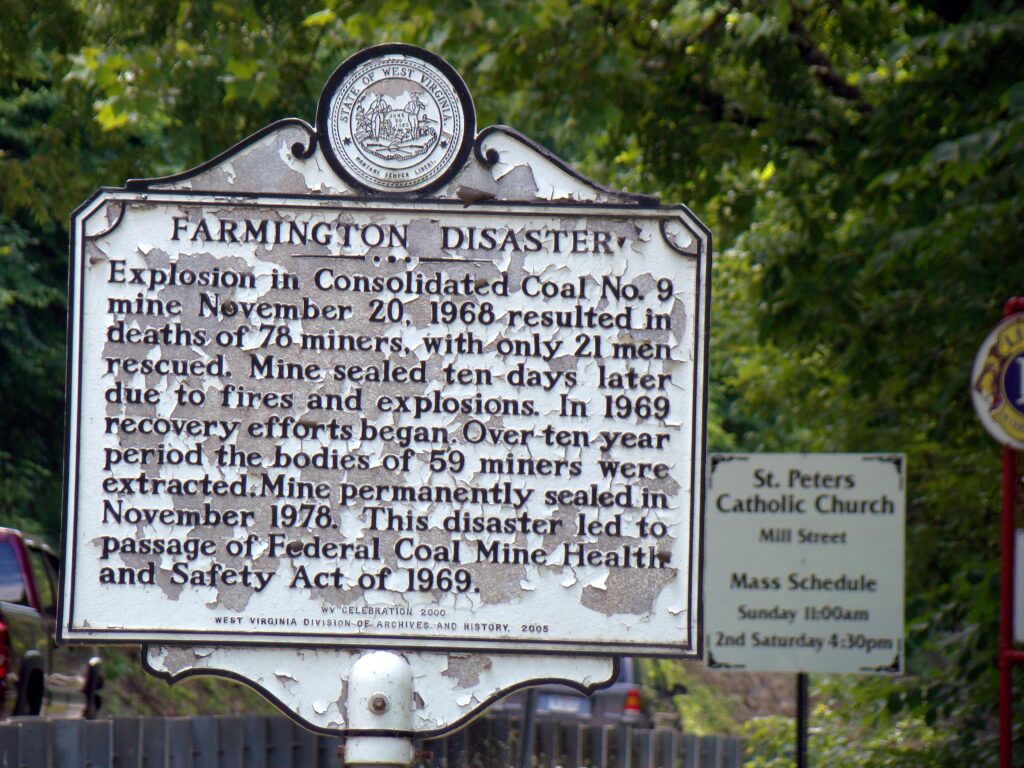

Today is the 57th anniversary of the 1968 Farmington Mine explosion.

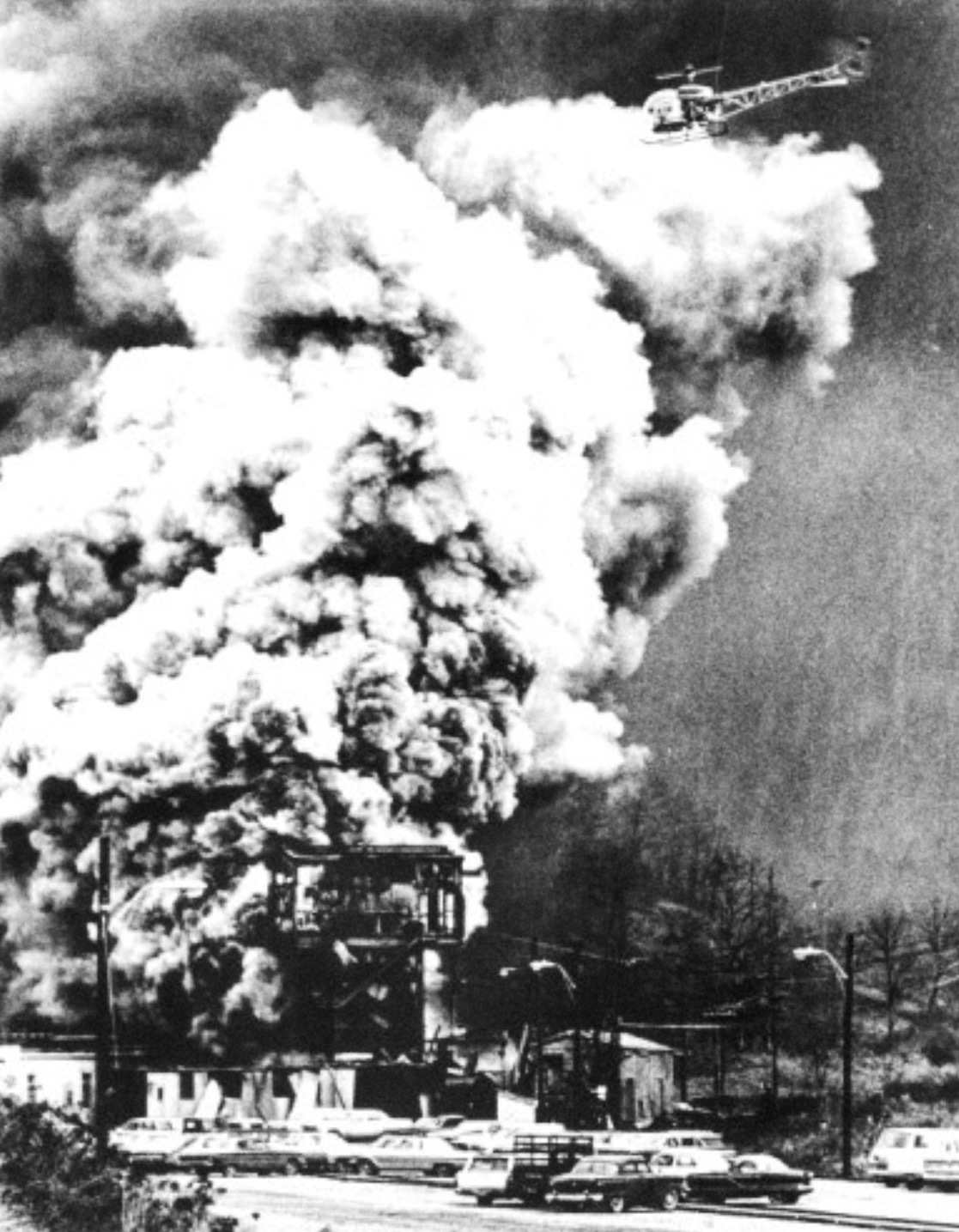

At 5:30 in the morning on November 20th, a huge explosion tore through Consolidation Coal’s Number Nine mine. The force of the blast could be felt for miles. There would be dozens of other explosions in the days to come and intense fires. Ninety-nine miners were underground at the time; 21 managed to make it to the surface, the other 78 all died. Nineteen bodies were never recovered.

The remains of 19 remained in the shaft, which would be sealed off 10 days later with no input from miners’ families.

Farmington was the first major mine disaster to be televised and the tragedy rocked the nation — with implications that reached far beyond the families, friends and co-workers of the 78 lost miners.

The disaster also had a major impact on the United Mine Workers of America. Following the retirement of legendary UMWA President John L. Lewis, the union was taken over by Tony Boyle, a corrupt former assistant to Lewis. Miners were increasingly dissatisfied with Boyle, largely because he opposed efforts to improve the safety conditions of coal miners, or to fight for protections for increasing numbers of members who were suffering from Black Lung disease.

2000 miners marched on the West Virginia State Capitol to demand recognition of black lung disease. Eight days before, on February 18th, the mines in the southern West Virginia coalfields emptied as miners walked off the job. This “wildcat” strike was not authorized or endorsed by the miners’ union, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). However, in the months leading up to these events, a growing number of West Virginia miners had grown dissatisfied with UMWA leadership.

The tipping point for the UMWA and Boyle came after the Farmington explosion when mine operators sent a plane to Washington to bring union head Tony Boyle to the mine. Boyle was cozy with mine operators and after arriving at the mine, Boyle called the disaster “an unfortunate accident.”

He went on to praise the company’s safety record: “As long as we mine coal, there is always this inherent danger. This happens to be one of the better companies, as far as cooperation with our union and safety is concerned.’’ And then he refused to meet with the miners’ widows.

Boyle controlled the entire election apparatus and “won” the election. When Yablonski presented evidence to the U.S. Department of Labor that Boyle had stolen the election, Boyle ordered his assassination. On New Year’s Eve 1969, Yablonski, his wife, and his 25-year-old daughter were murdered.

The Murder of Jock Yablonski

Boyle’s closeness to the mine operators, his refusal to fight for black lung protections and finally his tepid response to the Farmington disaster convinced Boyle enemy and former UMW official Joseph “Jock” Yablonski to run for President against Boyle on a reform platform. Yablonski was a former miner and had been President of UMW District 5 before Boyle fired him several years before the Farmington explosion.

Boyle controlled the entire election apparatus and “won” the election, but when Yablonski presented evidence to the U.S. Department of Labor that Boyle had stolen the election, Boyle ordered his assassination. On New Year’s Eve 1969, Yablonski, his wife, and his 25-year-old daughter were murdered, fatally shot to death at home by three gunmen found to have been hired on orders of Tony Boyle. Boyle eventually receive three life sentences and died in prison.

The Department of Labor ordered the union to re-run the election under federal supervision. The reformers won the second election, selecting Arnold Miller to head the union.

If you’re interested in Yablonski’ s fight and miners fight for safe workplaces during this period, check out a new podcast series, “Shadow Kingdom, Coal Survivor,” which details the months leading to Yablonski’s murder and the aftermath.

The Blood of Coal Miners

Fortunately, with enough organizing, good things can sometimes come out of disasters, as veteran mine safety attorney Tony Oppegard wrote two years ago in Confined Space. I am reposting Tony’s essay here:

I was a freshman in college on November 20, 1968 when a gigantic methane explosion destroyed Consolidation Coal Company’s No. 9 mine – located near Farmington and Mannington, West Virginia – killing 78 coal miners. The bodies of 19 of those miners are still entombed in the mine today.

It is said that all mine safety laws are written with the blood of coal miners, and that certainly was the case with the Federal Coal Mine Health & Safety Act of 1969, which was enacted by the U.S. Congress in response to the Farmington Mine Disaster. It was the first comprehensive mine safety law ever enacted in America.

It is said that all mine safety laws are written with the blood of coal miners, and that certainly was the case with the Federal Coal Mine Health & Safety Act of 1969

That law (called the “Coal Act”), along with its successor, the Federal Mine Safety & Health Act of 1977 (“the Mine Act”) – which was enacted in response to the Scotia Disaster in Letcher County, Kentucky, on March 9 & 11, 1976 (26 killed) – have literally saved the lives of thousands of American miners in the past 5 1/2 decades. But having represented the families of miners killed because of unsafe conditions, I can attest to the never-ending pain that such disasters cause.

Not surprisingly, the American coal industry opposed both of these life-saving mine safety laws, as well as the passage of every other meaningful mine safety regulation that has been enacted in the past 55 years. The coal industry has labeled itself as the “Friends of Coal” for political purposes, but it only cares about miners so long as they do exactly what they are told to do and don’t complain about unsafe or unhealthy working conditions.

When miners insist on a safe and healthy workplace, they are frequently fired for their efforts, which is why I – with my colleague Wes Addington of the Appalachian Citizens’ Law center – am still filing safety discrimination cases on behalf of miners who have been discharged or otherwise discriminated against because of making safety complaints or refusing to work in unsafe conditions. In that regard, very little has changed in the mining industry…

And a later example: On January 6, 2006, an explosion at the Sago mine in West Virginia killed 12 miners who were trapped an suffocated in the mine without adequate respiratory protection or the ability to communicate to the surface. The fate of the miners made national headlines for days. Less than six months later, Congress passed and President Bush signed the MINER Act which corrected many of the problems that doomed the Sago miners.

Fast Forward: War on Miners

Today we see the Trump administration attempting to discard the lessons of the past and reverse the safety and health gains that coal miners have fought and died for over the past bloody decades. Trump has said he wants to expand the use of coal in this country, and declared war on the alleged “War on Coal.” But instead of killing the war on coal, Trump has declared war on coal miners: dismantling NIOSH which provides surveillance and medical support for miners suffering from black lung. He has also eliminated the parts of NIOSH that work to improve mine safety, proposed to eliminate almost the entire NIOSH budget, and refuses to enforce MSHA’s silica standard that was issued in 2024 to reduce the growing rates of severe black lung that has been hitting younger miners.

Twenty-nine coal and metal/non-metal miners have been killed on the job this year according to MSHA — four in the last month — compared with 28 all of last year. West Virginia has the most mine fatalities this year with five. Texas is next with four, followed by three in Missouri, two in California and two in Pennsylvania . Thirteen states have one mine fatality in 2025, including Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota and Tennessee.

The UMW was once powerful enough to shut down the nation, but those days are long gone. Nevertheless, their efforts, along with the efforts of worker safety and public health advocates across the country are fighting back against the Trump administration’s war on coal miners — with some limited success. Court decisions have forced the Administration to restore some of NIOSH’s services, and Congress, embarrassed by Trump’s attack on the nation’s coal miners is proposing to increase (the House) or at least flat fund (the Senate) NIOSH in defiance of the White House proposal.

But major budget and court battles — and eventually the 2026 mid-terms — still lie before us. Behave as though the lives of America’s coal miners depend on the outcome of those fights. Because they do.

Jordan:

Nice, and timely piece of work. Thanks very much.

JimWeeks