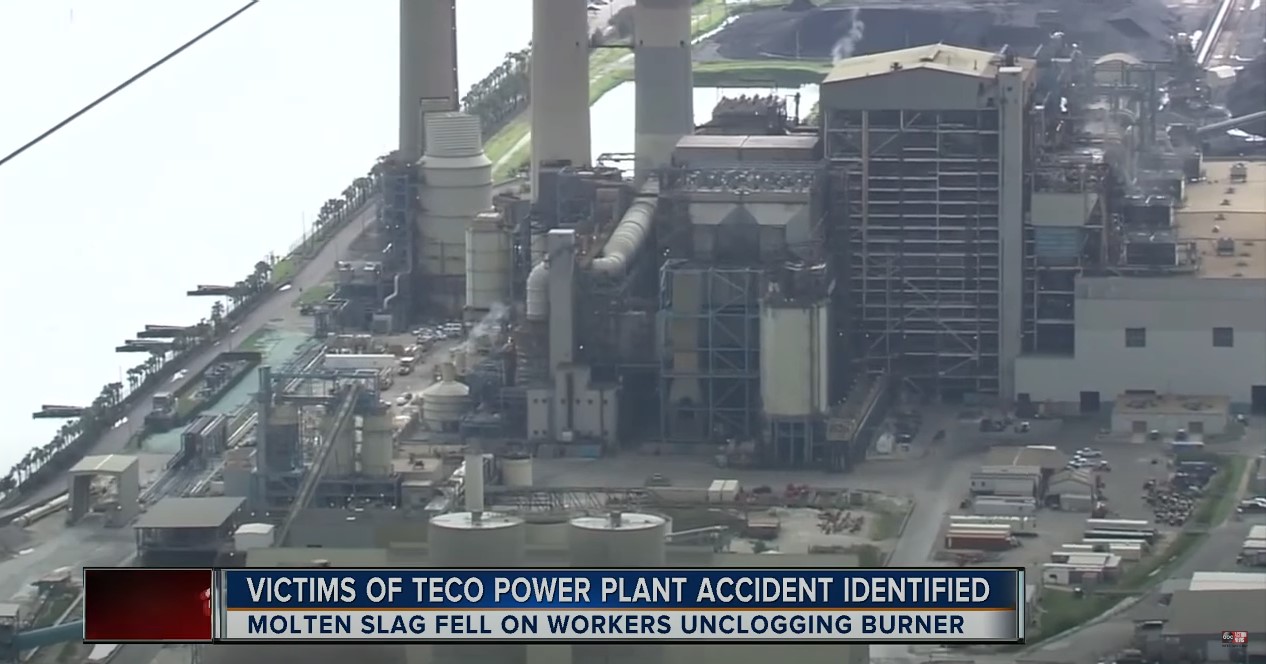

On June 29, 2017, five workers at Tampa Electric — Michael McCort, 60, Christopher Irvin, 40; Frank Lee Jones, 55, Antonio Navarrete, 21, and Amando J. Perez, 56 — were killed at Tampa Electric’s Big Bend Power Station after management forced them to do a procedure that they knew was hazardous. Last week, Tampa Electric (TECO) pleaded guilty in federal court to a criminal charge of willfully violating an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) rule.

The workers were killed when they tried to clear hardened coal slag accumulating at the bottom of a 12-story tall boiler without shutting the boiler down first. Thousands of gallons of molten slag gushed from the boiler, shooting out of the tank and covering the workers. Shutting down and restarting a boiler can cost utilities up to a quarter-million dollars.

I wrote an extensive analysis of the causes of this tragedy here, with a follow-up here and the Tampa Bay Times investigated the tragedy and has been following the aftermath of the explosion.

No Surprise

This was no surprise or “freak accident.” In fact, a similar incident had occurred two decades earlier, in 1997. No one was killed in that incident, but the utility changed its written procedures to prohibit clearing blockages while the boiler was operating. But safety procedures are only useful if workers know about them, and they’re actually implemented. According to the Justice Department, “The work proceeded without observance of several safety-related procedures required by law.” U.S. Attorney Roger B. Handberg for the Middle District of Florida stated that “Had TECO complied with OSHA’s workplace safety standards, conducted a pre-job briefing and followed its own procedure, these senseless deaths could have been prevented.”

Safety procedures are only useful if workers know about them, and they’re actually implemented

The Tampa Bay Times reports that “according to the plea agreement, the slag procedure was not stored in physical form at TECO’s Big Bend Station in Apollo Beach, ‘nor was it easy to locate on the company’s intranet.’ Eight of nine workers interviewed from the day of the 2017 accident said they’d never seen the slag procedure”. In addition, the Tampa Bay Times notes that TECO had a history of safety problems: “From 1997 to 2017, records showed that 10 workers died in accidents at TECO facilities, more than any other energy provider in Florida.”

In December, 2017, OSHA issued citations related to the incident. Tampa Electric (TECO) was fined $139,424 which included two willful violations that were grouped together for one penalty, and two serious Personal Protective Equipment violations that were also grouped together. Gaffin Industrial Services, which employed Irvin and Jones, received two serious citations and a $21,548 penalty for five violations for failure to provide personal protective equipment that would have protected workers against burns.

Plea Agreement

As part of the plea agreement,

TECO admitted to willfully failing to hold a pre-job briefing with the workers performing the work. Such briefing should have included the procedures for the water blasting work. Instead, the work proceeded even though the procedures could not be found. As a result, certain critical safety-related steps were not taken, including lowering the amount of coal entering the furnace, and shutting the unit down after a specified interval had lapsed.”

According to the Tampa Bay Times:

The plea agreement, filed Friday in U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida in Tampa, requires TECO to pay up to a $500,000 fine. The government will ask for a sentence of three years’ probation, including payments to the victims’ families and requiring TECO to implement a safety compliance plan. In a statement, TECO president and CEO Archie Collins said the company took “full responsibility” for the accident.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHAct) limits criminal prosecutions to those cases where a willful violation caused the death of a worker. Even then, it’s only a Class B Misdemeanor which often discourages the Department of Justice from pursuing criminal indictments under the OSHAct. Since passage of the OSHAct in 1970, according to the AFL-CIO, only 115 cases have been referred for prosecution under the act even though approximately 425,000 workplace were killed on the job over that period. This case was prosecuted by DOJ’s Environmental Crimes Section.