Yesterday, Secretary of Labor Alex Acosta announced that Ronald Reagan would be named to the Labor Hall of Honor. To put this nauseating action in some kind of perspective, below is a long (sorry) post I published on June 15, 2004 in the first incarnation of Confined Space, shortly after Reagan’s death. Because of its age, many of the links will no longer work.

Reagan was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that.

According to the “official” hagiography, Ronald Reagan had single-handedly defeated the Soviet Union and ended the Cold War. And in his spare time he revitalized the American economy by cutting taxes and ending the era of big government whose regulations were slowly strangling the free market, free will and liberty itself. And he did it all with great humor and affability.

Of course, one’s definition of “liberty” and “freedom” may differ depending on whether you are interested in freedom to run your business as you want, or freedom to enjoy safe working conditions and to come home from work alive. Ronald Reagan and his followers clearly defined liberty differently than most working people and it was his version of liberty that led to the Reagan regulatory reform policies that effectively took away the right of American workers to work in a safe workplace.

William Greider observes in the current Nation remembers that “a chilling meanness lurked at the core of Reagan’s political agenda (always effectively concealed by the affability), and he used this meanness like a razor blade to advance his main purpose–delegitimizing the federal government.”

According to Steven Malloy of the Cato Institute:

Getting a grip on runaway federal regulation was one of Ronald Reagan’s many significant achievements as president. But, media tributes since his death have scarcely mentioned President Reagan’s efforts at regulatory reform.

Former Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers (OCAW) attorney and staff representative Steve Wodka agrees that this part Reagan’s legacy has been neglected, although he differs somewhat on the “significance” of Reagan’s “achievement:”

Ronald Reagan and his administration cost hundreds of thousands of workers to needlessly suffer death and injuries on the job and shortened their lives from preventable occupational diseases. His direct attack on workers by firing the air controllers is well-known. His destruction of OSHA and the set backs that he caused in the field of worker health and safety are hardly known beyond our immediate group.

His view of OSHA was summed up in a piece that he wrote for the Conservative Digest in October, 1975: “‘OSHA’ is a four-letter word that’s giving businessmen fits.”

OK, then, lets look at Reagan’s “achievements”.

First, you should understand that this is my history of the Ronald Reagan years at OSHA — with a bit of help from my friends. If you want the official history, you can read the fifth (and final) chapter of the Department of Labor’s official history of OSHA entitled: Thorne Auchter Administration, 1981-1984: “Oh, what a (regulatory) relief” (The entire official DOL history of OSHA’s first twelve years can be found here.)

Second, there is far more that can be said about the effect of Ronald Reagan on the American workplace than I can write here. If you want to contribute to this story, make free use of the “Comments” link at the end, or I’d be glad to publish any longer pieces as separate articles.

***

The newly elected administration of Ronald Reagan lost no time in putting its imprint on OSHA. Wodka remembers that:

Within 9 days of taking office, on January 29, 1981, Reagan froze all federal regulations that had not become effective.

On February 10, 1981, the U. S. Chamber of Commerce submitted a list of 10 OSHA rulemakings to Reagan’s Task Force on Regulatory Reform which should be “prevented,” including a proposal to reduce the permissible limit for asbestos exposure. Eleven days later, Reagan’s Budget Director, David Stockman, announced that the proposed asbestos rulemaking would be rescinded.

According to the official DOL history:

These included proposals to amend the hearing regulations and the cancer policy and to require the labeling of hazardous substances (the “right-to-know” proposal). To begin implementing the longer term aspects of Regulatory Relief, Auchter quickly appointed special “task groups” to study existing rules on lead, cotton dust and noise and to develop a new labeling proposal.

Instead of looking for someone to head OSHA who actually had a background in health and safety, Reagan chose construction executive Thorne Auchter. According to the official history:

In February 1981 President Reagan announced that he would nominate Thorne G. Auchter for that post. Auchter was the 35-year-old executive vice president of Auchter Co., a family-owned construction firm based in Jacksonville, Florida. He had served in President Reagan’s 1980 election campaign as special events director for Florida.

Former OSHA scientist Peter Infante was present at the creation of the Reagan/Auchter administration and quickly became the symbol for Auchter of all that was wrong with OSHA, leading to an attempt for fire him for insubordination. As Infante remembers it:

The early Reagan administration (Auchter) also embargoed the joint OSHA/NIOSH Current Intelligence Bulletin on formaldehyde that had been signed by the head of OSHA and NIOSH at the end of the Carter Administration. The Formaldehyde Institute did not want information about the cancer causing properties of formaldehyde released.

The Reagan Administration also proposed to fire me for writing to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (on Agency letterhead) that its review of formaldehyde incorrectly concluded that there was “limited evidence” in experimental animals that formaldehyde caused cancer. OSHA and NIOSH had already concluded there was sufficient evidence of cancer and hence were about to publish the Health Information Bulletin (HIB) on formaldehyde at the end of the Carter Administration.

At the time the Deputy Dir of OSHA (Mark Cowan, who joined the Agency from the CIA) met with John Byington of the Formaldehyde Institute and they then concluded that the experimental evidence for formaldehyde to cause cancer in animals was “flawed.” Albert Gore, then in the House, held 2 days of oversight hearings on OSHA’s firing me. A month after the hearings, the Agency said it could not find any evidence that I was “insubordinate” or that I “misrepresented” the Agency’s scientific position on formaldehyde. Thus, the charges against me were dropped.

Months later, the agency was told it could not withhold the distribution of the HIB since the government had paid for the printing of it.

It also probably did not help OSHA’s case that they attached the letter from the Formaldehyde Institute complaining about Infante to the letter of dismissal.

One of Auchter’s first actions was straight out of Fahrenheit 451 (Ray Bradbury’s classic named after the temperature at which a book will burn.) The Reagan administration began the day before the recently issued Cotton Dust standard was heard at the Supreme Court. For the business community, the cotton dust standard was symbolic of all that was wrong with Eula Bingham’s OSHA, and government regulation in general.

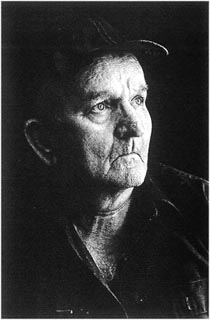

A week after his arrival, Auchter was shocked to find that the cover of an OSHA publication on Cotton Dust displayed a photograph by Earl Dotter of a cotton dust victim, Louis Harrell. Auchter, believing the cover to be inflammatory, ordered the remaining publications destroyed and reissued the document with no photo on the cover.

|

| Louis Harrell |

The “official” DOL history has a slightly different take on the story:

When he [Auchter] learned that the agency was about to publish separate booklets on the cotton dust hazard – one version for workers and another for employers – he temporarily withdrew them because he felt that having separate booklets was divisive. Five days later, a unified booklet was released that contained essentially the same information, but in the meantime organized labor leveled a barrage of criticism at Auchter – the first of many – over the withdrawal.

Auchter also tried to repeal the hierarchy of controls which states that respirators (and other personal protective equipment) should be the last strategy and engineering controls the first. Infante recalls that:

Auchter was in favor of putting workers in respirators instead of lowering PELs for substances that standards were being developed for like EtO, arsenic, certain sectors for the cotton dust standard, benzene, cadmium, etc. We in Health Standards along with the Solicitor of Labor’s office had to argue with him that the OSHA Act required engineering controls for the first line of defense against toxic substances in the workplace.

Medical removal protection triggers for blood lead levels in the lead standard were another target of the Reagan administration. OSHA wanted workers’ blood lead levels to fall to a certain level before the workers were allowed back in the workplace, but the lead industry claimed that levels would never fall that low. In a tribute to their creativity, the industry further claimed that keeping these veteran workers off the job would create safety hazards because they were the most knowledgeable about workplace safety.

Ethylene Oxide was one of the first new standards that Reagan’s OSHA worked on:

In April 1983 Ethylene Oxide (ETO) became the first chemical since 1978 for which OSHA proposed to lower allowable exposure levels. ETO is a gas used primarily as a sterilizer in hospitals and was one of the substances regulated in OSHA’s old consensus standards. In August 1981 the Health Research Group and several unions petitioned OSHA to set an emergency standard for ETO to protect an estimated 100,000 workers in hospitals and elsewhere from possible damage to chromosomes. When OSHA refused their petition, they sued in a federal court.

The court eventually ordered OSHA to issue a standard within one year.

According to the DOL history, Peter Infante again played the troublemaker:

OSHA decided whether or not to set a ceiling for short-duration exposures [Short Term Exposure Limit or STEL] after a brief “memo war” between Peter Infante, who thought a short-term level was needed, and Leonard Vance, who did not. Infante lost and the short-duration maximum was omitted from the proposal, much to organized labor’s disappointment. Hearings were held in July 1983.

The official history doesn’t finish the story, however. When it came time to write the final standard, the public comments on the proposal and testimony at the public hearing so overwhelmingly proved the need for a STEL, that OSHA included it in the “final” version sent to OMB as the court-ordered deadline approached. OMB was not amused and, at the last minute, ordered OSHA to remove the STEL along with any justification in the preamble. Facing a deadline only hours away and not looking forward to contempt-of-court charges, the staff was ordered to take a marker and literally cross through any reference to the STEL. The inexpertly crossed-through document was then delivered to the Federal Register, to be retrieved later as part of a successful court challenge to the rule.

But, that’s still not the end of the story. Months later, a House committee hauled OSHA to a hearing studying the development of the standard and the missing STEL. Accusations were made that Director of Health Standards, R. Leonard Vance, had met illegally with representatives of the Ethylene Oxide Industry Council.

Vance denied the charge and was asked to produce his calendar. He consented, but later was reluctantly forced to inform Congress that he had taken his records on a hunting trip and his dogs, after apparently feasting on bad bunny rabbit, vomited on them, forcing him to discard the putrid records before they could be delivered to Congress.

I hate it when that happens.

The Standards Process

As the Washington Post’s Cindy Skrzycki puts it.

Though the Reagan administration is remembered most vividly for cutting agency budgets, eliminating rules and creating a task force to scrutinize regulations that the administration and business wanted to change, regulatory experts say the real effect of those years can be traced to a change in the process of creating rules.

Within weeks of taking office in 1981, the Reagan administration issued an executive order that, for the first time, set up a system of reviewing all of the rules issued by dozens of federal agencies. The Feb. 17 order set out a protocol of review and cost-and-benefit analysis that laid the groundwork for the way that the federal regulatory system works today. It replaced a much looser system of consultation where previous administrations reviewed some but not all rules.

The result was a kind of deregulation that did not depend so much on removing regulatory barriers for entire industries, as the Carter administration did for airlines in 1978. Instead, it used administrative tools that sometimes made it harder for federal agencies to issue rules as their regulatory agendas became subject to strict oversight by the White House.

AFL-CIO Occupational Health and Safety Director Peg Seminario recalls how the burden on OSHA has grown over the years.

In the early 1970’s, it took about six months to two years for the agency to develop and issue major rules such as those on asbestos and vinyl chloride even though these rules were controversial and contentious. The preambles for the standards were only five to ten pages, but the standards, evidence and material were upheld by reviewing courts.

In the mid- to late-1970’s, the process was somewhat longer, taking three years for the promulgation of the lead standard, four years for standards on cotton dust and arsenic, all major regulatory initiatives. But during that time the agency developed and issued numerous other standards including those as benzene, acrylonitrile, DBCP, cancer policy, access to exposure and medical records, hearing conservation, fire protection, and guarding of roof perimeters.

In the early 1980’s, as a result of the anti-regulatory philosophy of the Reagan Administration, the time for standards development and issuance became even longer as action was only taken in response to Congressional mandates or court orders. For example, it took six years and a lawsuit for OSHA to issue its formaldehyde standard and five years and a Congressional mandate for the issuance of the blood borne pathogens standard.

Other standards initiated during the Reagan Administration took much longer. Standards on 1,3 butadiene, methylene chloride and respiratory protection each took 12 years from start to finish and were not completed until the Clinton Administration.

Most recently, we saw a situation where it took OSHA more than ten years to issue an Ergonomics standard. The regulatory language spanned a total of 8 pages in the Federal Register, while the “Preamble,” containing extensive economic and regulatory analyses, went on for an additional 600 pages. Following issuance of the standard, industry association representatives inflamed their members with the specter of 600 page standard! The tragic irony is that the 600 page preamble that raised the ire of the Republicans and business community was largely a result of Republican and business community-inspired legislation and Executive Orders endlessly increasing the amount of analysis required to justify a standard.

Reagan’s OSHA Budget

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), founded in 1970, saw its budget increase steadily from 1975 to 1981, and its staffing–the key to enforcement–rise from 1975 to 1980. But, during the Reagan years, it lost funding and people. Its staffing went from 2,951 in 1980 to 2,211 in 1987. Clinton increased spending on OSHA in the 1994 and 1995 fiscal-year budgets, but in fiscal year 1996, the Republican Congress forced the administration to agree to budget cuts and another reduction in staff. In the past two years, the administration has finally got the budget back up, but there are still fewer people working at OSHA in 2000 than there were in 1975, even as OSHA’s job has become more complex and demanding.

Enforcement

One of the goals of former construction industry executive Thorne Auchter was “the eradication of the “prevailing adversary spirit” among labor, management and government.” All of those inspections were clearly “adversarial,” especially for employers already doing the right thing. How to tell the “good” employers from the “bad?” Just check their injury and illness records before deciding whether to inspect. UNITE’s Eric Frumin recalls Auchter’s infamous “record check” inspections and the tragic consequences:

In July, 1981, OSHA Director Thorne Auchter, with the help of his new deputy Assistant Secretary of Labor Mark Cowan told his Regional Administrators that effective October 1, they would impose a new category of inspections on their inspectors — the infamous “records-check” inspection – -which required inspectors to stop from entering the workplace if the plant’s OSHA Log showed a below-average injury rate. Two years later, at the Film Recovery Corp. plant in Elk Grove, IL, an inspector did exactly that, and weeks later a worker died from arsenic poisoning. The Cook County Coroner ruled it a homicide because of the employer’s blatant efforts to hide the arsenic hazard he spray-painted over the skull-and-crossbones warnings on the labels of hazardous chemicals). The Cook County State’s Attorney (Richard Daley Jr.) prosecuted the first homicide case for a workplace fatality. The record check policy was finally reversed a couple of years later, as Bush I began to run for re-election and the scandal of cooked injury books was revealed in the Union Carbide inspection in W. VA. Thousands of inspections were wasted in the interim. So much for effective government.

A number of other actions taken by Auchter weakened OSHA’s enforcement ability, according to the DOL history:

Inspectors began to cite fewer “serious” violations and greatly reduced the size of penalties assessed. OSHA instituted a new system for exempting firms with good safety records from safety inspections and targeting those with poor records. “General Duty” clause citations were restricted and the requirement for walkaround pay was dropped.

The walkaround pay repeal was particularly hard-hitting for workers. The OSHAct gives workers the right to “walk around” the workplace with OSHA inspectors. Until Reagan, this “walkaround right” was presumed to imply that workers should also be paid for the time spent walking around with the OSHA inspector. Reagan and Auchter took that right away. Workers still had the right to walk around, but no longer had the right to be paid for the time spent exercising that right.

One of main worker safety debates raging today is whether or how to get OSHA to pursue more criminal prosecutions and jail time against employers whose willful violation of the law causes the death or serious injury of a worker. According to NY Times investigative reporter David Barstow, much of OSHA’s refusal to pursue more criminal prosecutions can be traced back to the administration of Ronald Reagan:

When people at OSHA explain their reluctance to pursue criminal prosecutions, they sometimes begin by pointing to the example of Ronald J. McCann.

Mr. McCann, acting regional administrator in Chicago during the early 1980’s, was an early champion of criminal prosecutions. He had a simple, no-nonsense approach: If a death resulted from a willful violation, it should be referred to the Justice Department without delay.

But in the early days of the Reagan administration, he said in a recent interview, that policy brought a clear rebuke from OSHA’s new political appointees. Twelve times he sought prosecutions. “They were all thrown out.” Soon after, he said, he was removed from his job and transferred so often that he ended up living in a tent to avoid moving his family again.

“We wanted to stop people from killing,” said Mr. McCann, now retired. “We wanted to make an example of those few people who do so much harm to society for their own personal gain.”

But Reagan’s biggest impact on OSHA may have come from an action that wasn’t directly targeted at OSHA at all — the firing of the PATCO strikers. OSHA was only created, and only survives today (such as it is) due to the influence of the American labor movement — both directly through lobbying OSHA, Congress or the President — and indirectly, through electing worker-friendly politicians. By declaring war on PATCO and the entire labor movement, Reagan gave the green light to American business to declare war on workers and unions. We’re still feeling the effects of that war today in the form of a weaker labor movement, unending attacks on workers’ rights, compensation and benefits, and a weaker OSHA.

Other Actions

Research: Some actions had longer term implications as AFT’s Darryl Alexander points out

One of the most chilling things was the suppression of Department of Health and Human Services research on healthcare, disease and the health status of the population. The administration wouldn’t release data and literally stopped collecting information on important indicators. The postulate: No data; no problem. Seems like a tradition that is followed today.

Training Grants: One of the most significant accomplishments of Eula Bingham’s administration at OSHA was the development of “New Directions” training grants. Money was provided to unions, COSH groups, universities and other non-profit organizations, generally for a period of five years, to develop a self-sustaining program to provide training and develop training materials for workers. During Bingham’s administration, OSHA funding reached almost $14 million (in addition to several million provided by the National Cancer Institute.) In Reagan’s first budget, the funding for the worker training grants was cut in half, while funding for “consultation programs” was increased. Worker training funding did not regain its previous funding levels until midway through the Clinton administration, over 15 years later. (Currently, the Bush administration is again attempting to slash funding for worker training programs.)

Voluntary Protection Program: Consistent with his desire to increase “voluntary” actions by employers, Auchter created the Voluntary Protection Program which offered employers with exemplary safety programs freedom from general schedule inspections. Although employees could still file complaints and request inspections, critics objected to the exemption from general inspections and the resources that the new program would require. Since then, the number and variety OSHA’s voluntary programs have mushroomed, sucking up an increasing portion of OSHA’s limited resources.

Conclusion

Peter Infante reminds me of a rather Freudian “typo” in the Federal Register containing the final Ethylene Oxide standard:

If you can find a 1982 Code of Federal Regulations, a footnote indicates that the toxic level for ethylene oxide in the workplace was “1 Ronald Reagan.” This typo was appropriate.

Today, even more than in the 1980’s, American workers are feeling the effects of that anti-regulatory atmosphere that Ronald Reagan did so much to promote. Only today, the situation is worse because the anti-government, anti-worker zealots have learned to be much more subtle when they undermine worker protections. As bad as the Reagan years were, career civil servants claim that the current Bush administration is much worse.

Indeed, Ronald Reagan’s “regulatory reform,” based on his interpretation of “liberty” as the freedom for employers to do what they want, when they want, to whom they want, doomed countless working people to preventable injury, illness and death. He may have done it with style and with a smile, but the damage was the same. That is the real legacy of Ronald Reagan.

Finally, although this article focuses solely on OSHA, I can’t end it without providing some assistance to those of you trying to steer through rhetorical trash strewn about the land by the media over the past couple of weeks. This is from Atrios:

Russert last night on Larry King:

RUSSERT: One other political point: The Republicans achieved control of the United States Congress for the first time in 70 years, of both houses, under Ronald Reagan.

Look, I’m fine with the Peggy Noonan footworshipping. I’m fine with all the “Reagan destroyed the Soviet Union singlehandedly” nonsense. I’m fine with all of these types of things because they’re opinions. Some are silly opinions, and there should be some balance to them, but they are still opinions.

What I’m not fine with is all the factual errors that creep into the coverage by supposedly “unbiased” reporters. Such as…

- The House and Senate did not both come under Republican rule during Reagan’s time.

- The Berlin Wall did not come down when Reagan was in office.

- Reagan is not the president who left office with the highest approval rating in modern times.

- Reagan was not “the most popular president ever.”

- Reagan did not preside over the longest economic expansion in history.

- Reagan did not shrink the size of government.

- Reagan did preside over what was at the time the “biggest tax cut in history” but it was almost instantly followed up by the “biggest tax increase in history.”

- Reagan was not “beloved by all.” He was loved by some, liked by some, and hated by some with good reason.

Those concerned about the safety and health of Americans who go to work every day believing in their freedom to come home alive and healthy have good reason to hate Ronald Reagan.

As an inside-the-buiding witness to what was going on at OSHA’s national office in those Reagan years, I can say that all you’ve set out above is certainly accurate. It was horrifying to observe the retribution being dealt out to employees like Pete Infante and Ron McCann, simply for doing their jobs. There were others who suffered as well, who were decidedly committed to the principles embodied within the OSH Act. Guys like Gabe Gillotti (Regional Administrator at San Francisco) and Nick DiArchangel (Deputy Regional Administrator at New York) were similarly persecuted for the “offenses” in a like manner.

Notwithstanding, there was some great humor that administration’s OSHA-appointees provided as well. Auchter’s blond “Angels”; The proliferation of elephant statuettes of all sizes cluttering Mark Cowan’s office; the arrest of Joe (Scooter) Scudero (football player turned Labor Liaison) for impersonating a peace officer…., All these things (and more) gave proof to the (low) priority Reagan’s White House attached to workplace safety & health.

Sadly, the pendulum continues to swing wildly from administration to administration since. Worker’s would be much better off if that pendulum was more stable…….