This is always the saddest part about ushering in the New Year: remembering the health and safety and environmental activists that we’ve lost over the last 12 months.

All of the people listed below are heroes and they are all missed. But all of them passed with the knowledge that — because of their work, their passion and their contributions — they saved lives. Most of the workers whose lives they saved or injuries and illnesses they prevented have never heard of them and don’t know their work. And maybe that’s as it should be. Because as we esteemed elders begin to look back and sum up our lives, there’s no better legacy than the knowledge that our work saved lives and made the world a little better place to work and live. And that’s enough.

May their memories be a blessing and an inspiration to fight on.

Azita Mashayekhi

Azita Mashayekhi died on July 13 at age 61. Azita was a industrial hygienist in the Teamsters Safety and Health Department for over 30 years, and a long-time colleague and friend of those of us in the national health and safety community. Azita was famously energetic and curious and creative, focusing on not just the main issues that her Teamster members faced but hazardous jobs your rarely think about. My inbox is littered with questions from her looking for information on hazards impacting cemetery workers, employees working overtime, parking attendants and others.

Azita, who moved to the United States at age 18 after Iran’s 1979 revolution, was also an amazing photographer, displaying in the Washington DC area. She was also instrumental in installing a colorful mural on the wall outside the Community for Creative Non-Violence, a Washington D.C. homeless shelter near Teamster headquarters. For her, the need was obvious. “It’s just a bad scene. I just thought we could use some color.”

Former OSHA head David Michaels recalled that “Azita was a very spirited advocate, with a memorable smile and way to convince you to help with whatever she was working on.” Her National COSH co-conspirators remembered that “Azita fought tirelessly for safer workplaces, bringing energy, joy, and determination to the fight. Even after retirement, she stayed connected through the COSH Advisors, finding ways to support and uplift others. Her legacy lives on in the lives she touched and the workers she protected.”

National COSH Director Jessica Martinez remembers how at COSHCON’s awards night she brought light-up headbands, passing them around with the biggest smile, leading the room in song and dance. “That was Azita: making serious work lighter and reminding us to celebrate each other.”

Leo Gerard

Former United Steelworkers President Leo Gerard died on September 21 at the age of 78. Leo was President of the United Steelworkers from 2001 to 2019 and workplace safety and health concerns were center in his long career. He grew up in the town of Sudbury, Northern Ontario, site of a huge complex of smelters and mines extracting and refining nickel and other metals. His father was a union activist for the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, which became part of the Steelworkers. A close friend from those days remembers Leo as a child, hearing sirens whenever a worker was killed or badly hurt, not knowing whether it was his dad. “He wanted those sirens stopped, and he saw the union as the only way to stop them.”

At age 18, Leo followed his father into the industry and union activism, beginning his career unclogging air pipes at an Ontario nickel smelter. Health and safety concerns were central in the dangerous mines and smelters. He was elected area steward at age 22 and chief steward at age 26 where he worked closely with the safety committees to grieve unsafe conditions, defend workers who refused to work in unsafe conditions and those falsely accused of safety violations in order to cover up the company’s negligence.

Leo later spent much of his time as USW staff representative in Northern Ontario working on health and safety issues. He worked with uranium miners, including a failed attempt by the Canadian federal government to revise radiation standards. After becoming Canadian National Director (and International Secretary Treasurer), he led the union response to the 1992 Westray Mine Disaster, which killed all 26 miners. The USW had been organizing the mine at the time, and even though the mine would never reopen, it became a USW local so that the union could assist and represent the remaining miners and the families of those killed in all the subsequent legal battles. Under Leo’s leadership, the union waged a decade-long fight for a law criminalizing corporate negligence leading to a workplace death or serious injury. The legislation, called the Westray Bill, finally became law in 2004.

As union president, Leo helped strengthen and improve the USW Emergency Response Team which provides on-site assistance to badly injured workers and the families of those killed in the workplace. Its work complements that of the USW Health, Safety and Environment Department, which investigates, on-site, nearly every fatality and many serious accidents. Leo always saw safety and health as a global issue, helping to found the world’s first global union-management safety and health committee at ArcelorMittal. He also led the Steelworkers to create the BlueGreen Alliance, a partnership with the Sierra Club, to push for cleaner manufacturing.

On a personal note, I talked with Leo many times at USW conferences and meetings. You meet a lot of union Presidents and politicians in my line of work. he never had to be convinced that workplace safety and health issues were important. You could always tell that Leo “gets it” and held the firm belief that keeping members alive and healthy needed to be one of the core elements of unionism. We need more like him.

(Thanks to former USW Health and Safety Director Mike Wright for most of this.)

Bob Alvarez

Bob was a long-time advocate for and organizer of workers who suffered from the legacy of the nuclear arms race. I worked a bit with Bob in the late 1970s when he was working for the Environmental Policy Institute, research nuclear waste and advocating for compensation for former uranium miners and nuclear workers who were suffering from cancer and various other serious diseases from their on-the-job exposures throughout the Cold War. He was shocked to discover that no one really knew or cared about these workers:

The nuclear weapons industry was largely exempt from federal oversight. Contaminated water was often poured into streams and lakes. Storage containers built in the 1950s were starting to leak.

“Basically you had a system that was deliberately set up under conditions of secrecy, isolation and privilege where they weren’t accountable to anyone but themselves,” he told NPR in 2000.

In the 1980s, he worked for Ohio Senator John Glen where he confronted the Atomic Energy Commission and Department of Energy DOE who were holding back information on the health effect suffering by nuclear workers. Bob’s work led to the agency’s agreement to finally to share its data and provide funding to NIOSH for independent scientists to conduct epidemiologic studies on DOE workers. He also helped build the case for the massive environmental cleanup program necessary to remediate the decrepit and ultra-hazardous conditions that endangered workers and the communities in Ohio and across the weapons complex. He helped enact legislation in 1988 that created the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board which put a (largely unenforceable) check on the worst of the DOE’s reckless pursuit of production ahead of safety. Bob later worked for six years as a senior adviser in the Department of Energy under Bill Clinton’s Energy Secretary Bill Richardson, where he worked with then Assistant Secretary of Environment, Safety and Health, David Michaels, to build the case for passing a federal compensation program for atomic workers, a goal that had repeatedly eluded the unions and attorneys representing sick workers since the 1950s.

Former workplace safety and health advocate Richard Miller, a close friend and coworker of Bob and his wife Kitty Tucker (who was also a worker and environmental advocate), wrote that “Breaking the AEC/DOE monopoly of radiation effects research unlocked government secrets and finally enabled credible research. Bob’s fingerprints are all over the efforts to unravel the web of secrecy and insularity that bred scientific corruption. His legacy—inside and outside of government—has had a lasting impact on the lives of many who never met him or will ever know his name.”

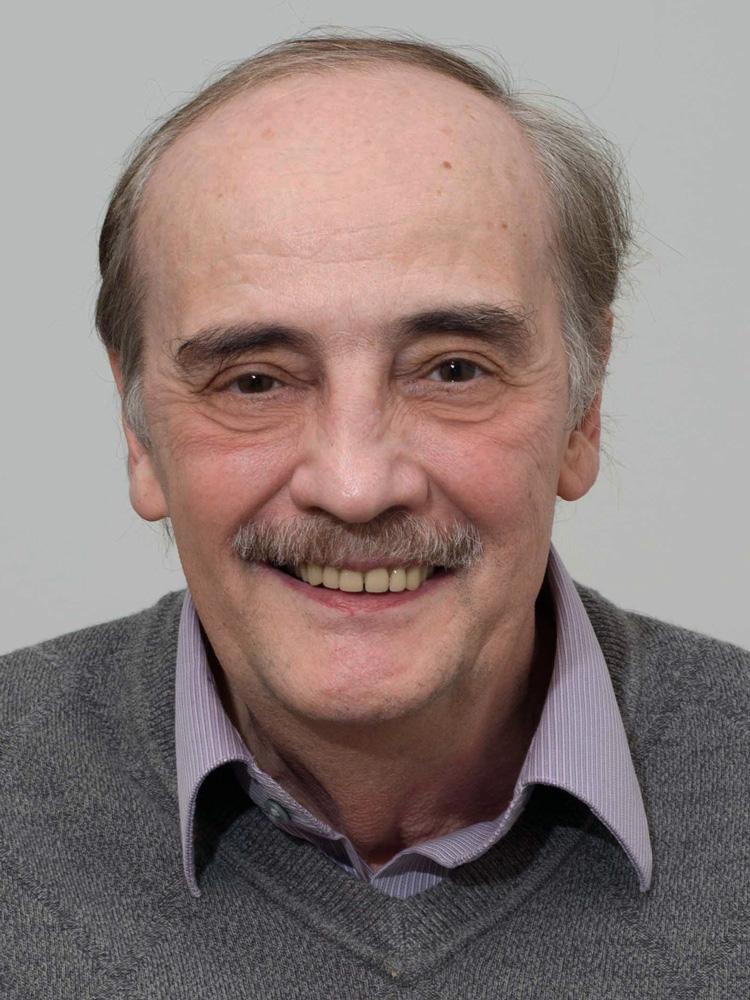

Sheldon Samuels

For those of us who started off in the workplace safety and health field in the 1970s and 1980s, there was almost no one more supportive than Shelly Samuels. He was always smiling, friendly and willing to help — and accompanied that help with tons of fascinating stories. Shelly was Director of Health, Safety and Environment for (now defunct) Industrial Unions Department of the AFL-CIO, and Special Representative for Nuclear Weapons Workers Health of the Metal Trades Department.

He was one of the few leaders still alive who was present at the creation of OSHA:

In 1971 he was recruited by the industrial unions to develop the labor movement’s first education and research center for occupational and environmental health. He personally submitted the first petition for the first permanent standard under the OSHAct – for asbestos – and coordinated subsequent successful petitions for benzene, cotton dust, lead, vinyl chloride, carcinogens, sanitation, medical surveillance, radon daughters, and other standards issues. He conducted pilot industry-specific educational and research programs for the international labor movement such as “Superfund” workers training and authored the AFL-CIO policies on genetic testing and medical surveillance.

And he understood the politics of worker protection and the reasons for industry opposition to the existence of OSHA: ”A worker for the first time has legal access to his own medical records. All this is driving management up the wall because it amounts to worker participation in an area where management believes it has the sole prerogative.”

Shelly was one of the founders of the Workers Institute for Safety and Health (WISH) which was critical to my education when I joined AFSCME in 1982 and knew nothing. He also created the Workplace Health Fund to demonstrate that research, when formulated from the perspective of workers, could have very different results from traditional research framed industry or by academic elites. The last time I saw him was on a panel at the American Public Health Association conference in 1998 on a panel with Tony Mazzocchi and Eula Bingham. (For those of us in the health and safety field, it was similar to a panel American history featuring George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin.) Shelly passed away in November at age 96.

Kent Wong

Kent Wong, former director of the UCLA Labor Center from 1991-2023 and professor of labor studies and Asian American studies, died Oct. 8 at age 69. As director of the UCLA Labor Center for 32 years, Kent was renowned across Los Angeles and the nation for his labor and immigrant rights advocacy and his fierce dedication to undocumented communities. He focused on popular education, co-editing with former UCLA Labor Occupational Safety and Health (LOSH) Director Linda Delp “Teaching for Change: Popular Education and the Labor Movement” which focused on the the role of education in movements for worker and workplace safety and health rights.

According to his obituary, Kent played a pivotal role in creating multiple major equity-focused organizations. In 1992, he founded the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA), AFL-CIO, the first and only national organization of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander workers. Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass remembered how “Kent understood that Los Angeles’s strength lies in its working people. ” He was a mentor to thousands of young people.

Staff at the UCLA Labor Occupational Safety and Health (LOSH) Program remembered how Kent deeply understood the connection between worker health and social justice. He saw the fight for safe and healthy work as inseparable from the broader struggles for workers’ rights, dignity, and respect. Linda Delp remembers Kent as a “fierce advocate and internationally recognized labor activist and educator, with the vision to connect worker rights with immigrant rights, the right to unionize and to fight for health and safe working conditions.” She called him a “strategy wizard” for his ability to secure funding to expand university-based labor and workplace health and safety centers in California.

Both of Wong’s grandmothers, who were born in the U.S., lost their citizenship when they married male Chinese nationals — the impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which went into effect in 1882. “He saw how citizenship is often a weapon used to divide communities and divide families,” his son Ryan said. Early in his career, Wong was the staff attorney for a local chapter of the Service Employees International Union. He served as the founding president of the United Assn. for Labor Education, and a vice president of the California Federation of Teachers. When President Trump sent armed federal immigration agents into Los Angeles, Wong was shocked and spent the summer vigorously organizing training sessions for more than a thousand workers and union organizers to peacefully protest the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant communities.

Susan Michaelis

Susan Michaelis was a former Australian flight instructor and airline transport pilot with over 5,000 flying hours who became internationally recognized as a an aviation health and safety consultant and PhD researcher in the field of safety in aircraft contaminated air supplies and hazardous substances.

Hers was a fascinating story:

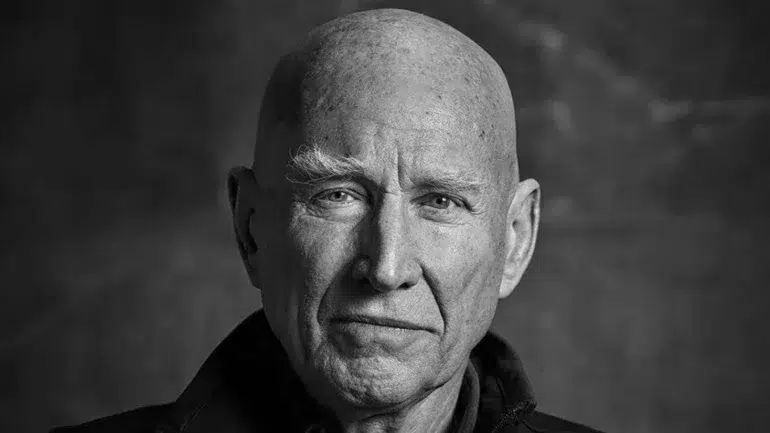

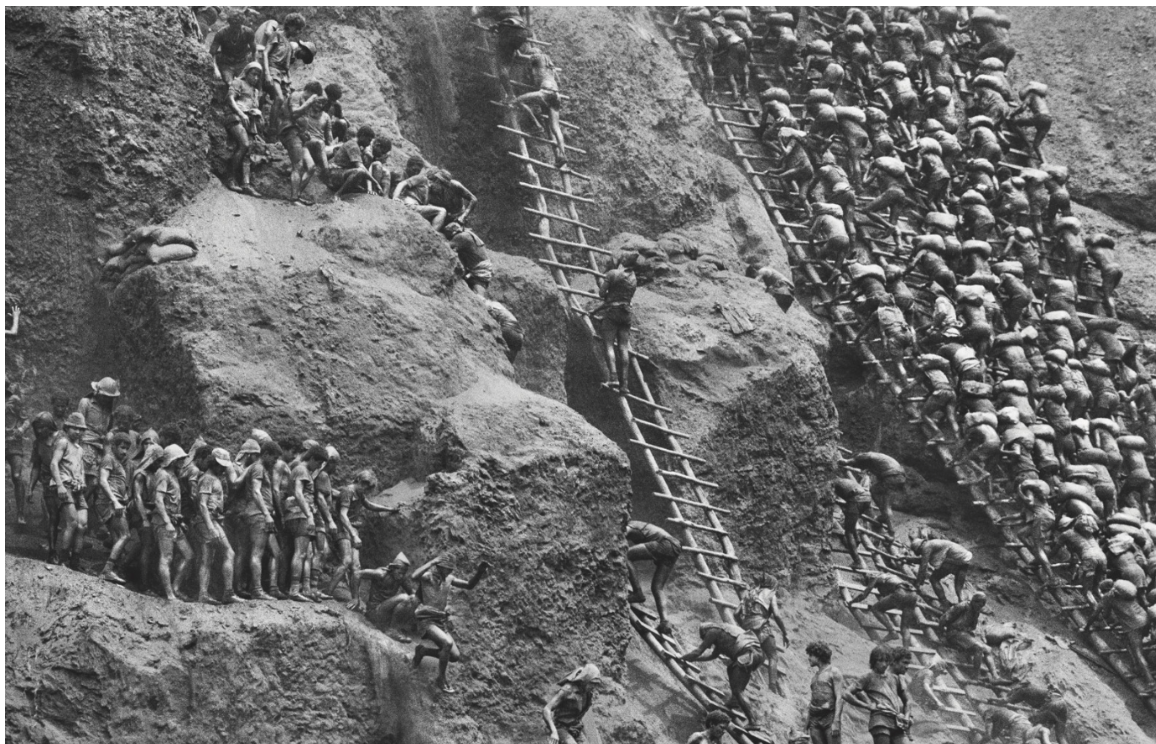

Sebastião Salgado

Salgado was a Brazilian photographer who focused on recording workers in dangerous jobs. Salgado produced a number of extended documentary series including Sahel: L’homme en détresse (1986), Other Americas (1986), An Uncertain Grace (1990), and Workers (1993), a worldwide investigation of the increasing obsolescence of manual labor. He captured some of his most well-known images in 1986, of workers toiling in a gold mine in the northern Brazilian state of Pará.

Sebastião Salgado’s straightforward photographs portray individuals living in desperate economic circumstances. Because he insists on presenting his pictures in series, rather than individually, and because each work’s point of view refuses to separate subject from context, Salgado achieves a difficult task. His photographs impart the dignity and integrity of his subjects without forcing their heroism or implicitly soliciting pity, as many other photographs from the Third World do. Salgado’s photography communicates a subtle understanding of social and economic situations that is seldom available in other photographers’ representations of similar themes.

Salgado died last May at age 81. He was somewhat controversial:

He was at times criticized for cloaking human suffering and environmental catastrophe in a visually stunning aesthetic, but Mr. Salgado maintained that his way of capturing people was not exploitative.

“Why should the poor world be uglier than the rich world?” he asked in an interview with The Guardian in 2024. “The light here is the same as there. The dignity here is the same as there.”

Thank you for this column

I worked with both Leo and Azita and considered them friends as well as colleagues. Azita s death hit me particularly hard, as we stayed in touch after I retired. I went to see her on my last day at AFSCME. She was a light.

Thank you for doing this Jordan. You not only honor their work, you remind us of their critical contributions toward keeping workers safe and healthy.

Thank you Jordan. Love the early photo of Sheldon. He was one of my mentors. And also introduced me to my love of sailing on his boat on the Chesapeake in southern Maryland. Great memories.