long way toward protecting working people since I’ve been here and I don’t think that’s really so different; it still represents a social commitment.”

At OSHA he worked on standards reduce workers exposure to lead and cotton dust in the workplace. After his stint at OSHA,

Dr. Froines went on to serve as the deputy director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In 1981, Dr. Froines took a position at the University of California at Los Angeles as a professor of toxicology. He remained at the university for more than 30 years, directing the Center for Occupational and Environmental Health and leading research into areas such pesticide contamination, diesel pollution and air quality at landfills.

At UCLA,

Froines conducted a study to determine which Southern California jobs and industries had the highest exposure to 500 different chemicals. And as head of the UCLA’s Occupational Health Center, he oversaw a study to determine how some industrial chemicals cause early aging of the brain and how others help trigger the first stages of cancer.

John was also an environmental justice advocate.

He engaged with communities hit hard by industrial pollution and smog, tailoring his research to their needs and even accompanying neighborhood groups to meet with government and corporate officials.

“When you walk into a room with an internationally recognized expert on an issue, it makes a difference,” Angelo Logan, co-founder of one such organization, the California-based East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, said in a phone interview. “John’s work was driven, driven to make real differences in people’s lives.”

Froines is survived by his wife, Andrea Hricko, a daughter, Rebecca Froines Stanley; a son, Jonathan Froines; and two granddaughters, Kayla and Jessica Stanley. Hricko is also a long-time workplace safety and health advocate.

John Froines was an American hero ! May he rest in peace.

Sad news! John was a bright, interesting and engaging professional who seldom had lukewarm feelings about anything that he chose to consider. We came to OSHA headquarters during Eula Bingham’s tenure as assistant secretary, and met by chance while both grazing on salads at the Frances Perkins Building’s 6th floor cafeteria.

His Dad had apparently been a shipyard worker (in San Francisco, I think), and my new position in the agency’s Maritime Standards office became the basis of our discussions and our relationship. I was sad to see him “bail out” when the Reagan administration took office, but completely understood his rationale.

Guys like John don’t often appear in one’s life, and I glad I had the opportunity to get to know him. Rest in Peace partner.

What an interesting and inspiring journey…