The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its annual Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) reported today that 5,486 workers died in the United States in 2022 from fatal injuries suffered on the job. This was a 5.7-percent increase from 5,190 workplace fatalities in 2021. The rate of workplace deaths rose as well in 2022, up from 3.6 to 3.7 per 100,000 workers in 2021.

5,486 workplace deaths translates into one death every 96 minutes: 15 every day, over 100 every week.

Fatality numbers went way down in 2020, mainly because fewer workers were working during a year of COVID-19 related shutdowns. Those numbers began rising again in 2021 and now exceed the pre-COVID workplace fatality numbers. Note that these deaths are traumatic fatal injuries and do not include deaths resulting from occupational illnesses like COVID-19, silicosis, liver disease or cancer. It is estimated that 120,000 workers die from occupational disease each year.

5,486 workplace deaths translates into one death every 96 minutes: 15 every day, over 100 every week.

These are just numbers. Most worker deaths remain hidden from the average person. In the Weekly Toll, I attempt to capture the the daily workplace tragedies, something about why it happened and attach a name to workers killed on the job. But as avid readers know, I rarely find more than around one-fifth of all the workers killed every week on the job.

The “Highlights”

Not much good news here. Some of the “highlights” include

- Workplace violence fatalities climbed almost 12 percent to 849 in 2022, compared to 761 in 2021. Homicides accounted for 61.7 percent of these fatalities, with 524 deaths, an 8.9-percent increase from 2021. Almost a quarter of fatalities due to homicides occurred while a worker was tending a retail establishment or waiting on customers. Homicides resulting from shooting were up over 12 percent.

Fatalities among protective service occupations (such as security guards) increased 10.9 percent in 2022, rising to 335 from 302 in 2021. The rate for this occupational group increased to 10.2 fatalities per 100,000 FTE workers in 2022, up from 9.4 in 2021. Homicides (121) and suicides (17) accounted for 41.2 percent of these fatalities.

- Heat and other temperature extreme-related deaths rose 18.6% in 2022, climbing to 51 from 43 in 2021. Heat related deaths rose to almost 20% to 43 in 2022, from 36 in 2021. (Heat-related deaths are generally recognized to be undercounted as they often emulate heart attacks and other “natural causes.”)

- Drug overdoses increased 13.1 percent to 525 fatalities in 2022, up from 464 in 2021. This continues a trend of annual increases since 2012 and is the highest ever recorded.

- 1620 workers in transportation and material moving occupations were killed in 2022, again representing the occupational group with the most fatalities.

- The next most deadly occupations were construction and extraction workers with 1,056 fatalities, an 11.0-percent increase from 2021. Extraction workers include workers who run machinery and equipment designed to extract gas, oil or mine minerals from the earth. 423 of these deaths were a result of falls, slips, or trips. And the fatality rate for this group climbed from 12.3 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2021 to 13.0 in 2022. Roofers had the highest death rate for construction workers.

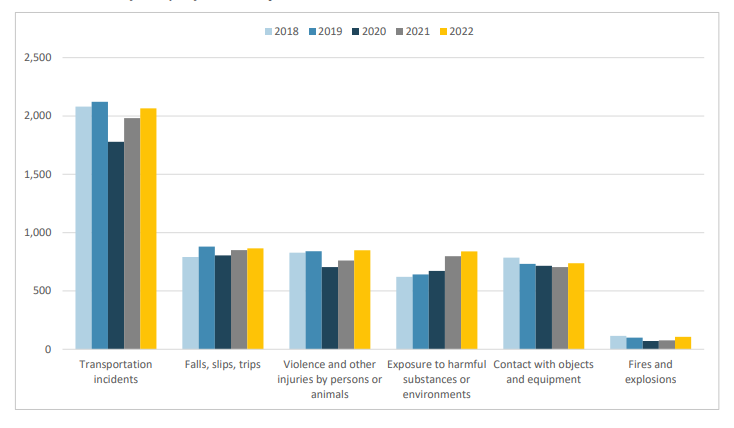

- Transportation incidents again remain the most frequent type of fatal event accounting for 37.7 percent of all occupational fatalities. Deaths of driver/sales workers and truck drivers increased by 8percent from 2021 to 2022.

- Farming, fishing, and forestry occupations had the highest fatality rate, up from 20 fatalities per 100,000 workers in 2021 to 23.5 in 2022. Loggers had the highest rate in this category at an astonishing 100.7 (compared with

Workers of Color, Women and the old Folks

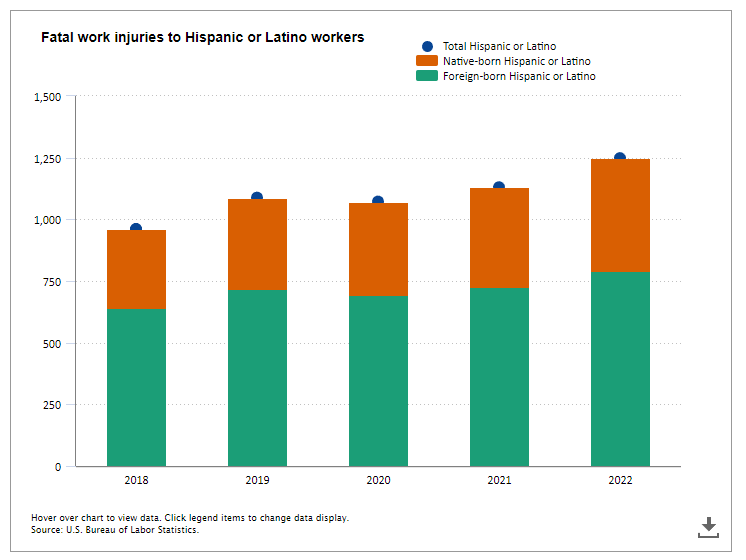

African American and Latino workers experienced higher rates of workplace deaths, increasing from from 4.0 to 4.2 for black workers, and 4.5 to 4.6 for Hispanic workers. 1248 Latino workers were killed on the job in 2022, compared with 1130 in 2021. Fatalities for Black workers rose from to 653 to 734.

The most likely cause of death for both groups was transportation incidents. That was followed by workplace violence for Black workers, and falls, slips, or trips for Latino workers.

Fatalities in the construction industry accounted for almost 40 percent of foreign-born Hispanic or Latino worker deaths in 2022.

African American workers were particularly hard hit by homicide deaths. Whereas Black worker fatalities accounted for 13.4 percent of all fatalities in 2022, they represented 33.4 percent of fatalities from homicides.

1248 Latino workers were killed on the job in 2022, compared with 1130 in 2021. Fatalities for Black workers rose from to 653 to 734

Women were also disproportionately hard hit by homicides. Whereas women made up only 8.1 percent of all workplace fatalities in 2022, they accounted for over 15 percent of total homicides. Homicides were 18% of total fatalities suffered by women, versus only 9% of fatalities for men.

Older workers, in the 55 to 64 age group, continued to have the highest number of fatalities of any age group in 2022, up over 3 percent from 2021. Transportation incidents were the highest cause of fatalities for this age group, followed by falls, slips, and trips. This is especially concerning considering that a Pew Research Center study issued last week found that roughly one-in-five Americans ages 65 and older were employed in 2023 – nearly double the share of those who were working 35 years ago.

Conclusion: What Is To Be Done?

Too many workers continue to die in this country, mostly from preventable causes. OSHA’s budget and legal constraints don’t help matters, nor do its low penalties. Many of the leading causes of death — such as most transportation incidents don’t come under OSHA’s jurisdiction, and other leading causes of death, such as workplace violence, have no OSHA standards, leaving the agency at a disadvantage when attempting to enforce safe working conditions.

Unfortunately, OSHA has been making little progress on its workplace violence standard — which will only cover healthcare and social service workers. No date has been set for issuance of an official proposal, so we are unlikely to see a proposal in this Presidential term and it will be several years before we see a final standard — assuming there is a second Biden term. A heat and comprehensive infectious disease standard are also many years in the future.

If we are ever going to significantly reduce the number of workers killed on the job every year, we’ll need far more workers to join unions that can use bargaining, the grievance procedure and even strikes to enforce safe working conditions. We need a more powerful, better funded OSHA that can issue more standards more quickly, with enough inspectors to reach more workplaces more frequently and civil and criminal penalties strong enough to effectively deter employers from cutting corners on worker safety. And we need changes in the Occupational Safety and Health Act to will enable OSHA to more easily enforce safe working conditions. Congress needs to pour more money into OSHA, not less.

AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler stated:

At a time when we should be bolstering workplace safety and holding corporations accountable, the labor appropriations bill put forward by House Republicans proposes cuts to funding for both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA). These agencies are essential to keeping workers safe on the job, and any effort to defund them is a frontal assault on the safety and lives of working people.

Maintaining a safe workplace should not be partisan; a bipartisan Congress established this right under the law more than 50 years ago. Significant hazards like workplace violence and occupational heat exposure are getting worse and need immediate attention. Now is the time for more resources, standards and agency oversight to ensure our loved ones have the protections they need to come home at the end of the day.

It’s an election year and labor rights — especially the right to come home alive an health at the end of the day — should be on top of the agenda.