The following post is somewhat long and complicated. Read it anyway.

At its core, this is the same age-old story of corporate greed: How rapacious mine operators who have subjected generations of miners to disabling and fatal black lung disease, then managed to transfer their responsibility to pay benefits to suffering coal miners from their own coffers to the taxpayer’s pockets.

Yet it is the complexity of this story helps hide this scandal from the American public, even though the result is that the taxpayers are bailing out wealthy coal operators for costs of black lung disease that has doomed tens of thousands of mineworkers over the past half century.

So, sit back, pour yourself a drink, and spend a few minutes to understand how coal operators and Wall Street continue to manipulate the law and threaten miners’ health while picking taxpayers’ pockets.

Black lung disease has contributed to the deaths of more than 76,000 coal miners since 1968. Facing rank-and-file uprisings across the Appalachian coal fields, Congress passed the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 (Coal Act) to improve safety and health standards for miners and institute the first enforceable coal mine dust standard. That standard drove down black lung rates for 20+ years.

Until it didn’t.

Black lung disease has contributed to the deaths of more than 76,000 coal miners since 1968.In the early 1990s, the most severe form of black lung disease (known as progressive massive fibrosis), came back with a vengeance driven by higher silica exposure.

In the early 1990s, the most severe form of black lung disease (known as progressive massive fibrosis), came back with a vengeance driven by higher exposure to silica in coal mines. In 2018, NIOSH reported one in five long tenured miners in Central Appalachia was diagnosed with black lung disease—a rate not seen in 25 years.

The 1969 Coal Act also included a national compensation system for miners suffering from black lung disease. That program, which is now administered by the Department of Labor (DOL), provides totally disabled miners and survivors with $738 per month plus related medical costs, and another $368 per dependent up to a maximum $1,475 for a family of 4. Obviously, no one is getting rich by winning a claim for preventable lung disease that suffocates its victims.

Who is Responsible for Paying Black Lung Benefits?

In general, mine operators are responsible for paying black lung benefits. But coal operators use bare-knuckle tactics to fight miners’ black lung claims, making it an uphill battle for claimants to secure the benefits they have earned.[1]

As part of the claims process, DOL identifies the miner’s last coal mine employer (where the miner was employed 12 months or more) who is deemed the “Responsible Operator” liable to pay any black lung benefits awarded. To ensure that mine operators have the funding to pay the miners’ benefits, operators must purchase workers’ compensation insurance to cover black lung benefits.

Or there is another option: mine operators are allowed to self-insure — if they can demonstrate to DOL that they have secured the necessary assets to cover their black lung liabilities.

That’s an attractive option for many coal operators since self-insuring often costs less than buying workers’ compensation insurance. But how does DOL make sure that the self-insured operators have the full amount reserved for current and future benefits? And how can these assets be secured before there is a bankruptcy?

Under current rules, to self-insure, operators must have been in the business of coal mining for at least three years, and must demonstrate to DOL that they have necessary assets to cover their black lung liabilities by obtaining collateral in the form of an indemnity bond, placement of assets in escrow, or a letter of credit in the amount necessary to secure payment of benefits.

That way if (or when) they go bankrupt, the funds are there to pay benefits —in theory. But who pays if the coal operator goes bankrupt and didn’t have enough commercial insurance or secured assets (such as an indemnity bond) to pay black lung benefits?

In cases where no responsible mine operator could be identified, or the operator went of business, or filed for bankruptcy, the benefits are paid by the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund (Trust Fund), which was established in 1978 by the Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1977.

The Trust Fund, which is based in the U.S. Treasury Department, is financed by an excise tax on coal tonnage amounting to $1.10/ton for underground coal and $0.55/ton for surface mined coal. The tax is paid by mine operators for coal sold domestically. But the revenues from that tax have never been sufficient to cover the Trust Fund’s expenses. The Trust Fund is currently approximately $6 billion in debt.

A Shrinking Industry

It is fair to say—with limited exceptions—that coal mining is a rapidly shrinking industry in the US. Bankruptcies have proliferated because there is only half as much domestic coal mined as there was a decade ago. The excise taxes needed to fund the Trust fund are falling in lock step (and exported coal is exempt from that tax).

But miners who contract disabling black lung—and their survivors–will still need to receive benefits until death, even though the coal industry is shrinking. This liability “tail” could last as long as 50 years, according to a DOL memo from the Trump Administration.

The bad news is that if the Trust Fund is insolvent, it’s the taxpayers – you and me – who end up paying benefits for miners with black lung instead of the coal companies that caused the problem in the first place.

The good news is that even if the Trust Fund does not have sufficient resources to pay benefits, miners’ black lung benefits are still OK because the Trust Fund is authorized to borrow from the U.S. Treasury if its short of funds.

The bad news is that ultimately, if the Trust Fund is insolvent, it’s the taxpayers – you and me – who end up paying benefits for miners with black lung instead of the coal companies that caused the problem in the first place.

Dodging Liability

Congress stated clearly that coal operators, instead of taxpayers, would shoulder the cost of black lung when it set up the Trust Fund. The Trust Fund was intended to be a backstop for miners rather than a means for coal operators to underinsure their liabilities.

But over the past decades, many self-insured coal operators have perfected the art of dodging liability when it comes to coughing up (pardon the expression) the money to pay for black lung benefits,

This turned the purpose of the Trust Fund on its head.

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), instead of the Trust Fund serving as an emergency backup, it became the main means by which a number of self-insured coal operators have cleverly offloaded around $1 billion in their liabilities while providing as little as three percent in collateral.

Over the past decades, many self-insured coal operators have perfected the art of dodging liability when it comes to coughing up the money to pay for black lung benefits,

In January 2023, DOL estimated that self-insured operators have another $700 million in self-insured black lung liabilities, but reserved only $120 million (17%) in collateral. For example, DOL authorized Alpha Natural Resources (ANR), one of the largest coal operators in the country, to post only $12 million in collateral for its self-insured liabilities. Yet, when Alpha filed for bankruptcy in 2015, nearly $500 million in black lung liabilities were transferred to the Trust Fund, according to the GAO. That means that Alpha was off the hook for a mere 3% of its liabilities.

The GAO found big problems with DOL’s current rules because they do not require sufficient collateral to cover both current and future black lung liabilities. DOL is not currently required to update coal operators’ collateral levels on a regular basis to ensure that the coal operators have enough money set aside to fund their black lung liabilities.

Gaming the Department of Labor

But failing to reserve enough money to cover black lung benefits is only one way for coal operators and Wall Street to game the system. Another way is to transfer these liabilities to a spin off company, which, when it files for bankruptcy, makes the liabilities disappear.

Peabody Coal, for example, spun-off a new coal company out of its eastern U.S. mines in 2007 and saddled the new company with an insurmountable burden of black lung, pension, and health care liabilities, but with far too few assets to pay the bills. This new, stand-alone enterprise was named Patriot Coal.

Through this two-step process—a spin-off followed by an inevitable bankruptcy- (Patriot declared bankruptcy in 2015),-Peabody jettisoned decades of black lung liabilities from their balance sheet. Although Patriot and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) contended Peabody’s spin-off was a fraudulent conveyance, in the end DOL was left holding the bag to the tune of nearly a quarter billion dollars in black lung liabilities.

With the spinoff, Peabody rid itself of about $600 million of retiree-healthcare liabilities, along with hundreds of millions of dollars of other liabilities, including environmental-reclamation obligations and black-lung benefits.

The UMWA explained in their April 19, 2023, comment letter to DOL:

Patriot inherited only 13% of the parent company’s coal reserves, but according to one executive, the spin off meant that “our retiree, health care liability and related expense will be reduced by about 40%” and added “that workers’ compensation liability will be cut by nearly 90%”. As many as 13 self-insured subsidiaries were spun out of Peabody into Patriot. Patriot also acquired 3 operators from Arch Coal that had self-insured liabilities.

The Patriot boondoggle wasn’t a big surprise: more like that bad dream where the train is bearing down on you, but your feet are stuck in molasses.

Even when DOL does periodically update operators’ required collateral levels, the operators are able to kick-the-can-down-the-road by filing appeals that languish for years in DOL. For example, DOL had seen Patriot’s bankruptcy on the horizon in 2014 – a year before Patriot declared bankruptcy — and requested that Patriot increase its self-insurance collateral from $15 million to $80 million.

Patriot appealed. But DOL had no quick procedure to deal with appeals, so in the eight months while the appeal was languishing, Patriot filed for bankruptcy, and eventually transferred $230 million in black lung benefit liabilities to the Trust Fund. The $15 million in collateral amounted to only 6% of the collateral needed to fund their black lung liability, according to the GAO.

Gaming the Bankruptcy System: 3 Easy Steps to Escape Liability

Professional Wall Street creditors aren’t dumb. They’re rich. And there’s a reason.

In this case, they have developed a clever workaround that allows them to handcuff DOL’s ability to recover the cost of black lung benefits from self-insured operators in bankruptcy. Of course, keeping DOL at bay means that creditors pocket more money from a bankruptcy.

It’s a complicated – but ingenious –3-step process. So follow closely:

Under current law, DOL, as a Trustee for the Trust Fund, may only place a lien (or legal claim) on assets if the self-insured operator defaults on (or stops) paying benefits to miners.

And if there is a default, DOL gets the money first before other creditors in bankruptcy.

That’s bad for the vultures of Wall Street, so their clever lawyers figured out how to empty out the money bag before DOL – and taxpayers — get to place a lien.

Step one: After declaring bankruptcy, creditors and the operator get the judge’s approval to keep paying miners’ monthly benefits during the bankruptcy court proceedings. So, no default…yet.

Step two: The operator waits to default on monthly benefit payments to miners until after the bankruptcy court distributes all assets to the secured creditors.

“The winners are the coal operators and their Wall Street creditors. The losers are the American taxpayers.” — Rep. Alma Adams (D-NC)

Step three: A couple of weeks after all the assets have been distributed–after the money bag has been emptied out–the operator notifies DOL that (oops!) they are unable to pay benefits to miners. With this default, DOL is now finally entitled to place a lien on the company’s remaining assets.

The problem is that (presto!) there are no assets left. All the Trust Fund gets is whatever insufficient collateral had been set aside prior to bankruptcy…and a mountain of liabilities.

Alma Adams (NC-12), former-Chair of the House Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, noted at a February 26, 2020, hearing on the Trust Fund: “What we are seeing here is nothing less than a gaming of the system. The winners are the coal operators and their Wall Street creditors. The losers are the American taxpayers.”

DOL Proposes a Fix

To head off these schemes to evade the costs of black lung, DOL issued proposed rule last January that would tighten up its self-insurance rules by implementing most of the GAO’s recommendations.

The proposed rule which would require self-insured operators to provide surety equal to 120% of their current and future black lung benefit liabilities. This reform would plug the leaky bucket and prevent the egregious abuse of the system.

However, this reform is causing no shortage of gnashing of teeth, if not hysteria, in the C-suites of the coal companies. The same coal companies that gamed the system are now claiming that the new DOL proposal will drive them to the brink.

The National Mining Association (NMA), for example, contends that the added red ink (and the risk of more) is too insignificant to justify reforms to self-insurance. Nothing to see here folks.

New rules proposed by the Department of labor are causing no shortage of gnashing of teeth, if not hysteria, in the C-suites of the coal companies. The same coal companies that gamed the system are now claiming that the new DOL proposal will drive them to the brink.

Alpha Metallurgical Resources (the successor to ANR) in a joint letter with Warrior Met Coal blasted the DOL’s proposal as “unsound legally and bad public policy” and would “substantially decrease liquidity and interfere with current operations and financial position.”

They argue that it’s not fair for DOL to change the rules because they had already made “irreversible business decisions based on DOL’s historic practices.”

In other words, we’ve become dependent on your failed rules, so it’s not fair to fix them now.

Unpacking these arguments, it appears these operators simply want to continue to under-insure, because it is cheaper, and they know the risk from under-insurance will just be transferred to the taxpayers, via the Trust Fund.

Given that the predecessor to Alpha Metallurgical Resources was able to shift nearly $500 million in liabilities to the Trust Fund while providing less than 3 percent collateral, what rational executive wouldn’t want to keep this sweet deal?

Warrior Met is crying foul that DOL is proposing to boost their surety bonding from $21 million to $68 million. But this company has been awash in cash in recent years, having transferred around $1.5 billion in dividends to their shareholders and $50+ million in stock buybacks since 2017.

So cry me a river.

In an April 19, 2023, comment letter, Peabody Coal criticized DOL’s proposal requiring them to post collateral equal to 120% of their estimated liabilities, because this means they would have to set aside money that could go to its shareholders. And they are refreshingly honest about it.

Peabody says it has “$1.3 billion in cash on the books”, and just announced a $1 billion stock buy-back plan. They argue that this rule would tie “up cash and/or Letter of Credit capacity that prevents the company from operating efficiently.” Their loyalty is to their shareholders, not their ailing workers. So for Peabody executives, the current status quo is just fine.

Peabody also contends that they should be not have to post 120% collateral, because they “paid $32.4 million in black lung excise tax to fund the trust fund” last year. They write:

“If the collateral [collected from operators] completely eliminates any possibility of the trust paying claims, then it calls into question the purpose for the fund and the excise tax.”

Apparently, Peabody overlooked that the Trust Fund is $6 billion in debt, which includes close to $230 million in Peabody’s black lung liabilities that were transferred to the Trust Fund via the Patriot Coal bankruptcy. Perhaps the Peabody executives wanted to skip over that inconvenient fact. Or maybe just forgetful. However, paying the modest excise tax is a good way to start repaying the debt and restoring solvency to the Trust Fund.

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the Appalachian Citizens Law Center, the National Black Lung Association, Appalachian Voices, and a related citizens petition signed by 4800+ individuals addressed many of the industry’s objections (and suggested improvements):

- The 120% collateral requirement is reasonable: Many state workers’ compensation programs require more than 100% in collateral from self-insured employers. For example, Alaska requires 125%, Arizona requires 125%, Minnesota requires 110%, North Carolina requires 100%, Tennessee requires 125%, and Texas requires 125% (although workers’ comp is optional in Texas).

- Requiring 120% collateral provides a buffer for rising medical costs and more claims: As documented by NIOSH, the most severe form of black lung is increasingly diagnosed in younger miners; meanwhile, procedures such as lung transplants—which will cost north of $1 million—are available for some miners.

- Operators have multiple options to cover the costs of black lung: They don’t have to self-insure if it is too costly under this rule; they can simply purchase commercial workers’ compensation insurance. Nothing in the Black Lung Benefits Act requires DOL to adopt a rule that permits operators to self-insure for less than current and future liabilities. If an insurer won’t cover past liabilities, operators can post collateral such as Treasury bills from which they can draw interest. What operators cannot do is get a free ride.

Why Do We Care?

The solvency of the Trust Fund is integral to the workings of the Black Lung program, and miners and taxpayers face multiple risks by allowing operators to pile more red ink on the taxpayers.

Political risk: Future Benefit Cuts?

When the Trust Fund faced a growing mountain of debt in 1981, the industry won legislation to cut benefit eligibility in exchange for a higher excise tax rate. It took until 2010 when the Affordable Care Act was passed, to reverse these deep benefit cuts; but in that 30-year window far too many miners and survivors were denied benefits.

Last year, House Education & Labor Republicans offered an amendment during a mark-up that could coerce miners into accepting a partial settlement in lieu of full benefits. The Black Lung Association (BLA), which advocates for miners safety and benefits, warns that growing debt levels in the Trust Fund could once again be used by the industry as political cover to cut miners’ benefits.

Evading black lung payment provides far less incentive for coal operators to control dust to a low enough level that prevents black lung disease over a lifetime of work.

Perverse Incentives: More Black Lung?

The BLA points out that allowing self-insured operators to dodge payment for black lung benefits establishes a perverse incentive, whereby a significant cost—compensating black lung disease from the failure to control harmful dust levels–is not included in the cost of coal production. While internalizing these costs will not ensure safer mines—that requires much stronger standards and enforcement—evading payment provides far less incentive for coal operators to control dust to a low enough level that prevents black lung disease over a lifetime of work.

Moral Hazard: Taxpayers Pay for Operators’ Cost Shifting?

Government permission to under-insure current and future benefits means the Trust Fund (and taxpayers if it is insolvent) will subsidize the cost of black lung disease. This creates a moral hazard where responsible coal operators have little incentive to guard against that risk because they are improperly allowed to shift the cost to taxpayers.

As Senator Robert C. Byrd noted in 2010, “…black lung benefits have been promised to coal miners who have acquired this totally disabling disease through no fault of their own…[it would] not cost [companies] one additional dime, unless [these] employers took insufficient precautions to protect their workers from black lung disease.

Footnote

[1] For more information on how the coal operators fight miners black lung claims, read Soul Full of Coal Dust The True Story of an Epic Battle for Justice, a gripping story by award-winning investigative journalist Chris Hamby about how the coal industry, backed by their stable of the best attorneys and “expert” doctor money can buy, cheated thousands of miners suffering from black lung, out of the compensation they deserved. You don’t know whether to cry at the tragedy or feel gratified by the dedication of those who spent their careers fighting for the miners.

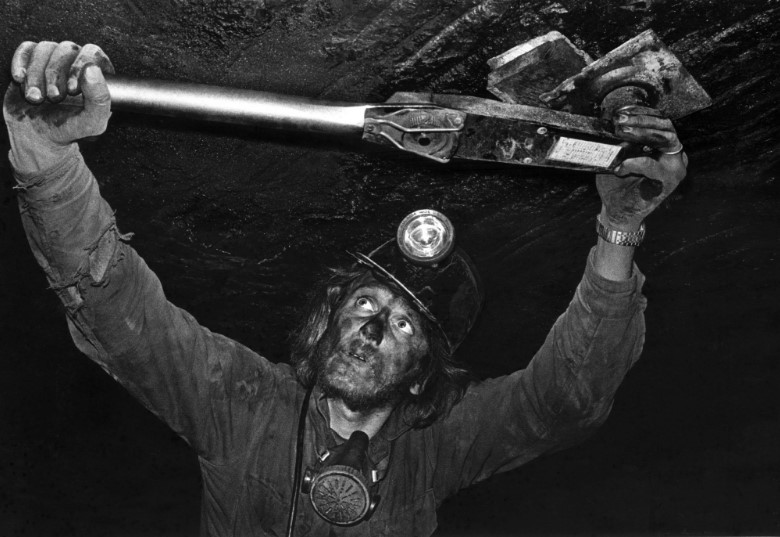

Top photo by Earl Dotter.