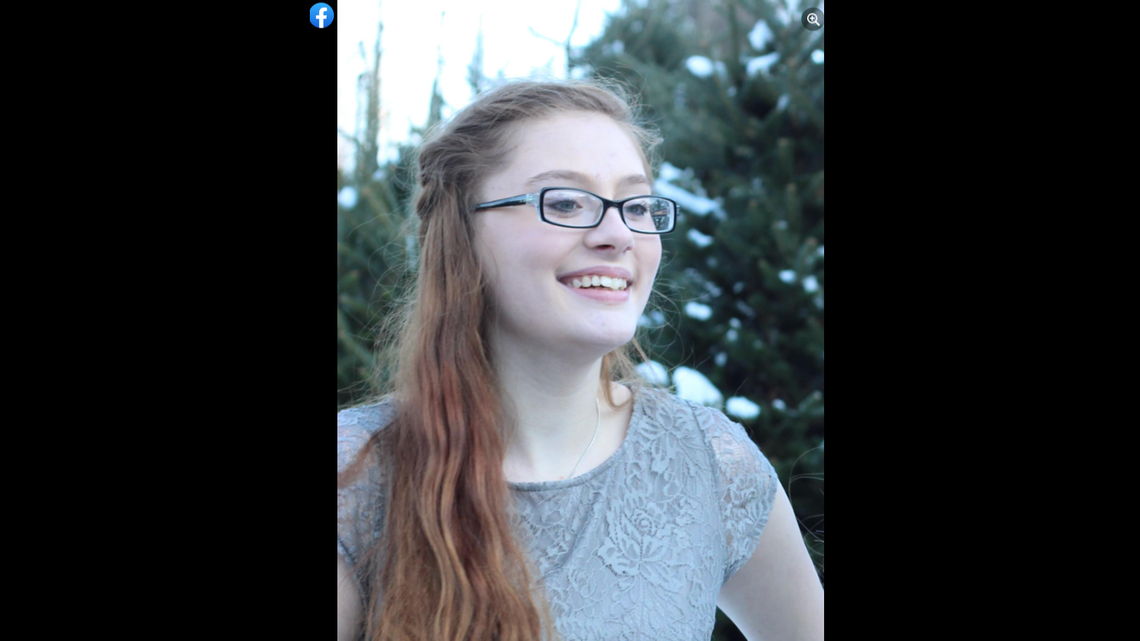

Late on the night of June 2, 23-year-old Tava Woodard was killed in a robbery at the Roadrunner convenience store at a gas station in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Anyone reading the Weekly Toll can’t help but notice that Woodard’s killing was not an exception. Every week, there are at least half a dozen workers who are shot and killed (or sometimes beaten to death) in convenience stores and gas stations — usually working alone at night. Add to that a delivery driver, taxi driver or ride-sharing services or two who get killed every week or so. 21% of all workplace homicides occur in the sales and related occupations. 50 gig workers murdered or killed on the job since 2017, according to a recent report from Gig Workers Rising.

And because the Weekly Toll is only able to pick up those cases that appear in the media, non-fatal assaults and injuries remain mostly invisible. The Department of Justice reports that only 46% of nonfatal workplace violence against workers in retail sales occupations was reported to police in 2019.

What can be done to protect these workers?

Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA?

Unfortunately, most convenience story murders are simply turned over to the police as a criminal matter and OSHA rarely takes any action to cite employers. There’s a general assumption that, hey, it’s just bad guys. It’s a police matter. OSHA has no workplace violence standard, leaving the agency’s General Duty Clause -as the agency’s only enforcement tool.

The General Duty Clause requires there to be a “recognized hazard” and a “feasible means of abatement,” so if employers can reasonably claim they had no idea their store was at risk of robbery, or that there’s nothing the employer can do to prevent robberies, then OSHA’s hands are tied.

But retail establishments should not be getting off that easy. Violence in retail establishments is a recognized hazard –especially late night retail — and the above-there are well-recognized risk factors — like contact with the public, access to cash and working alone, working late nights, as well as a history of crime in the neighborhood.

And there are many feasible actions that employers can take “abate” — reduce or prevent these attacks.

As far back as the late 1990’s OSHA issued Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments. The guidelines were taken from industry standards and include recommendations such as:

- Limiting window signs to low or high locations and keeping shelving low so that workers can see incoming customers and so that police can observe what is occurring from the outside of the store

- Ensuring the customer service and cash register areas are visible from outside the establishment;

- Placing curved mirrors at hallway intersections or concealed areas;

- Maintaining adequate lighting inside and outside the establishment;

- Installing video surveillance equipment and closed circuit TV to increase the likelihood of identification of perpetrators;

- Using door detectors so that workers are alerted when someone enters the store;

- Installing and regularly maintaining alarm systems and other security devices, panic buttons, handheld alarms or noise devices, cellular phones and private channel radios where risk is apparent or may be anticipated;

- Arranging for a reliable response system when an alarm is triggered;

OSHA also has a fact sheet for preventing workplace violence for taxi drivers and has a Compliance Directive that provides guidance for OSHA compliance officers to use the rather unwieldy General Duty Clause to issue workplace violence violations.

And to its credit, despite the difficulty in using the General Duty Clause, OSHA has been putting that guidance to work and using the General Duty Clause to cite employers who fail to protect their workers from workplace violence in retail/general industry.

Last June, CalOSHA cited two employers in Half Moon Bay where a mass shooter killed seven employees last January at a mushroom farm.

Cal/OSHA cited California Terra Garden, Inc. for 22 violations, after a mass shooting where four employees were killed, for failing to have a plan or procedures to immediately notify employees of an active shooter threat and instruct them to seek shelter. Total proposed penalties were $113,800. Concord Farms Inc. was cited for 19 violations, three of them serious, including failure to address previous incidents of workplace violence and develop procedures to correct and prevent the hazard. Total proposed penalties were $51,770.

Last year, OSHA cited the operator of several Baton Rouge-area car wash, oil change, fueling, and convenience store locations after a workplace violence investigation into the stabbing of an assistant manager on Feb. 6, 2022.

Unfortunately, workplace violence citations in the non-healthcare workplaces are few and far between. But even a few small OSHA citations are not going to change the world, they send a message out that violence against retail and transportation workers is a recognized hazard, there are measures that will reduce the risk, and that employers are required to implement measures to make their workplaces safe.

The Avoidable Murder of Tava Woodard

So was the killing of Tava Woodard a tragic, but unfortunately all-t00-normal and unpreventable crime that falls out of OSHA’s jurisdiction? Just a police matter that the employer could never have predicted or prevented?

No.

The emergency alarm button at the store wasn’t working. Nor was the backup alarm. In fact, it wasn’t even hooked up. And no testing had been done:

It turns out that all was not roses and sunshine at the gas station before Tava was killed:

“A couple of her friends have told me that she had texted them that night. That she hated it there and she didn’t feel safe; it was scaring her there lately,” [Tava’s mother, Melissa] Jones told the outlet. “She expressed some concerns as well to coworkers and family, friends. … She expressed some concerns that night.”

The employer, obviously recognizing the risk, had installed an emergency alarm button to alert law enforcement of possible emergencies, as well as a backup alarm. But the emergency alarm button at the store wasn’t working. Nor was the backup alarm. In fact, it wasn’t even hooked up. And no testing had been done:

Employees of the Roadrunner said they have been requesting that this issue be fixed for a while and that the button was fixed after Woodard’s death.

“The gentleman expressed that we were supposed to be testing it on a monthly basis,” said [store employee Joseph] Aguilar. “No prior management that I have spoken with has had that information. No current management I’ve had has expressed that information.”

Former manager, Ashley Griffin, said she was also not aware of the monthly testing.

The OSHA compliance directive states that “OSHA may initiate inspections at late-night retail facilities” when there are violent acts by people who enter the workplace to commit a robbery or other crime. And where risk factors exist, like late night work, exchanging money, working alone, in a high crime area and previous complaints about security.

So given the existing risk factors, a recognized hazard and the failure of the employer to provide to test or repair the broken alarms, the death of Tava Woodard seems like prime territory for OSHA to act. Right?

Not so much.

Tennessee is one of 21 OSHA state plan states that run their own OSHA programs. Tennessee OSHA opened and closed an investigation the same day, finding the employer, GMP Enterprises, “in compliance.”

State plan states are required to run enforcement programs that are “at least as effective” as federal OSHA’s program, and federal OSHA oversees the programs, issuing an annual report on the state plan’s performance. Will Tennessee OSHA’s failure to pursue this case be a subject of federal OSHA’s attention?

We shall see.

OSHA Regulatory Action on Workplace Violence

Federal OSHA has been working on a workplace violence standard since the end of 2016, but it will only cover health care and social service workers — a particularly vulnerable sector. In 2018, for example, health care workers in the private sector filed more disability claims due to injuries from violence at work than people in every other private sector profession combined. Nationwide, 73% of all the reported workplace injuries due to violence happened in health care and social services.

One major factor is understaffing which minimizes the amount of time health care workers have to build relationships with patients and de-escalate difficult situations. Lack of staffing also forces more healthcare workers to work alone, and limits the help they will receive when a patient threatens them.

Because workplace violence is so common in health care workplaces, Federal OSHA has been using the General Duty Clause to cite employers in health care much more frequently than in retail or other industries. Citations are based on OSHA’s revised Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers, but, as mentioned above, the General Duty Clause is a burdensome and legally vulnerable avenue for the agency.

Progress on the OSHA workplace violence standard has been painfully slow. The Trump administration did nothing to move it forward, and COVID sapped much of the agency’s resources at the beginning of the Biden administration. Add to that legal obstacles slowing the regulatory process and resource, and we are unlikely to see a workplace violence standard until the middle of a second Biden term, although the agency is hoping to issue a proposal.

If there is no second Biden term, healthcare workers will continue to get hurt and die with no hope of a protective standard.

The House of Representatives, recognizing OSHA’s regulatory hurdles, passed legislation in 2019 and 2021 that would have directed OSHA to issue a workplace violence standard on an accelerated schedule.

The House of Representatives, recognizing OSHA’s regulatory hurdles, passed legislation in 2019 and 2021 that would have directed OSHA to issue a workplace violence standard on an accelerated schedule. No action was taken in the Senate.

Meanwhile, health care and social service workers remain at high risk. Over the last month, two Oregon health care employees were killed on the job — a mental health employee was murdered at a residential care facility in Gresham and an unarmed security guard was shot and killed in a maternity unit of an Oregon hospital.

Oregon health care workers rallied to demand better workplace violence protections.

Jennifer Suarez, an emergency department nurse at Legacy Mount Hood, took the megaphone.

She told the crowd that nurses rarely get the support they need from managers to protect themselves.

“We’re told, you don’t need to call the police for that,” she said into the megaphone. “They shouldn’t be trespassed for that… It’s part of your job.”

She paused, emotion filled her voice. “Dying or being assaulted is not part of our job!” she called out, to cheers from the crowd.

“Dying or being assaulted is not part of our job!” — Jennifer Suarez, an emergency department nurse at Legacy Mount Hood

And that’s not all:

Last year, a man killed two workers at a Dallas hospital while there to watch his child’s birth. In May, a man opened fire in a medical center waiting room in Atlanta, killing one woman and wounding four. Late last month, a man shot and wounded a doctor at a health center in Dallas. In June 2022, a gunman killed his surgeon and three other people at a Tulsa, Oklahoma, medical office because he blamed the doctor for his continuing pain after an operation.

It’s not just deadly shootings: Health care workers racked up 73% of all nonfatal workplace violence injuries in 2018, the most recent year for which figures are available, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

An Illinois social worker was killed on the job in 2022 and progress has been slow in improving conditions like staffing have not improved. Social workers still suffer from verbal abuse, threats and violence against them.

CalOSHA Workplace Violence Standard and Legislation

CalOSH — unlike federal OSHA — has a workplace violence standard covering healthcare and social service workers, and the CalOSHA Standards Board formed an advisory committee six years ago to began considering a workplace violence prevention standard that would apply to all industries, not just healthcare.

Earlier this year, CalOSHA issued a revised draft workplace violence standard that would apply to general industry. The standard would require employers to establish, implement, and maintain an effective Workplace Violence Prevention Program which would include procedures for responding to a workplace violence emergency.

The employer would also be required to provide training to employees on handling workplace violence and have procedures to identify workplace violence hazards, (including scheduled periodic inspections to

identify unsafe conditions and work practices), procedures to evaluate workplace violence, hazards identified through periodic inspections, employee concerns, workplace violence incidents, and procedures to correct workplace violence hazards in a timely manner. Finally there would also be procedures for post-incident response and investigation. Employers who have not had an incident in the past five years would be exempt from keeping a log of violent incidents.

Unions have complained that the CalOSHA standard-setting process is too slow and are supporting Senate Bill 553, which would bypass the normal regulatory process and enact detailed statutory requirements applicable to all employers. The Senate passed the bill in May and it passed out of the Assembly Committee on Labor and Employment in June.

SB 553 would:

- Require employers to maintain a Violent Incident Log of all violent incidents against employees including post-incident investigations and response;

- Require all non-healthcare employers to provide active shooter training;

- Require retail employers to provide shoplifter training;

- Prohibit employers from maintaining policies that require rank-and-file, non-security personnel to confront suspected active shoplifters;

- Include, as part of the existing Injury and Illness Prevention Program (IIPP), an assessment of staffing levels as a cause for workplace violence incidents;

- Requires employers to include an evaluation of environmental risk factors in their Workplace Violence Prevention Plan.

- Allow an employee representative to be a petitioner for a workplace violence restraining order;

- Require employers to refer workers to wellness centers.

The California Chamber of Commerce, the California Restaurant Association, California Grocers Association, California Trucking Association, California State Beekeepers Association, and California Retailers Association. are opposing SB 553. They claim, in part, that the le “the legislation risks the livelihood of small-business owners who will have to hire security personnel and is too sweeping to work for all industries.” Much of their opposition seems to focus on a vague requirement for dedicated security personnel, and whether that means a security guard or employees with special training. The business organizations argue that it would be prohibitively expensive for every small business to hire a separate security guard.

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined House […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Office Violence in Retail Institutions Lined by OSHA? Confined House […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]

[…] Is Office Violence in Retail Institutions Lined by OSHA? Confined House […]

[…] Is Workplace Violence in Retail Establishments Covered by OSHA? Confined Space […]