COVID Keeping Millions of Workers Off the Job

COVID continues to take a major toll on the economy, and specifically on the labor force, according to recent studies. In January, a Brookings Metro report that assessed the impact of long Covid on the labor market and found conservatively that 1.6 million full-time equivalent workers could be out of work due to long Covid. With 10.6 million unfilled jobs at the time, long Covid potentially accounted for 15% of the labor shortage. And last June, the Census Bureau conducted a study showing that:

- Around 16 million working-age Americans (those aged 18 to 65) have long Covid today.

- Of those, 2 to 4 million are out of work due to long Covid.

- The annual cost of those lost wages alone is around $170 billion a year (and potentially as high as $230 billion).

The situation can get worse unless actions are taken, including better prevention and treatment options, expanded paid sick leave, improved employer accommodations, wider access to disability insurance and enhanced data collection.

OSHA Wins Workplace Violence Case

Workplace violence is one of the major causes of deaths and injuries for workers — especially in health care. Despite the fact that the hazard — and prevention measures — are well known, employers continue to resisted implementing measures to protect workers and insist that nothing is to be done — just part of the job. An administrative law judge in Denver disagreed with the employer’s “nothing to be done” defense, affirming the findings of an OSHA investigation that determined a Louisville acute inpatient psychiatric treatment facility, Centennial Peaks Hospital, had exposed employees to workplace violence hazards from aggressive patients who regularly assaulted and seriously injured them. The judge found, after a two-week trial that OSHA’s suggested abatement measures were justified. They included:

- Implementing a comprehensive workplace violence prevention program.

- Training employees on the workplace violence prevention plan.

- Providing employees with reliable communication devices, such as radios and/or personal panic alarms.

- Reconfiguring the nurses’ stations to prevent patients from entering easily and assaulting staff within.

- Ensuring that units are staffed adequately to handle aggressive and escalating patients more safely.

- Conducting post-incident debriefings and investigations to improve future responses to situations involving aggressive patients.

The judge also affirmed OSHA’s $10,229 penalty. OSHA Is working on a workplace violence standard, although at the rate they’re working, it may be many years before it’s issued.

Workplace deaths up 40% in south-central Pennsylvania

Workplace fatalities in south-central Pennsylvania have increased 40% so far this fiscal year (which ends September 30), prompting a call Friday from the federal agency that monitors workplace safety. 21 workplace fatalities have been reported across the 14-county south central Pennsylvania region covered by OSHA Harrisburg office since October 2021. There were 15 workplace fatalities during the 2021 fiscal year. The numbers include 5 from COVID-19. Kudos to OSHA’s Harrisburg Area Director Kevin Chambers for taking to the airways to plead with employers to make their workplaces safer. “It’s not the same exact industry with the same exact causal factors involved,” said Chambers. “In fact, there’s been quite a difference between most of them.” Nonetheless, it’s an alarming trend that has the federal agency calling on employers to do more to fulfill their legal responsibility to protect workers. “We’re asking that south central Pennsylvania employers take the time to evaluate their workplace, take a look at their health and safety programs,” explained Chambers. “If they find hazards, fix them. Talk to your employees, see what they’re encountering.”

The deaths are likely undercounted because they are fatalities that OSHA investigates. For example, these figure likely don’t include the recent death of a truck driver near Harrisburg earlier this month because OSHA doesn’t normally investigate vehicle incidents, nor the death of Lebanon City Police Lt. William Lebo because OSHA doesn’t investigate the deaths of police officers, nor are public employees covered by OSHA in Pennsylvania.

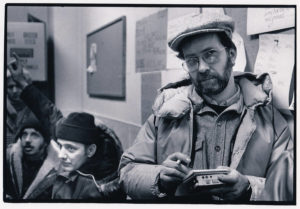

Labor Reporter David Moberg Dies at 78

From almost the first day I moved to Washington DC, In These Times’ David Moberg has been one of my main sources for labor news. In an era where the labor beat has almost disappeared from labor publication, Moberg’s perseverance has stood out. Moberg died last month at age 78. Steve Franklin, one of this country’s few remaining labor reporters, relates in a comprehensive and heart-felt review of Moberg’s career:

His words were guided by a lifetime discipline of providing the long view. As a staff writer for In These Times from its birth in 1976 and later a senior editor, he secured a unique position for himself in the small band of the nation’s labor writers (which until recent years had seemed on the edge of extinction). What made his work stand out was the combination of grounded reporting on people and events with a very clear analysis about where American workers had come from, where they were headed and what more could or should be done on their behalf.

His death on Sunday, July 17, at 78 years old after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease stirred an outpouring of loss and admiration for a somewhat shy, soft-spoken journalist, whose vision ranged from the struggle of Chicago cab drivers to theories about how to make capitalism more just and fair.

“What struck me about David was that he inspired so many of us to fight for labor’s cause without ever raising his voice, without ever overstating his case, without ever going beyond the facts. That’s what made him so persuasive,” says Tom Geoghegan, a labor lawyer-who has written extensively himself about workers and unions. “Like many others, I just trusted every word he wrote. He could have made a fortune as a big-name journalist, but he chose instead to enrich the rest of us. I feel I owe him so much.”

Court Orders Tampa Electric to Implement Safety Changes

Following a guilty plea by Tampa Electric last may in the death of five workers in 2017, a federal court has ordered the company to implement a safety compliance plan audited by an independent third party, pay a $500,000 penalty and be subject to 36 months of probation. Michael McCort, 60, Christopher Irvin, 40; Frank Lee Jones, 55, Antonio Navarrete, 21, and Amando J. Perez, 56 — were killed at Tampa Electric’s Big Bend Power Station after management forced them to do a procedure that the company knew was hazardous.

The workers were killed when they tried to clear hardened coal slag accumulating at the bottom of a 12-story tall boiler without shutting the boiler down first. Thousands of gallons of molten slag gushed from the boiler, shooting out of the tank and covering the workers. Shutting down and restarting a boiler can cost utilities up to a quarter-million dollars. I wrote an extensive analysis of the causes of this tragedy here, with a follow-up here and the Tampa Bay Times investigated the tragedy and has been following the aftermath of the explosion.

Kentucky Candle Company Cited after Tornado that Killed Nine

Kentucky OSHA has issued citations to Mayfield Consumer Products totaling $40,000 against in the death of 9 workers last December when a Category 4 tornado ripped through the plant. KY OSHA issued three citations related to lack of emergency action plans, and four citations related to bloodborne pathogens. Those fines may seem a bit low for the deaths of 9 workers, but they’re more than federal OSHA issued against Amazon after the deaths of 6 workers during the same string of tornadoes. OSHA did not believe it had enough evidence to file a General Duty Clause violation against Amazon, and sent the letter a Hazard Alert Letter instead. In addition, Kentucky is one of the state plan states that has never adopted OSHA’s maximum and minimum penalty increase implemented in 2016. Mayfield is contesting the violation. The company has also announced that it will be closing the factory and permanently laying off half its employees. Mayfield is contesting the KY OSHA citation.

Safety as an Union Organizing Issue

Ask almost any union health and safety staffer to list their biggest frustrations and failure of the union to use health and safety issues in organizing campaigns is likely to appear high on the list. But that is hopefully changing. In a Labor Day article in the Washington Post, veteran labor reporter Steven Greenhouse describes how, over the last year, employees at some of the nation’s best-known companies — Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s, Apple, REI and Chipotle — have organized for the first time. And young people are leading those organizing drives. One of the biggest issues: safety. And specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic:

The pandemic — or the way many employers treated workers during the pandemic — has played an outsize role in the current unionizing surge. Many front-line workers, whether supermarket cashiers, bus drivers, health-care workers, meatpackers or fast-food cooks, risked their lives day after day. They grew furious that their employers were slow to provide them with personal protective equipment — remember the McDonald’s workers who said they were told to use coffee filters and dog diapers to protect themselves? Front-line workers were also angry that their employers did not give them hero or hazard pay — a few extra dollars an hour to reward them for the risks they were taking — while many corporations’ white-collar employees, who earned far more, worked safely from home.

OSHA & USDA Try Again to Cooperate on Worker Safety in Meat Plants.

Thirty-one years ago this week, twenty-five chicken processing workers were killed when fire swept through the Imperial Food Products Company plant in Hamlet, N.C. A grease fire started on a chicken fryer and spread quickly inside the Imperial Foods Products building. Emergency response was delayed because telephones inside the building could not be used. The building’s sprinkler system failed, forcing workers to run through heavy smoke. Workers tried desperately to escape the smoke and flames, clawing at exit doors that had been locked to keep the workers from stealing chickens.

In it’s entire 11 year existence, OSHA had never inspected the plant. But USDA visits poultry plants frequently (and had told the plant to lock exit doors to prevent flies from entering.) Because USDA employees were in the plants frequently, but knew little about worker safety, OSHA and USDA signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 1974, intending to increase cooperation between the agencies, but it was never implemented. Last month, the agencies decided to try again. OSHA and USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) approved another agreement designed to improve the detection of workplace hazards by requiring FSIS inspectors to be trained within 120 days in workplace hazard recognition and in making referrals to OSHA. Will it work better this time? Some OSHA experts are skeptical. Debbie Berkowitz, a former OSHA chief of staff and senior policy adviser during the Obama administration, adding “they had no interest in implementing it. The FSIS is incredibly close to the industry, they are a captured agency.”