Enough with the current Trump-induced catastrophes engulfing the nation and its working people. Let’s go local and talk about an age-old problem.

Travel with me back to Albany, Georgia, where — as you may remember — two city workers have been killed on the job last year. Georgia, you may recall, is one of 23 states where public employees are not covered by OSHA. State, city and county managers have no requirement to comply with OSHA standards, train workers, or investigate any injuries or deaths.

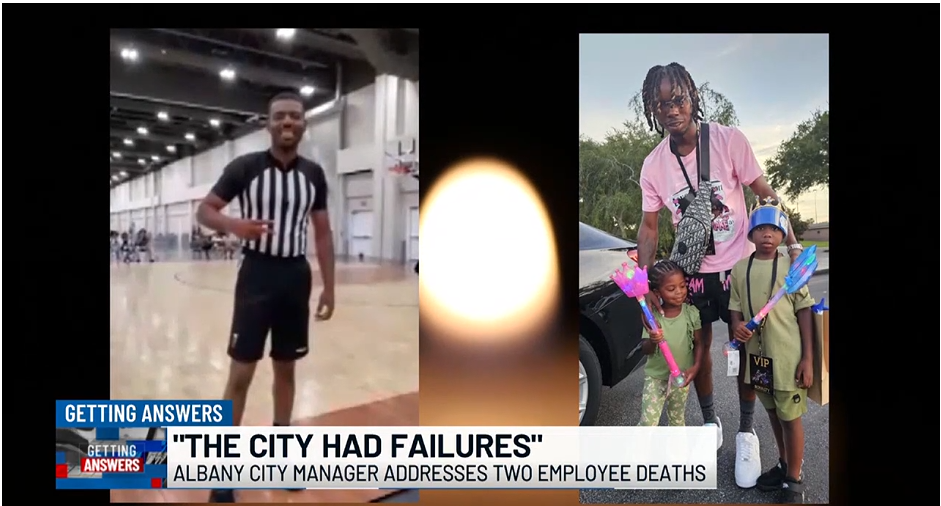

Intrepid WALB news investigative reporter Lenah Allen, who fearlessly reports from Albany, continues to doggedly pursue the reasons behind the recent deaths of Darrious Stephens and Sebastian Dykes Jr. who were killed in preventable workplace incidents. Stephens died on February 24, 2024, while trying collecting water samples from the Flint River, and Dykes died on December 18, 2024 after he was crushed to death in a collapsed trench. Lacking any OSHA investigation, the city of Albany has promised to investigate the two deaths itself.

Allen recently received the city’s Incident Reports about the deaths. One report confirmed that there wasn’t a trench box on the scene where Dykes died.

The incident report revealed that Stephens was reported missing 19 days before his remains were found. It states the employee who was supposed to be with Stephens while he was collecting samples told first responders that “usually one person stays inside the truck so paperwork doesn’t get wet while the other gets out and goes down to the river with a bucket and rope to get the samples.”

Albany City manager Terrell Jacobs admitted Wednesday the city had no standard operating procedures in place at the time Stephens died. He also shared that during Sebastian’s deadly accident, a trench box was not used or on the scene while the employees were deep inside the trench that eventually collapsed on tope of Dykes.

Allen reported that Albany City manager Terrell Jacobs admitted Wednesday the city had no standard operating procedures in place at the time Stephens died. He also shared that during Sebastian’s deadly accident, a trench box was not used or on the scene while the employees were deep inside the trench that eventually collapsed on tope of Dykes.

Allen also interviewed Jacobs. That interview teaches us a few lessons.

Jacobs began by admitting the obvious:

There was probably some issues of that site that we should have reconsidered and thought through. Pretty much it was a failure to address some things that we should have looked at a little bit more closely.

And in regards to the previous incident, I think it was Feb 12, obviously we did not have any SOPs [Standard Operating Procedures] in place at that time. And that’s a failure on our part.

But his statement then gets a bit more problematic when Allen asked “him how many more city employees have to die before the city of Albany protects its employees.” Here there is something to learn for everyone concerned about workers safety.

“Sometimes you don’t know where you have problems until they happen”

Jacobs acknowledged that the trench had safety issues: It was too deep, there was water in it, and there was a gas line nearby. He admitted that it probably wasn’t a good idea to assign city workers to the job.

He added, “Once again, I want to make it clear, we have had failures and in regards to certain areas. And the tragedy of failures is sometimes you don’t know where you have problems until they happen.”

So what’s the problem with this statement?

First, it’s true that “sometimes you don’t know where you have problems until they happen.”

But that’s not good enough. When it comes to workers’ lives, you don’t want wait until tragedies happen. You don’t want to just learn from experience — in this case the experience of two workers’ deaths.

That’s why we have OSHA safety and health standards that incorporate centuries of experience with workplace hazards so that every employer doesn’t have to re-invent the safety wheel from scratch. Mandatory OSHA standards and training ensure that employers — and workers — recognize the problems — and the solutions — before something happens.

“Hold those accountable”

When asked about his message to the families, he responded that “We are at the point where we gotta do right by them by holding those accountable, and number 2, doing better. was that “We’re going to determine who should be held account.” To that end, Allen reported that the city police department is doing an internal investigation into their deaths to determine who will be held accountable. [emphasis added]

What’s wrong with hold the responsible parties responsible? I mean, find the guy who ordered the workers into the trench and fire him. Problem solved, right?

Not quite.

First, there really is no mystery about who is ultimately responsible for these tragedies. And you don’t need a Confidential Informant to solve the crime. Ultimately, it’s not some city supervisor. To find the real perpetrators, you need to look about 200 miles north of Albany to the Georgia State Capitol and Governors’ mansion. Why, you ask?

To find the real perpetrators of these deaths, you need to look about 200 miles north of Albany to the Georgia State Capitol and Governors’ mansion.

Public employees in Georgia and 22 other states are not covered by OSHA, which means they have no legal right to a safe workplace. But the Occupational Safety and Health Act gives states the ability to pass laws that provide OSHA coverage to public employees. OSHA coverage would likely have meant that Stephens and Dykes would be alive today. The city would have been required to train its workers about trench safety and provide a trench box to protect them from a trench collapse.

The failure to provide OSHA coverage to public employees in Georgia lies at the feet of the Governor and state legislators who could pass a law tomorrow that would protect public employees like Darrious Stephens and Sebastian Dykes Jr. (as well as James Rayburn, a Rome, Georgia, city water employee who was crushed to death on December 6, 2024, when a trench collapse on top of him.)

Now, you may argue, plenty of workers — both public sector and private — die even when they’re covered by OSHA. This is true.

But first, far more die on the job than when there are no OSHA standards. Second, even for those who die, despite being covered by OSHA, there is an investigation that identifies the reasons for the incident, and the lessons that should be learned.

There are citations. There are penalties. And for larger cases, there are press releases. All of which send a message to employers in the geographic area and same industry that OSHA is on the job, and you will pay for violating the law.

But there is another problem with just “holding someone accountable.”

So suppose you identify the workers’ supervisors as the culprits, and then discipline or fire them. Does that solve the problem? Unlikely. The city manager admitted there were no SOPs that could have protected Stephens, and there were no applicable standards that protected either Dykes or Stephens. The lack of legal protections or SOPs was the major root cause of their deaths. And just firing the supervisor without addressing those root causes, accomplishes nothing.

Because if you just find a convenient supervisor to scapegoat without fixing the underlying problems, the same thing is going to happen again. And again.

If you just find a convenient supervisor to scapegoat without fixing the underlying problems, the same thing is going to happen again. And again.

If nothing is done to provide OSHA coverage for public employees in Georgia, another public employee will be killed in Albany, or in Rome or in another Georgia city. And then the city manager can yet again say how sorry he is, and yet again explain how they’re going to learn yet another lesson from yet another failure.

The good news is that the city has promised to hire safety officers who will “update the city’s safety policies and assess each department’s personal protective equipment.” That will undoubtedly help — at least in the city of Albany.

But the bad news is that — barring action from the state legislature and Governor — there will still be no law mandating that the city comply with any new safety policies that the new safety officers develop.

Until the Georgia state Legislature and Governor act, public employees in Albany– and in the rest of Georgia — will remain second class citizens without the right to come home alive and healthy at the end of their workday.