In September 2001, I found myself at the World Trade Center (WTC) site as part of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ (NIEHS) initial assessment team. The scale was overwhelming—sixteen acres of twisted steel and concrete dust that hung in the air like fog. We deployed with our standard protocols: monitor, measure, mitigate. Air sampling pumps, particle counters, chemical detection equipment. The dangers were obvious and immediate—airborne particulates, structural instability, chemical exposures from burning materials.

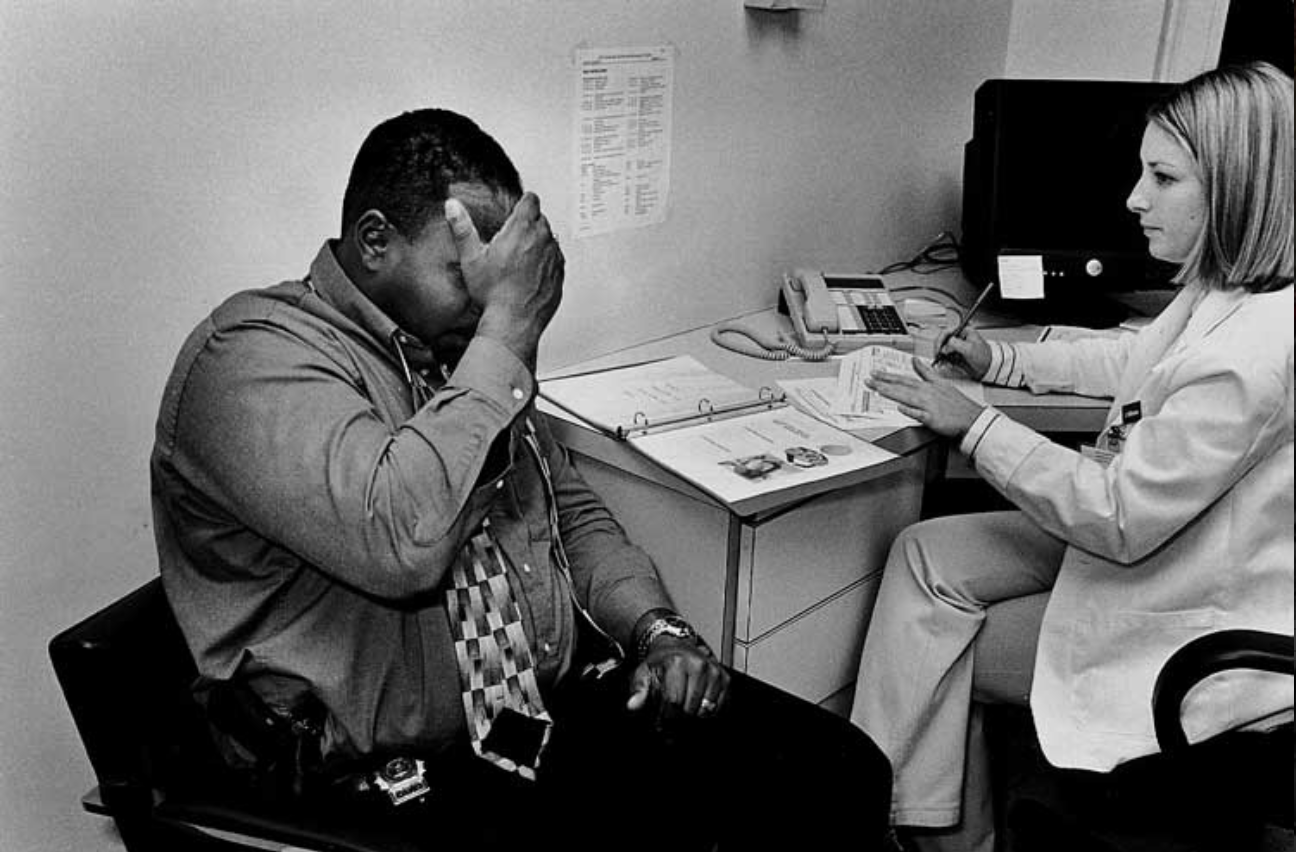

But something else caught my attention in those first days. The “thousand-mile stare” of responders and survivors—that hollow, distant look of people processing the unprocessable. Firefighters who’d worked through the night, construction workers volunteering their time, emergency medical teams rotating through twelve-hour shifts. They moved with purpose, but their eyes told a different story.

Early in my career, mental health in the workplace was rarely acknowledged in occupational safety circles. We had industrial hygienists, safety engineers, toxicologists. Mental health was someone else’s department—if it was anyone’s department at all. The assumption was simple: tough jobs require tough people. Deal with it.

The WTC response shattered that assumption. Over the following months and years, as we tracked the health impacts on cleanup workers, the psychological toll became undeniable. Depression rates soared. PTSD diagnoses multiplied. Suicide rates among first responders began climbing—and they haven’t stopped climbing.

This recognition deepened during the opioid crisis, which laid bare the inseparability of mental and physical health in worker wellbeing. Workers in pain—physical or psychological—were self-medicating. The pills that started as legitimate treatment for workplace injuries became pathways to addiction and death.

When COVID-19 hit, our profession faced another test. In March 2020, I began hosting Friday calls with trainers, frontline responders, and safety professionals nationwide. These weren’t just technical briefings about PPE shortages or decontamination protocols. We combined real-time hazard updates with something less tangible but equally important: guided group meditation.

It sounds unconventional—maybe even soft—for a field built on hard science and harder realities. But creating that virtual “sacred space” for shared reflection became a healing practice for many participants. People logging in from hospital break rooms, fire stations, construction trailers. Taking ten minutes to breathe together, to acknowledge the weight they were carrying.

Resilience, we learned, is a communal act.

Mental Health as Core Occupational Safety

The lesson from 9/11 through COVID is clear: we cannot separate mind from body in disaster response. This isn’t about being compassionate—though we should be. It’s about being effective. Psychological injuries disable workers as surely as chemical exposures or falls from height.

Redefining Workplace Hazards

We’ve spent decades perfecting our ability to measure physical dangers. Parts per million of benzene. Decibel levels that damage hearing. Ergonomic stressors that cause repetitive strain injuries. We have exposure limits, engineering controls, personal protective equipment.

Psychological injuries disable workers as surely as chemical exposures or falls from height.

But psychological hazards? We’re still learning to name them, let alone control them. Witnessing traumatic events. Working under extreme time pressure with life-or-death consequences. Isolation from family and normal support systems. Moral injury—the psychological damage that occurs when workers are forced to act against their values or witness preventable harm.

These aren’t character flaws or signs of weakness. They’re occupational exposures that require the same systematic approach we bring to any other workplace hazard. Assessment, controls, monitoring, treatment.

The Stoicism Problem

First responder and cleanup cultures prize toughness—and for good reason. Lives depend on people who can function under extreme stress, who can compartmentalize horror and keep working. But that same stoicism becomes a barrier to help-seeking when the immediate crisis ends.

“Suck it up.” “Others had it worse.” “I signed up for this.” These aren’t just personal attitudes—they’re organizational cultures that can be as toxic as any chemical we regulate. When seeking mental health support feels like professional suicide, workers suffer in silence until suffering becomes unbearable.

We’ve seen this pattern repeatedly. After 9/11, many cleanup workers delayed seeking help for years. Some never sought help at all. The statistics are stark: more first responders have died by suicide since 9/11 than died in the towers themselves.

Early Intervention Saves Lives

In occupational health, we don’t wait for workers to develop silicosis before addressing dust exposure. We don’t wait for hearing loss before implementing noise controls. The same logic must apply to psychological health.

Early intervention means recognizing that exposure to traumatic events, chronic stress, and moral injury will have psychological consequences for some percentage of workers. Not everyone, but enough that we need systematic approaches to identification and treatment.

In occupational health, we don’t wait for workers to develop silicosis before addressing dust exposure. We don’t wait for hearing loss before implementing noise controls. The same logic must apply to psychological health.

This requires shifting from reactive to proactive mental health support. Psychological first aid training for supervisors. Regular check-ins that go beyond “How are you holding up?” Embedded mental health professionals who understand the work culture and can provide intervention before crisis points.

Peer Support as Infrastructure

Workers trust other workers. They’ll tell a fellow firefighter things they’d never tell a supervisor or a counselor. This isn’t a flaw in formal mental health systems—it’s an opportunity.

Peer support programs, when done well, provide the first line of intervention. Trained peers can recognize warning signs, provide initial support, and connect colleagues to professional resources when needed. They speak the language of the work. They understand the stakes.

But peer support can’t be an add-on or an afterthought. It requires training, ongoing supervision, and integration with broader mental health resources. Peers need to know their limits and when to refer up the chain.

Community-Centered Response

Local communities affected by disasters bring their own trauma to the response. The same explosion that injured workers devastated neighborhoods. The same flood that created cleanup jobs destroyed homes and schools.

Community engagement in disaster response must include emotional wellbeing. This means mental health professionals at the unified command level, not just occupational health specialists. It means recognizing that community resilience and worker resilience are interconnected.

When communities feel heard and supported, the overall response environment becomes less stressful for everyone involved. When communities feel ignored or endangered by response activities, tensions escalate and psychological stress multiplies.

Training the Whole Person

Site-specific safety training that ignores the emotional impact of disaster work leaves responders vulnerable. A worker who knows how to don PPE correctly but doesn’t know how to process what they’re seeing through that faceplate is only partially protected.

This doesn’t mean turning safety briefings into therapy sessions. It means acknowledging that psychological preparation is part of physical preparation. Teaching workers what to expect emotionally. Normalizing stress reactions. Providing tools for self-care and peer support.

Site-specific safety training that ignores the emotional impact of disaster work leaves responders vulnerable. A worker who knows how to don PPE correctly but doesn’t know how to process what they’re seeing through that faceplate is only partially protected.

It means creating space in the work environment for workers to process difficult experiences. Structured debriefings. Shift rotations that prevent burnout. Communication protocols that allow workers to express concerns without fear of being removed from the job.

The Path Forward

Twenty-three years after 9/11, we’re still learning these lessons. The field of occupational safety and health has evolved, but too slowly and often only after preventable tragedies.

We need mental health professionals embedded in disaster response from day one. We need psychological safety standards as detailed as our chemical exposure limits. We need organizational cultures that treat help-seeking as a sign of professionalism, not weakness.

Most importantly, we need to understand that protecting worker mental health isn’t separate from protecting worker physical health—it’s the same mission. A worker disabled by PTSD is as lost to the workforce as one disabled by lung disease. A suicide is as preventable as a fall from height.

The thousand-mile stare I saw at Ground Zero was a warning sign we didn’t know how to read. We’re learning to read it now. The question is whether we’ll act on what we see.

Thank you for this very important message. In light of recent events, we all need support of community. That’s a strength, not a flaw.