Thirty-nine years ago, the city of Bhopal, India suffered the worst chemical disaster in world history. I wrote a long post about Bhopal in 2004, the 30th anniversary of the disaster which you can read here. The leak of methyl isocyanate that began at a Union Carbide pesticide plant a few minutes after midnight of December 2, 1984, killed up to 25,000 people, that night and in the months and years following the disaster.

The tragic stories remain sickening, ever decades later.

As the toxic cloud blanketed much of Bhopal, people began to die. Aziza Sultan, a survivor, remembers: “At about 12.30am, I woke to the sound of my baby coughing badly. In the half-light, I saw that the room was filled with a white cloud.

“I heard a lot of people shouting. They were shouting ‘Run! Run!’,’ she says. ‘Then I started coughing, with each breath seeming as if I was breathing in fire. My eyes were burning.”

Champa Devi Shukla recalls: “It felt like somebody had filled our bodies up with red chillies; our eyes had tears coming out, noses were watering, we had froth in our mouths. The coughing was so bad that people were writhing in pain.

“Some people just got up and ran in whatever they were wearing, or even if they were wearing nothing at all. People were only concerned as to how they would save their lives, so they just ran.”

In those apocalyptic moments, no one knew what was happening. People started dying in the most hideous ways. Some vomited uncontrollably, went into convulsions and dropped dead. Others choked, drowning in their own body fluids.

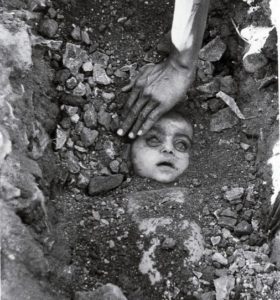

Many people died in the stampedes through narrow alleyways where street lamps, swamped in gas, burned brown. The crush of fleeing crowds wrenched children’s hands from their parents’ grasp. Families were literally ripped apart.

And the pain lingers. Over 150,000 people continue to suffer from respiratory diseases, kidney and liver disorders, cancers and gynecological issues caused by the accident and exposures long after the incident.

Many people died in the stampedes through narrow alleyways where street lamps, swamped in gas, burned brown. The crush of fleeing crowds wrenched children’s hands from their parents’ grasp. Families were literally ripped apart.

Multi-Generational Damage

Now a new study has come out, showing

the accident – often considered the worst industrial disaster in history – affected not just those who were exposed to the gas that night but also the generation of babies still in the womb when the accident happened. In fact, men born in Bhopal in 1985 have a higher risk of cancer, lower education accomplishment and higher rates of disabilities compared with those born before or after 1985.

“The paper is one of the first papers to demonstrate clearly this link between a huge industrial disaster and the effect on children in utero,” says Jishnu Das, a public policy professor at Georgetown University and a fellow at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi.

“Not only are we finding high rates of cancers, but also all kinds of immunological issues, neuro skeletal issues, musculoskeletal issues and huge number of birth defects in children being born to gas-exposed parents,” says Rachna Dhingra, who works with the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal, an advocacy organization.

Prashant Bharadwaj, an economist at University of California San Diego and an author of the new study used data collected in 2015-2016 by the National Family Health Survey, which asks every family India about health, education and economic outcomes.

“It’s interviewing women, getting all of their life history, including when they had children, whether those children survived, when those women themselves were born, their educational attainment, their level of health,” says study co-author Gordon McCord, also an economist at UCSD. The survey interviewed men, too.

“So we were able to piece all these together to say, okay, let’s look at the children who were born in the years right before 1984, in ’85, and then afterward,” says McCord.

Then they compared the people born in 1985 to those born before and after the accident to see if there was anything distinct about the 1985 cohort, which was exposed to the accident in utero. They found an increase in pregnancy loss, which they expected, based on previous research. But the analysis also illuminated something new about those pregnancy losses – the losses were likely to involve male fetuses.

“That 1985 birth cohort was very strange because it had a much lower male-to-female sex ratio” compared to the other birth cohorts in the study, says McCord.

A range of previous studies have shown that, in general, male fetuses are more vulnerable to any adverse effects in utero, says McCord. “And so when you get an adverse health shock to pregnant women, the likelihood of losing the male fetus is a bit higher.” And the males born in 1985 in Bhopal were unlike those who were born before or after, he adds. In fact, they are worse off in terms of health and employment even when compared to those who lived through the disaster. “They have a higher likelihood of reporting to have cancer,” he says. “They have a higher likelihood of reporting a disability that prevents them from being employed. And they on average have two years less of education.”

The study also raised the issue of what is owned to future generations from the government or companies involved in the catastrophe. Rachna Dhingra, who works with the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal, an advocacy organization, points out that

“Not a single child who was in utero or born after the disaster was ever compensated,” says Dhingra.

The Supreme Court in India in March also rejected a plea for more compensation of survivors of the Bhopal accident. “The damages to the people who were directly exposed — all the curtains have been closed,” says Dhingra.

But the curtain is still open for figuring out “damages to the next generation,” she adds. And that’s where she hopes the new study’s findings will make a difference.

Union Carbide paid a measly $470 to compensate victims of the disaster, and Dow Chemical which later bought Union Carbide, continues to absolve itself of any responsibility, claiming that the chemical industry’s “Responsible Care” safety program has solved all of our problems. “Dow… has steadfastly refused to clean up the Bhopal site. Nor has it provided safe drinking water, compensated the victims or shared with the Indian medical community any information it holds on the toxic effects of MIC.”

Dow’s website continues to refer to Union Carbide’s old website which blames the Bhopal disaster on debunked theory that the disaster was caused by sabotage committed by the plant’s workers. Meanwhile, Dow has had the second highest number of chemical plant incidents in the US since 2003. Dow was also the second biggest federal lobbying spender of the chemical industry in 2022.

Dow’s website continues to refer to Union Carbide’s old website which blames the Bhopal disaster on debunked theory that the disaster was caused by sabotage committed by the plant’s workers.

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch

The other question that we have to ask ourselves every year at this time is how vulnerable we still are in this country, as well as around the world. Safety of the thousands of chemical facilities in this country has improved significantly since Bhopal. OSHA’s Process Safety Management standard and EPA’s Risk Management Program, both mandated by Congress shortly after Bhopal, improved chemicals safety in this country. But both are over 30 years old and in dire need of modernization. EPA is on the verge of issuing a new regulation updating some parts of the 1992 regulation, but OSHA remains many years away from its PSM update.

And troubling incidents remain far too common in this country. The 2005 BP Texas City refinery explosion which killed 15 workers, as well as the 2013 West chemical explosion that also killed 15 emergency responders and town residents are the most well-known recent chemical disasters, but smaller incidents which gain little lasting attention are still all too frequent. And, of course, chemical disasters are not confined to fixed facilities, as the recent East Palestine train derailment showed. More recently, last October, a tanker truck carrying caustic anhydrous ammonia, overturned in Teutopolis, Illinois, a town northeast of St. Louis, spilling more than half its 7,500-gallon load, killing 5 people. One driver and his two children died in the release.

The safety of these “chemical plants on wheels” are the responsibility of the Department of Transportation, rather than OSHA or EPA.

Bhopal Coming to a Television Near You

I noted a few years ago that few Americans know about the Bhopal disaster. Most young people have never heard of Bhopal. Now, however, a new 4-part Netflix series, “The Railway Workers,” tells the story of railway workers who saved many lives during the disaster. I haven’t watched it yet, but it’s moved to the top of my watch list. Rachna Dhingra, who works with survivors Bhopal notes that “The makers have highlighted corporate machinations and governmental apathy behind the disaster and its long aftermath with clarity.” Dhingra notes that survivors are sill marching for justice.

Hopefully the series will awaken some curiosity about chemical plant safety in this country, and renewed pressure for improved chemical plant safeguards.

Of course, ultimately, it is the workers themselves — through their unions (where they exist) — that are the best guarantees of safe workplaces.

Of course, ultimately, it is the workers themselves — through their unions (where they exist) — that are the best guarantees of safe workplaces.

Because as I mentioned above, whether you live near a chemical plant, a rail line or a highway, you can run, but you can’t hide. As I wrote almost 20 years ago,

And finally, look homeward. The issue of chemical plant safety is again being raised as homeland security concerns focus attention not only on the vulnerability of plants to terrorist attacks, but at the inherent dangers of the chemical industry, especially for plants located near highly populated areas. I point you to a little noticed incident last June when Gene Hale and her daughter, Lois Koerber died from exposure to chlorine fumes over a mile away from where two trains collided, releasing a deadly cloud of chlorine gas. Sometimes late at night I think about this accident as I listen to the freight trains passing less than half a mile from my home. Tonight, at five minutes after midnight, I’m thinking about Bhopal, as well.

More Reading

The long, dark shadow of Bhopal: still waiting for justice, four decades on, The Guardian

The world’s worst industrial disaster harmed people even before they were born

Henry Kissinger’s Controversial Link To Bhopal Gas Tragedy Case, NDTV

Bhopal Gas Tragedy: The Railway Employee Who Saved Thousands of Lives

20th Anniversary of Bhopal, Confined Space (2004)

Cover photo credit: Judah Passow, The Guardian

The Bhopal tragedy was an important precursor of OSHA’s Severe Violator program. After Bhopal, OSHA was tasked with inspecting methyl isocyanate plants in the US to determine whether they posed a health risk to surrounding communities. In the course of the inspection of the Union Carbide facility in Institute, WV, it was discovered that UC maintained two sets of OSHA injury logs — one for internal use and sharing with its WC insurer, and another to show OSHA during the then-prevalent ‘Records Only’ inspection initiative (a policy disaster if ever there was one). When Secretary of Labor Bill Brock learned about the subterfuge, he ordered OSHA Assistant Secretary Gerry Scannell to develop a truly deterrent penalty policy. The result, conceived by senior officials of OSHA and the Office of the Solicitor of Labor, was the instance-by-instance (Egregious) penalty policy, to be deployed, as once described by Solicitor Bob Davis, when the OSHA violations were ‘bad enough to make us mad enough.’ A series of recordkeeping inspections of large corporations folliwed, leading to an enforcement focus on the meatpacking industry, ergonomic hazards, chemical plants, lead smelters, and many more. It’s a shame that it took a horrible tragedy for the administration to realize that without truly deterrent penalties, OSHA was toothless. But Bhopal helped elevate OSH compliance among Fortune 500 companies.

Thanks, Jordan. I remember the whole thing vividly. The chemical industry has managed to kill every single effort to improve the law despite the realization in the wake of 9/11 that sabotage of supposedly modern plants in the exceptional U.S. could cause thousands of casualties. You do a great service by reminding us of all this.

I love reading your entries. I am a retired Federal OSHA employee. Peace