Cheer up. It’s not all bad news out there.

OSHA, and the workers it helps to protect, won the lottery– for now: The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals three judge panel, randomly chosen to hear the case about whether or not to lift the stay of OSHA’s Vax-or-Test Emergency Temporary Standard, includes two judges who had actually studied the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHAct) and related legal precedents, read the OSHA COVID-10 standard and its explanatory preamble, and understood the crisis that workers in this country continue to face.

Accordingly, on Friday evening, in a 2-1 decision, the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, noting that the COVID-19 pandemic has “wreaked havoc across America,” lifted the stay on the OSHA standard that was imposed by the 5th Circuit the day after OSHA issued the standard. The requirements of the standard will move forward, with a month delay — at least until the 6th Circuit renders a decision on the full merits of the standard and the Supreme Court has its say.

After the misinformation-laden political screed blocking the standard that was issued by the 5th Circuit last month, the 6th Circuit’s decision was a breath of fresh air, logic and recognition of real-world facts and law.

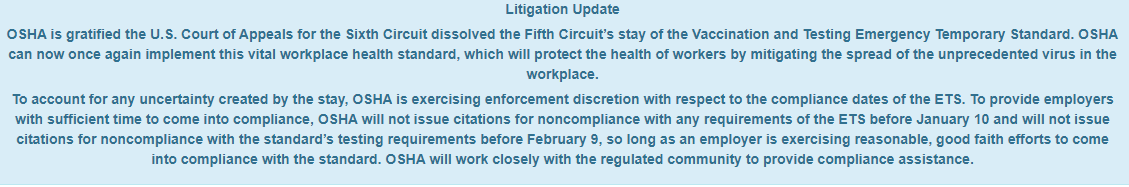

New Compliance Deadlines

OSHA responded to the Court’s decision by setting new deadlines for compliance. All of the requirements of the standard, except for vaccinations (or weekly testing), must be complied with by January 10. By February 9, any workers who are not fully vaccinated must be tested on a weekly basis. No citations will be issued before February 9, “so long as the employer is exercising reasonable, good faith efforts to come into compliance.” Such “enforcement discretion” is not uncommon for OSHA in the early days of a new standard.

The decision came a few days after the court declined to hear the case “en banc” — e.g. by the entire 6th Circuit. Judge Jane Stranch, an Obama appointee, wrote the majority decision. She was accompanied by Judge Julia Gibbons who was appointed by George W. Bush. Judge Joan Larsen, appointed by Donald Trump, dissented.

The Confined Space Analysis

The panel rejected all of the 5th Circuit justifications and arguments of the business-religious coalition that opposed the standard. As I described the 5th Circuit’s decision last month:

The 22-page court [5th Circuit] ruling was an angry political screed that bought into the notion that businesses would suffer “irreparable harm” and be “irreparably injured” by the OSHA standard. Judge Kurt Engelhardt, who penned the decision, called the standard “staggeringly overbroad,” but also underinclusive, and accused OSHA of forcing workers to chose between “their jobs and their jabs.”

It called the standard a one-size-fits-all sledgehammer, questioned OSHA’s authority to issue health standards, mislabeled the standard a “vaccine mandate” and accused OSHA of causing “workplace strife” and “untold economic upheaval” — even before it was issued.

Let’s look at how the 6th Circuit addressed some of the same issues that we discussed after they blocked the OSHA standard last month, as well as some other issues that the Supreme Court will likely consider.

And again, read this with the knowledge that although I know a lot about the Occupational Safety and Health Act and how OSHA operates, I am not a lawyer. But it is clear, even to non-lawyers that the 6th Circuit took a dim view of the legal reasoning displayed by their fellow Court in Louisiana: “Without addressing any of OSHA’s factual explanations or its supporting scientific evidence concerning harm, the Fifth Circuit summarily concluded that ‘a stay will do OSHA no harm whatsoever’ and ‘a stay is firmly in the public interest.'”

What is Needed to Issue an Emergency Temporary Standard?

The language in the Occupational Safety and Health Act is short, simple and rarely used:

6(c)(1) The Secretary shall provide, without regard to the requirements of chapter 5, title 5, Unites States Code, for an emergency temporary standard to take immediate effect upon publication in the Federal Register if he determines —

(A) that employees are exposed to grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful or from new hazards, and

(B) that such emergency standard is necessary to protect employees from such danger.

Are Infectious Diseases “Physically Harmful Agents” Covered by OSHA?

Opponents of the standard, as well as the 5th Circuit, argued that the infectious diseases are not “physically harmful agents” and were therefore not covered by the OSHAct.

According to the 6th Circuit — as well as anyone who knows history and current events — it couldn’t be more obvious that infectious diseases like COVID-19 (and all infectious diseases that present hazards to workers) are “physically harmful agents” — and that they are covered by the OSHAct. Judge Stranch pointed out that OSHA has covered infectious diseases since issuing its 1991 bloodborne pathogens standard (that protects workers from HIV and hepatitis B), and also noted that Congress itself recognized OSHA’s ability to regulated infectious diseases when it passed legislation in 1990 forcing OSHA to finalize the bloodborne pathogens standard. More recently, Congress provided funding to OSHA in the American Rescue Plan “to carry out COVID-19 related worker protection activities.” Obviously, Congress believes that infectious diseases fall squarely in OSHA’s wheelhouse.

The 5th Circuit also argued that because infectious diseases were “widely present in society,” and not just in the workplace, they couldn’t be covered by OSHA. The 6th Circuit disagreed, arguing that OSHA clearly has the authority to regulate hazards that are not “unique to the workplace,” as evidenced by OSHA regulations covering noise — as well as bloodborne pathogens.

Those opposing the standard also maintain that regulating COVID-19 and requiring vaccinations or testing is an unconstitutional expansion of OSHA’s authority that Congress did not intend when passing the OSHAct in 1970. Again, the Court disagreed, arguing that “OSHA’s issuance of the ETS is not a “transformative expansion of its regulatory power.” Indeed, Judge Stranch wrote, “The ETS is not a novel expansion of OSHA’s power; it is an existing application of authority to a novel and dangerous worldwide pandemic.”

Does the OSHA Standard Cause Businesses or Covered Worker “Irreparable Harm”?

Showing that an OSHA standard causes “irreparable harm” to workers or businesses is one criteria a court can use to block a standard. The 5th Circuit had agreed with the businesses suing OSHA that the standard would cause irreparable harm due to the costs of monitoring workers’ vaccinations and test, employees who resign or fired, and (mythical) “stiff” OSHA financial penalties.

But the 6th Circuit found, accurately, that OSHA’s economic analysis established convincingly that the standard was economically feasible — “the costs it imposes do not ‘threaten massive dislocation to, or imperil the existence of, the industry.’”

In fact, Judge Stranch noted, OSHA had likely underestimated the benefits of this standard because the agency’s economic analysis “does not consider the economic harm a business will undergo if it is closed by a COVID-19 outbreak in its workplace.”

Stranch also pointed out that the standard did not cause irreparable harm, because it is not actually a “vaccine mandate.” Businesses can choose the mask and test option, or file for a variance, the standard clearly .

And in one of the strongest statements in the 6th Circuit decision, Stranch wrote:

By contrast, the costs of delaying implementation of the ETS are comparatively high. Fundamentally, the ETS is an important step in curtailing the transmission of a deadly virus that has killed over 800,000 people in the United States, brought our healthcare system to its knees, forced businesses to shut down for months on end, and cost hundreds of thousands of workers their jobs. In a conservative estimate, OSHA finds that the ETS will “save over 6,500 worker lives and prevent over 250,000 hospitalizations” in just six months.

Can Only the States Regulate Public Health?

Opponents of the standard also argue that OSHA was violating the “Commerce Clause” because the ETS regulates public health, which is a “non-economic activity” and the Constitution leaves the regulation of non-economic activity to the states. (The Commerce Clause refers to Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the power “to regulate commerce … among the several states.)b

But the 6th Circuit judges ruled that the 5th Circuit was wrong to decide that OSHA was attempting to regulate in an area reserved to the states, because “Hazards are often regulated by both OSHA and state agencies, such as exposure to lead. But overlap does not limit the authority Congress granted to OSHA to regulate the same risk. The basic reason for the OSHAct was that Congress determined that “illnesses arising out of work situations impose a substantial burden upon, and are a hindrance to, interstate commerce in terms of lost production, wage loss, medical expenses, and disability compensation payments.” In fact, “Congress, in adopting the OSH Act, decided that the federal government would take the lead in regulating the field of occupational health.” And finally, in the OSHAct, Congress gave OSHA the authority to preempt state and local standards that conflict with OSHA standards.

Is COVID-19 A Real Emergency?

A court can block a standard if it predicts that the agency is unlikely to “succeed on the merits” of the case when the merits are eventually considered by the court. The 5th Circuit ruling blocking the standard argued that because it took OSHA almost two years after the start of the pandemic to issue an ETS, it wasn’t a real emergency and would therefore be declared invalid.

Judge Stranch strongly disagreed, pointing out that an emergency can develop over time, and that conditions have changed significantly since the start of the pandemic. We now have safe and effective vaccines that we didn’t have during the first year of the pandemic, as well as more transmissible and virulent variants such as Delta (and now Omicron.) Therefore, OSHA rightfully considered “the growing and changing virus, the nature of the industries and workplaces involved, and the availability of effective tools to address the virus.”

The record establishes that COVID-19 has continued to spread, mutate, kill, and block the safe return of American workers to their jobs. To protect workers, OSHA can and must be able to respond to dangers as they evolve. As OSHA concluded: with more employees returning to the workplace, the “rapid rise to predominance of the Delta variant” meant “increases in infectiousness and transmission” and “potentially more severe health effects.” OSHA also explained that its traditional nonregulatory options had been proven “inadequate.”

Does the Court Understand the Real World?

To its credit, at least two of the 6th Circuit judges also read the newspaper and are aware that since the OSHA ETS was issued, “The number of deaths in America has now topped 800,000 and healthcare systems across the nation have reached the breaking point.” They also noted OSHA’s observation that the “severity is also likely exacerbated by long-standing healthcare inequities experienced by members of many racial and economic demographics.” And they recognized that “mutations of the virus become increasingly likely with every transmission, contributing to uncertainty and greater potential for serious health effects.”

An Emergency Temporary Standard must address a Grave Danger and it must be necessary to protect workers from that grave danger. The “evidence of the severity of the harm from COVID-19” as well as OSHA’s prediction that the standard would “save over 6,500 worker lives and prevent over 250,000 hospitalizations over the course of the next six months,” justified OSHA’s grave danger finding. In fact, a previous court had stated that just 80 deaths would constitute a grave danger.

The Court also recognized real-world evidence to prove the obvious fact that “COVID-19 is clearly a danger that exists in the workplace,” citing numerous workplace outbreaks before the standard was issued and continuing to this day — many of which were presented to the Court by labor unions.

Union Petitioners illustrate this point as well. Within one week in mid-November, Michigan had reported 162 COVID-19 outbreaks, 157 of which were in workplaces; Tennessee reported 280 COVID-19 outbreaks, 161 of which were in workplaces; Washington state reported 65 outbreaks, of which 58 were in workplaces. And other states similarly experienced outbreaks predominantly in the workplace.

Was OSHA “Staggeringly Overbroad” by Covering Almost All Workers?

An ETS must not just address a grave danger, but must also be “necessary” to protect workers from that danger. Opponents of the standard and the 5th Circuit had argued that OSHA was being “staggeringly overbroad” because OSHA hadn’t proven that vaccines (or testing) were necessary for the protection of all workers in every covered workplace, considering that all workers are not at equal grave danger. The Trump-appointed dissenter in last week’s decision also argued that to prove necessity, OSHA would have to rule out every other alternative measure.

The 6th Circuit disagreed, pointing out that OSHA had tried voluntary guidance as well as enforcement under OSHA’s General Duty Clause, neither of which had protected workers adequately.

“The Fifth Circuit’s conclusion, unadorned by precedent, that OSHA is ‘required to make findings of exposure—or at least the presence of COVID-19—in all covered workplaces’ is simply wrong.”

Then, engaging in a bit of snark unusual in these dry proceedings, Judge Stranch criticized the 5th Circuit for its conclusion, “unadorned by precedent, that OSHA is ‘required to make findings of exposure—or at least the presence of COVID-19—in all covered workplaces’” The court reasoned that “If that were true, no hazard could ever rise to the level of “grave danger” because a risk cannot exist equally in every workplace and so the entire provision would be meaningless.”

Indeed, COVID-19, because it is an airborne disease, is a pervasive hazard for all workers because “American workplaces often require employees to work in close proximity—whether in office cubicles or shoulder-to-shoulder in a meatpacking plant—and employees generally ‘share common areas like hallways, restrooms, lunchrooms[,] and meeting rooms.'”

Was OSHA “Underinclusive” when it exempted small businesses?

While the 5th Circuit had determined that the OSHA standard was “underinclusive,” because it doesn’t cover employers with fewer than 100 employees, the 6th Circuit determined that OSHA had explained its reasons for limiting the scope (a limitation I disagree with because it leaves employees in smaller establishments unprotected and sets a terrible precedent for future OSHA standards.)

Can Congress “Delegate” Authority to Agencies like OSHA?

The 5th Circuit argued that OSHA had also violated the “nondelegation clause,” because Congress cannot “authorize a workplace safety administration in the deep recesses of the federal bureaucracy to make sweeping pronouncement on matters of public health affecting every member of society in the profoundest of ways.” I’ve noted before that OSHA is hardly buried “in the deep recesses of the federal bureaucracy,” and the 6th Circuit judges also noted that “The Supreme Court has long recognized the power of Congress to delegate broad swaths of authority to executive agencies” and that in the OSHAct, Congress had given OSHA the authority to issue workplace safety and health standards as well as Emergency Temporary Standards.

In sum…

In sum, the 6th Circuit rejected the assertions of the Trump-Reagan judges of the 5th Circuit and their bizarre assertion that “From economic uncertainty to workplace strife, the mere specter of the Mandate has contributed to untold economic upheaval in recent months.”

What is actually causing “untold economic upheaval?” Requiring workers to get vaccinated or tested — or new waves of COVID infections and hospitals over-filled with unvaccinated patients?

Whatever “untold economic upheaval” we have experienced already, or will experience in the future, anyone looking outside the windows of a courtroom can see that it is Delta and Omicron that are undermining recent stock market gains, shutting down restaurants, colleges and sporting events, while a large percentage of Americans still refuse to get vaccinated.

So what is actually causing “untold economic upheaval?” Requiring workers to get vaccinated or tested? Or new waves of COVID infections and hospitals over-filled with unvaccinated patients?

The Pizzeria Dissent

The Trump-appointed judge on the panel, Judge Joan Larsen, filed a dissenting opinion, which you can read yourself starting on page 39. I’m not going to get into that, except, for your amusement, the pizzeria example that she used to explain why the ETS was not “necessary.”

One of the main arguments that the plaintiffs, the 5th Circuit and Judge Larsen made was that OSHA had failed to explain “why the rule should apply to a large and diverse class” of workers, instead of just applying to the most vulnerable employees or just to workers in the industries most at risk.

She chose to illustrate the problem using your favorite neighborhood pizzeria. Because who can’t relate to their neighborhood pizzeria?

To illustrate (without intending to trivialize) OSHA’s task, consider the danger from fire in a workplace: a pizzeria. One way to protect the workers would be to require all employees to wear oven mitts all the time—when taking phone orders, making deliveries, or pulling a pizza from the flames. That would be effective—no one would be burned—but no one could think such an approach necessary. What OSHA’s rule says is that vaccines or tests for nearly the whole American workforce will solve the problem; it does not explain why that solution is necessary.

Now I always assume that all judges have a certain, relatively high ability to engage in logical reasoning — even Trump judges. But the pizzeria dissent starting to doubt my assumptions.

To put it simply: The pizza baker may need oven mitts to protect himself from burning his hands, but the worker answering phones in a pizzeria is at no risk — ZERO — of getting burnt pulling a pizza from the flames. So it would be stupid to require the phone answerer to wear oven mitts to answer the phone or the delivery person to wear oven mitts while driving across town.

But every worker in that pizzeria — the pizza baker as well as the person taking phone orders — is at risk of contracting COVID — from each other and from customers. So unlike the oven mitt example, they all need the pandemic-equivalent of oven mitts: a vaccine (or testing and masking.)

And OSHA already addressed those who have (almost) zero chance of contracting COVID on the job — employees who work exclusively out doors or remotely are not covered by the standard.

So what kind of logical legal argument is judge Larsen making? Does it make any sense? Am I missing something? Do I need to enroll in law school?

What’s Next for OSHA’s COVID-19 Standard?

At least three petitions have been field with the Supreme Court asking the justices to block the mandate once again. Generally, they’re using the same old tired arguments: “Ack, everyone’s going to quit! The supply chain will collapse (even more than it already has)! The economy will slump! The sky is falling! And freedom.” Will the Supreme Court listen to reason or are these the proverbial fiery “Gates of Hell” that South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster has vowed to fight to?

Then the 6th Circuit will look at the overall merits and constitutionality of the standard. That process could take weeks or months. The loser of that decision will undoubtedly appeal to the Supreme Court.

There is precedent for the high court allowing vaccine mandates to stand, so we here at Confined Space headquarters are keeping our fingers crossed.

The Elephant in the Room

Meanwhile, even if the Supreme Court listens to reason and decides to let the OSHA standard go forward — at least until the 6th Circuit rules on the merits — OSHA will still need to decide how to handle the clear and growing need for everyone to not just get vaccinated, but to get boosted. Boosters were already recommended to fight off the Delta variant, and now Omicron seems to be cutting through double vaccinated people like tissue paper. In fact, most experts are increasingly considering “boosters” not to be literal boosters, but rather the final stage of a 3-shot regimen needed in order to be “fully vaccinated.”

But the OSHA ETS currently defines “fully vaccinated” as two Moderna or Pfizer shots, or one J&J. In order to redefine what “fully vaccinated” means, OSHA will likely have to wait for CDC (or FDA) or officially redefine “fully vaccinated,” and then go through whatever regulatory contortions are needed to modify the ETS. No ETS has ever been modified mid-stream, so OSHA is in uncharted territory.

Nothing is easy in the regulatory state.

As we all agree, the ETS fails on “b.”

It likely will fail as the 6th hears the case, if the Supreme Court does not first.

That is very good writing. Good work Jordan.