One hundred years ago scientists solved a puzzle: how to improve gasoline to make cars more fuel efficient and eliminate “engine knock.” One problem was that additive they used –tetraethyl lead — was toxic. Few tests had been run on the health effects of lead, but after a major scandal at a manufacturing plant in New Jersey where several workers died, the industry devised a plan to obfuscate and deflect attention: create doubt about the danger.

Alice Hamilton, the mother of occupational health in America, having researched the dangers of lead for many years, fought back against the introduction of leaded gas. But she seemed to play a minor role and the push against leaded gas was unsuccessful. It took about 50 years before leaded gas was banned in the United States and another 50 years for a world-wide ban. Meanwhile the oil companies and Ethyl Corporation made millions poisoning the public.

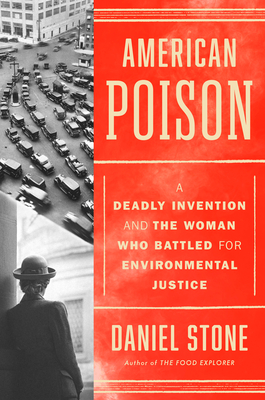

This story is told in detail in a new book by Daniel Stone called American Poison: A Deadly Invention and the Woman Who Battled for Environmental Justice.

This isn’t a new story but the book does offer some insights. The playbook has been used by the cigarette manufacturers, the asbestos industry, the chemical industry, the plastics industry and many others. It was described by former OSHA head David Michaels in his groundbreaking book Doubt is Their Product: A new product is developed. It shows commercial potential. There is also evidence of its toxicity. So rather than do independent research to show the truth and perhaps look for less toxic alternatives, you hire scientists who are willing to obfuscate and parrot the industry line. You create “doubt” about the toxic effects. Chemicals should be “innocent until proven guilty” but the expensive long-term studies that are necessary are never funded. We wait until dead bodies pile up and the evidence is overwhelming before taking any action.

We’ve known about the effects of lead on the body for centuries, since Roman times. And the more we learn, the more toxic we understand it to be. OSHA regulated lead exposures for workers back in the 1980s but the allowable levels were insufficient. Little has been done to revise these limits in the past 50+ years. It was only recently that Cal-OSHA has revised down their allowable workplace limit for lead.

Exposures to the public are even harder to assess and regulate. Towards the end the book points to the excellent work of Dr. Herb Needleman who demonstrated the accumulation of lead in the body by looking at baby teeth. Others contributed pioneering research in the 1960s like Dr. Phil Landrigan who looked at exposures in Boston to people living under the bridge onramps and Dr. Dave Parkinson who saw lead poisoning among residents near a lead smelter in Ontario. Even today, under the new Administration, regulations on air pollution are targeted for “loosening” with claims that “It doesn’t mean a damn bit of difference, either, for the environment. It doesn’t matter.” The recent gutting of the National Institute for Occupational health and Safety (NIOSH) is just going to exacerbate the problem.

This book is a good primer showing the industry playbook and how devastating the impact can be. The author points to Alice Hamilton for inspiration, though her work was primarily in occupational health and her efforts in this case failed. He concludes on the optimistic note that “a single person…can create considerable progress for the good of others.” That’s slim hope in the current atmosphere where science is being undercut left and right and the truth seems dispensable.

For more good reading about workers, workplace safety and health, and the labor movement, check out the Confined Space book list.

Thought the EJ focus brought a new lens to Alice and her legacy as a much broader public health impact. I loved the book and recommend to others! ❤️