Hope you all are having a nice holiday. I did.

But, of course, as I wrote earlier this week, there are a few families in Georgia (and all over the country) who aren’t having a nice holiday.

On the other hand, there is a little good news. Very little, but still…

After the deaths of Sebastian Dykes and James Rayburn, two Georgia public employees recently killed on the job, I’ve been trying to contact reporters in Georgia to inform them of the fact that public employees in the state have no OSHA coverage, and that this tragic and mostly unknown omission might be a good thing to report on.

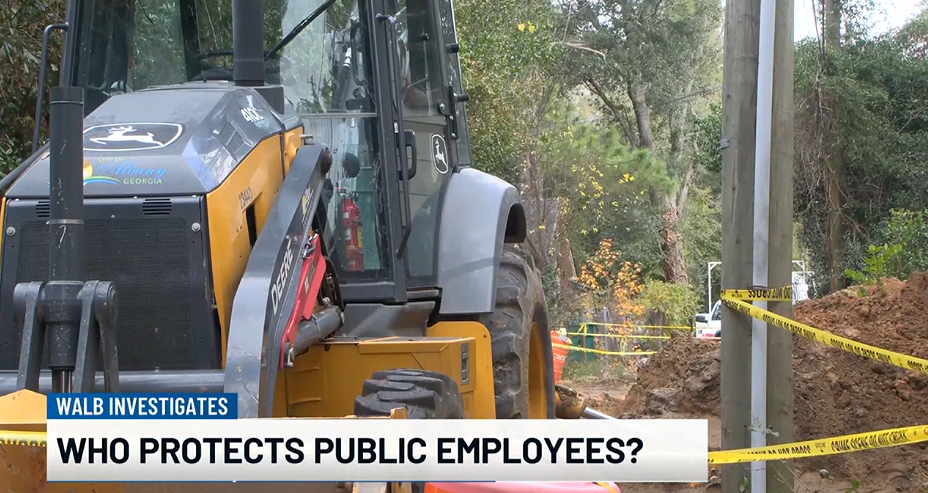

A little progress was made earlier this week with this WALB News story that aired on December 23. WALB Investigative Reporter Lenah Allen looked into public employee safety issues in Albany, Georgia where two of the city’s workers have been killed on the job in the past year.

Allen noted that Albany Mayor Bo Dorough concluded philosophically after the trench collapse that killed Dykes last week, that “Tragic accidents like this do occur…,” and promised that “We will learn from this incident and review our policies and procedures.”

Cities promising to conduct their own “internal investigations” don’t fill me with confidence. Too often these investigations are never conducted, or the results are never released or they simply blame the worker without actually addressing the real causes of the incidents.

She also confirmed the sorry state of public employees in Georgia and 22 other states where OSHA doesn’t have jurisdiction over public workers, a dangerous situation that probably almost no one in Georgia knows.

For that reason, Allen reported, the City of Albany has announced its own internal investigation into Dykes’ death.

As I have written many time before, cities promising to conduct their own “internal investigations” don’t fill me with confidence. Too often these investigations are never conducted, or the results are never released or they simply blame the worker without actually addressing the real causes of the incidents.

Georgia State Personnel Board To The Rescue?

But here’s something new, even to me. Allen was told that there is an agency in Georgia that “protects public employees” — the State Personnel Board — a little known unit that provides rules and policy direction in state employment standards.

Who knew!

Except that, as Allen explains, the State Personnel Board does not investigate work related deaths or inspect work environments.

And checking the Personnel Board’s website, it’s clear that workplace safety is mentioned in none of the almost 40 rules “enforced” by the Board, nor the eight Statewide HR Policies,

And even if they had rules that applied to public employee safety, the State Personnel Board’s rules — even if they included health and safety rules, which they don’t — only apply to state agencies, not cities or counties.

Recordkeeping is nice — and important — but simply cataloguing the injuries and deaths of Georgia’s state employees does nothing to “protect” them.

So what exactly does the Board do to “protect” public employees?

“Similar to OSHA,” Allen reports, “the Board requires all employers to report injuries and fatalities immediately.” In FY 2024 (ending June 30, 2024), the Board reports that 3400 State of Georgia employees were injured, 980 seriously enough to lose a week of work. And six state of Georgia workers were killed on the job.

These numbers only cover state employees, however, so it’s unclear how many county or city employees were injured or killed across the state in FY 2024.

Well recordkeeping is nice — and important — but simply cataloguing the injuries and deaths of Georgia’s state employees does nothing to “protect” them.

To their credit, if you drill down far enough in the Personnel Board’s parent agency, the Department of Administrative Services, you can find the Human Resources Administration that has a “Risk Management” page that offers health and safety fact sheets and training modules on preventing slips, trips and falls; ladder safety, smoke detectors and other issues. Nothing on trench safety or what workers are supposed to do if their employers are not following the suggestions in the fact sheets.

Allen’s story concludes that families who aren’t satisfied with the city’s “internal investigation” still have one option: “They have to hire their own private investigator, which can be extremely expensive.”

Expensive, pretty much impossible (because they’d need access to the site, they’d need to interview workers and city officials and have access to of the cities internal records), and what would they do with the information they gained, especially since workers compensation laws generally prevent workers from suing their employers over health and safety issues or workplace injuries?

Anyway, no grieving family should be left with the responsibility or costs of investigating the death of a family member.

To their credit, Allen announced that WALB will continue to pursue this story, and will follow up on the city’s investigation and file an information and documents request under the state’s Open Records law. I’m looking forward to it.

What Was Missing?

Unfortunately, Allen’s story missed the most important action item of this story: States that don’t currently cover public employees have the option, under the Occupational Safety and Health Act, to pass laws that create an OSHA Public Employee-only program. The program would set up a state OSHA program that would cover public employees in the state, while the feds would continue to enforce OSHA standards for the private sector. Federal OSHA funds 50% of those programs.

Georgia’s FY 2024 Report also noted that injuries and fatalities of Georgia state employees “will end up costing the State of Georgia over $51,000,000.” Sounds like setting up am effective state program would pay off very quickly.

Six states (Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York) have public employee only programs, and twenty-one states have full OSHA state programs that are also required to cover public employees.

But in 23 other states, public employee, who do much of the same work that private sector employees do, have no legal right to a safe workplace. When a worker is killed or serious injured, there is no independent inspection, no citations when employers are found not to have complied with OSHA standards, and no penalties for injuring or killing a worker — as long as they are public employees.

Without a real independent investigation by objective investigators, it is unclear from news articles what caused the drowning of Darrious Stephens last February while taking water samples from the river during heavy rainfall. Nor is it not completely clear what kind of “equipment failure” caused the apparent electrocution of Eric Weems, a lineman working for the city of Griffin, Georgia.

These workers weren’t protected by OSHA’s excavation and trenching standards. Because the law in Georgia and 22 other states don’t consider them to be actual human beings deserving to come home alive at the end of the shift.

But both Rayburn and Dykes were killed in trench collapses. And with all due respect to the Mayor, these tragic deaths do not just “occur.” They are caused by management’s failure to provide safe working conditions and comply with basic safety standards.

I appreciate his desire to “learn from” Dykes’ death, and “review our policies and procedures,” but it’s pretty damn clear why they were killed. We see it all too frequently: The trenches were too deep and weren’t protected against collapse by trench boxes or shoring — two very clear measures mandated by OSHA excavation and trenching standards.

But, of course, these workers weren’t protected by OSHA’s standards. Because there law in Georgia and 22 other states don’t consider them to be actual human beings deserving to come home alive at the end of the shift.

What Is To Be Done to Protect Public Employees?

If anything is to be done to respect the work and the lives of Georgia’s public employees, the state legislature and Governor must move beyond thoughts and prayers and create a public employee OSHA program that will actually have the teeth, resources and enforcement power to protect the lives of state’s, state, county and city workers.

To make this happen, more journalists like Lenah Allen need to cover this story. But they need to go further than Allen’s first piece went. They must reveal that the State Personnel Board has no clothes, that families conducting their own investigations is impractical — and that there is a path for state legislators to take that will provide the protections that the workers who take care of peoples roads, water, garbage, sewage, power and parks deserve.

And then the public employees of Georgia, as well as labor union, public health and worker advocates and others need to organize to demand that the state legislature and the Governor take action to set up an agency that can actually enforce safe working conditions.

Thoughts, prayers and internal investigations aren’t enough.

Thanks Jordan for raising these important issues. FYI – I’ve been involved in some follow up on the Arizona fatality mentioned in the same post as the Georgia incident. A construction worker died after a fall at VAI Resort on Monday morning. Investigators have identified the man as 22-year-old Tyrone Tyre Wilson in Glendale AZ. This is billed as the largest resort construction site under a company Fisher. ABC 15 news in Phoenix area has been reporting on this tragic death. There are several you tube video updates including interviews with family members. The coverage of workplace fatalities has gotten greater attention since reporting starting several years ago involving 2 workers killed in a trench collapse. ABC news is planning to do more on the Wilson story. I’ll post any updates. Thanks