OSHA State Plan states — you can’t live with ’em, you can’t live without ’em.

Or can you?

A labor union has petitioned federal OSHA to withdraw the state’s authority to run its own OSHA program. The union believes that federal OSHA can more effectively protect workers than the state’s OSHA program. The union’s petition was based on data that OSHA compiles, much of it readily available to the public.

Below we will look at what’s going on in South Carolina. What options does OSHA have if a state is not effectively running its OSHA program? Why do we even have state OSHA programs? And what can be done to improve OSHA’s oversight over state OSHA programs?

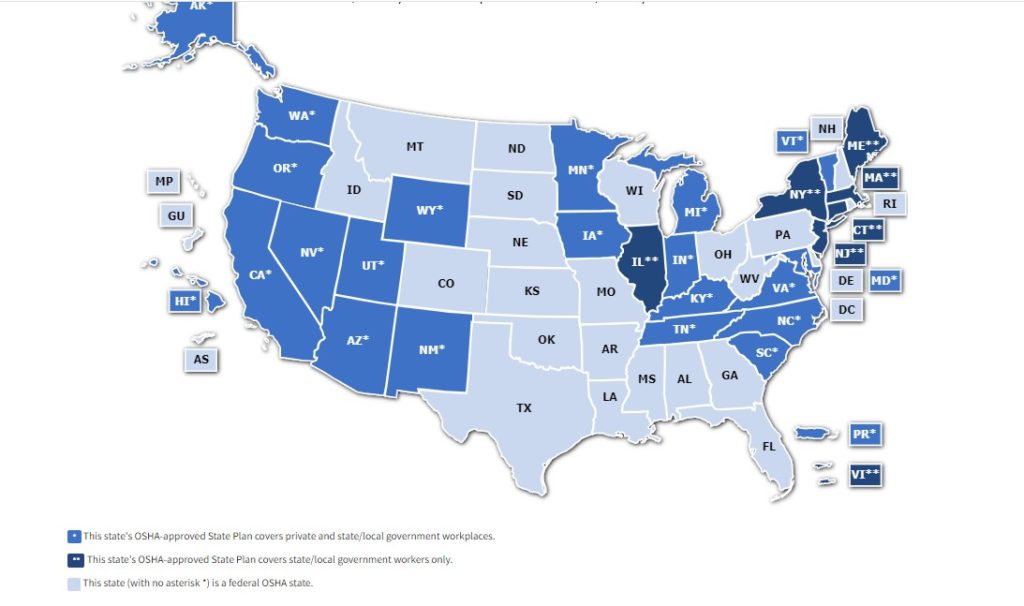

The Occupational Safety and Health Act allows states to run their own OSHA programs as long as those programs are “at least as effective as” the federal OSHA program. Federal OSHA is supposed to oversee those 22 programs (21 states and Puerto Rico) to ensure that they are at least as effective. The law also requires the federal OSHA budget to provide up to 50% of the costs of running the state OSHA programs.

But for a variety of reasons, federal OSHA is failing to use the data it collects on state plan operations to ensure the effectiveness of state plans, instead leaving it to a union representing South Carolina workers to point out the state program’s critical flaws.

In a petition sent to OSHA on December 7, the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW), an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), requested that federal OSHA revoke South Carolina’s state plan “because the Plan has failed to maintain an effective enforcement program.” The union believes that federal OSHA can better protect workers than the state’s program.

There are substantial disparities between the level of protection provided to workers by SC OSHA and that provided by either Federal OSHA or state plans in neighboring southern states.

Despite regularly noting these deficiencies in monitoring the State Plan, OSHA has allowed the disparities in enforcement to grow increasingly wide, so now the State Plan consistently fails to meet the requirements of the Occupational Safety & Health Act (OSH Act) and OSHA regulations.

The union also held a rally to publicize the union’s petition.

The petition marked USSW’s latest challenge to the South Carolina OSHA. In April, USSW filed a civil rights complaint that accused the agency of racial discrimination by failing to routinely inspect workplaces with disproportionately large numbers of Black employees.

South Carolina is also one of the few states that initially failed to adopt OSHA’s 2021 Emergency Temporary Standard to protect heath care workers from COVID-19. Later, when OSHA issued its “test of vaccinate” emergency COVID standard in 2021, South Carolina Govern Harry McMaster tweeted “Rest assured, we will fight them to the gates of hell to protect the liberty and livelihood of every South Carolinian.”

(McMasters promise was realized when the Gates of Hell Supreme Court overturned the standard.)

The effectiveness of OSHA state plan programs is important — not just because South Carolina workers are not adequately protected from workplace health and safety hazards — but because state OSHA plans cover workers in 21 states — almost half the country. And if federal OSHA doesn’t adequately enforce the requirement that these states run effective programs, tens of millions of American workers will receive inferior protections at work.

What’s the Problem in South Carolina?

Much of the USSW/SEIU petition was based on data that OSHA compiles for the agency’s recent Federal Annual Monitoring Evaluation Report (FAME) which is available on OSHA’s website. Other data that OSHA collects, but does not publish, was also used to compile the petition.

OSHA writes the annual FAME reports to evaluate how state plans are performing compared to the federal program. The data in the South Carolina report revealed a number of significant deficiencies. The union used OSHA data to compare SC OSHA’s performance with the federal OSHA program as well as comparing South Carolina to several neighboring states: Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

The effectiveness of OSHA state plan programs is important — not just because South Carolina workers are not adequately protected from workplace health and safety hazards — but because state OSHA plans cover workers in 21 states — almost half the country.

The findings are upsetting:

- South Carolina Has an Inadequate Enforcement Presence

Enforcement presence is the number of safety and health inspections conducted, as compared to the number of employer establishments in the state. South Carolina’s enforcement presence was 50 percent below the acceptable level set by federal OSHA. And, according to the union report, in 2022, SC OSHA’s enforcement presence “dropped to an abysmal 0.32%”.

- SC OSHA’s Penalty Levels Do Not Meet Federal Requirements

Serious safety violations recently carried weaker sanctions in South Carolina than required.. The state’s average serious penalty is $2,019 for all private sector employers, falling well below the national average of $3,259.

Background: On average state plan penalty levels are lower than federal OSHA’s. Current state plan penalties for a serious violation average $2,372 for all state plans put together. Oregon lags way back in last place with an average penalty of $604 — hardly “at least as effective” as federal OSHA by anyone’s definition. And my own state of Maryland isn’t much better with an average penalty of $892.

(In Oregon’s defense, the state legislature just passed a number of measures that should significantly increase penalties to some of the highest in the nation. The new law will come into effect next year so we shall see how it works. Maryland should follow Oregon’s example.)

- South Carolina Conducts Too Few Inspections.

South Carolina conducted 287 inspections in 2022, or about 1.9 for every 1,000 establishments — a figure the union said is less than one-third the rate in the surrounding states of North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia, and far fewer than the national average. SC OSHA failed to conduct on-site inspections in response to more than 378 formal complaints.

- South Carolina Has Too Few Inspectors to Maintain an Effective Enforcement Program.

The report notes that over time, the number of SC OSHA inspectors has declined, even as the state population has increased. South Carolina has admitted that it cannot conduct the expected number of inspections until it increases its staffing, yet its staffing levels have remained consistently below Federal benchmarks since 2017.

- SC OSHA Fails to protect workers rights

The state OSHA doesn’t protect workers against retaliation. The program also fails to allow workers who file complaints to participate in the complaint process by using the designated walkaround representative during SC OSHA inspections or participate in closing conferences where the results of the inspection are reviewed by OSHA

- South Carolina Fails to Issue Citations Under the State OSHA’s General Duty Clause for Heat, Violence and Other Hazards

And not just heat and violence. The union conducted a search of OSHA’s IMIS data for South Carolina shows no evidence of any General Duty Clause violations regarding any hazards in any industry for the last decade. Being as it takes OSHA so long to issue standards, the failure to employ the General Duty Clause leaves workers exposed to serious hazards.

- South Carolina Fails to Initiate Formal Inspections and Phone/Fax Investigations in a Timely Manner.

OSHA is supposed to respond quickly to formal worker complaint, those signed by workers. But OSHA also has the option of addressing complaints using a phone/fax method where OSHA will contact the employer after a complaint and simply ask them to fax (or these days e-mail) proof that there is no violation, or that the violation has been corrected. Where that evidence is not convincing or disputed by the complainant, OSHA is supposed to conduct a physical inspection.) The union has analyzed the OSHA data and determined that SC OSHA does too few on-site inspections and too many phone-fax investigations.

In addition, order to protect workers, OSHA needs to respond quickly to worker complaints. If these inspections are not conducted, or are not done in a timely manner, workers get hurt. The SEIU investigation found that SC OSHA takes an unreasonably long period of time to respond to complaints.

- South Carolina OSHA Fails to Cite Employers for Workplace Health Hazards.

The state doesn’t successfully target the workplaces with the most hazards and fails to identify health hazard violations at the same rate as federal OSHA

- South Carolina Frequently Vacates or Reclassifies Violations When Employers Contest Citations.

Employers always have a right to contest OSHA citations, and OSHA may reduce or completely vacate the citations. But the union found that South Carolina vacates a far higher share of violations issued to private sector employers that contest the agency’s citations compared to North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia and to the national average for all state plans.

What if State OSHA Programs are not at least as effective?

The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires states to run programs that are “at least as effective as” (ALEA) the federal program, but the law does not define exactly what “at least as effective as” actually means. Disputes over what measures constitute ALEA remain fiercely fought to this day. The battles tend to be fought over whether Federal OSHA and the states are equal partners, or — as the law envisioned– whether the connection is more akin to a parent-child relationship.

Some requirements are obvious: States must afford workers the same rights as the federal law provides and they must have designate a responsible agency to run the program. The states must also have a whistleblower program to protect workers from employer retaliation against workers for exercising their rights under the law. And state plans must cover public employees. (Public employees are not covered by federal OSHA.)

Another relatively clear requirement is that all state programs must adopt OSHA standards that are either identical or more effective that federal standards. Federal OSHA has a process for determining whether state standards are at least as effective.

But it gets fuzzier after that. How well funded does the state agency have to be? How many inspectors are required? How many inspections does it need to conduct? How is the inspection and enforcement process conducted? What penalty levels must states impose? Do the states need to participate in federal OSHA’s National Emphasis Programs?

OSHA has few practical tools to use when it determines that an OSHA state plan — or even important parts of a state program — do not meet federal standards. OSHA’s chief enforcement tool is withdrawal of approval of the state plan — in other words, the death penalty,

OSHA has few practical tools to use when it determines that a plan — or even important parts of a state program — do not meet federal standards. OSHA’s chief enforcement tool is the “death penalty” — withdrawal of approval of the state plan — for “failure to comply substantially with any provision of the plan” or where a state plan “consistently fails to provide effective enforcement of standards.” That leaves OSHA little flexibility to work with recalcitrant states.

And in those rare circumstances where OSHA decides to rescind part or all of a state OSHA program, the legal process is exceedingly burdensome and lengthy making withdrawal an impractical threat in all but the most egregious circumstances. The Protecting America’s Workers Act, currently pending before Congress, would make it easier for OSHA to withdraw a state plan and provide the agency with more flexibility for sanctions it can take to correct underperforming states.

Finally, there are serious disadvantages for OSHA and for workers to revoking a state program. Revoking a state plan adds to federal OSHA’s already strained budget. States provide half of the funding for their state OSHA programs, so revoking the program would transfer those costs to federal OSHA. Also, public employees only receive OSHA coverage under state plans. Revoking a state plan would mean that public employees — workers who do work on dangerous roads, wastewater treatment plants, hospitals, mental health institutions, parks and other hazardous workplaces — would lose their right to a safe workplace unless the state decides to adopt a public employee-only plan.

OSHA has never revoked a state OSHA plan, although it came close to revoking North Carolina’s plan after the 1991 Hamlet chicken processing plant fire that killed 25 workers trying to escape the inferno through locked emergency exit doors. North Carolina state OSHA had never inspected the plant in its 11 years of existence.

State OSHA Program Oversight Issues

Federal OSHA has a hard time effectively overseeing state plan programs. OSHA doesn’t have the staff to effectively oversee 21 state programs, and the staff assigned to oversee state plans are often the least experienced. Most reporters covering state safety and labor issues don’t even know that the FAME reports exist and have a hard time deciphering them when they try. The FAME reports are often weighed down by sleep-inducing inside-OSHA jargon and frequently bury serous problems in the mind-numbing inner pages of the reports.

The Executive Summary of the 2021 South Carolina FAME report, for example, paints a very different picture than the SEIU petition — or the body of the report. The Executive Summary of the South Carolina report states that “FY 2021 was a productive year for SC OSHA.” It praises the state’s “restructuring allowed for a more formalized team approach, which made collaboration easier and facilitated success in reaching most of the State Plan’s strategic goals.” The report also has kind words to say about the agency’s “improved website, revising operational documents, amending internal policies for uniformity, and developing and implementing virtual training programs and videos.”

Most reporters covering state safety and labor issues don’t even know that the FAME reports exist and have a hard time deciphering them when they try. The FAME reports are often weighed down by sleep-inducing inside-OSHA jargon and frequently bury serous problems in the mind-numbing inner pages of the reports.

Not until you read further down do you find that the Executive Summary mentions that “A total of two findings were identified; one was a new finding, and one was continued from the previous FAME. This report also includes a total of three observations, two continued and one new.”

“Findings” are much more serious than “observations” and come with “recommendations” for correction.

But you have to dive deeper into the report to figure out what those “findings” and “observations” are: one “finding” is for the state’s failure to adopt much higher maximum penalties mandated by Congress in 2015, and the second “finding” is for deficiencies in SC OSHA’s enforcement of health hazards.

In 2015, Congress passed budget containing language requiring a significant increase in maximum OSHA penalties. Several states, including South Carolina, have still not adopted the higher penalty levels. South Carolina OSHA claims that it is powerless to adopt the 2015 penalties because penalties are written into the South Carolina law, meaning the state legislature must act to update the penalties. And the legislature has not acted.

But this is not an issue of helplessness that can be blamed on a few obstinate legislators. The state of South Carolina filed a lawsuit in 2022 seeking to prevent federal OSHA from forcing the state to increase maximum fines for workplace safety violations. But US District Judge Sherri Lydon concluded that OSHA’s decision in 2022 requiring state workplace safety program maximum fines to match federal maximums wasn’t “a reviewable agency action under the Administrative Procedure Act.”

And then there are other hidden problems that don’t apparently reach a high enough level of concern to be rated as a “finding,” or even an “observation.” For example, much further down, the report states that “SC OSHA’s staffing levels were below the established benchmarks for the program” and that the state’s current penalty per serious violation in the private sector was too low for both large and small employers.

The Obama Administration Attempted to Crack Down

These struggles with the state plans are nothing new. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s federal OSHA had taken a rather laissez-faire attitude toward the state plans, with little significant oversight. Both OSHA Assistant Secretaries during the Clinton administration had been former state plan administrators who were loathe to hold the states responsible.

The “W” Bush administration was not interested in risking support of the business community by cracking down on any state plan problems. And of course the Trump administration was not inclined to address serious problems in some states.

One of my first acts as Acting Assistant Secretary for OSHA in 2009 was to call for a special study of Nevada’s state program. During an 18-month period between 2006 and 2008, 12 construction workers died on the Las Vegas strip. Alexandra Berzon, a young reporter at the Las Vegas Sun, wrote a series of Pulitzer Prize winning investigative pieces on the fatalities. Berzon’s investigation identified many failures in Nevada OSHA’s enforcement program, including the finding that Nevada OSHA “would cite safety violations contributing to deaths on the job, but later, in private meetings with the contractors, would often withdraw the citations or water them down.”

At one point in 2008, union workers walked off their jobs to protest unsafe conditions and the House Education and Labor Committee held hearings in 2009 and 2010 on the working conditions on the strip.

OSHA’s Nevada study identified serious problems with the state’s program, and more troubling, could not assure that many other state plan states did not have the same problems. This led to special studies of all the state plans to identify serious issues.

OSHA’s Nevada investigation identified serious problems with the state’s program, and more troubling, could not assure that other state plan states did not have the same problems. This led to special studies of all the state plans to identify serious issues.

As a result of the studies, OSHA’s Federal Annual Monitoring and Evaluation (FAME) Reports, which evaluate the state plans’ performance against a number of benchmarks comparing a state’s performance against the federal program became much more comprehensive. An effort was also made to write the FAME reports in plain English. The goal was to make the reports more comprehensible so that they would tell a clear story that workers, politicians, and reporters could readily understand, instead of just a collection of difficult-to-understand data. (That effort seems to have faded in ensuing years.)

Among the other conflicts between federal OSHA and the state plans during the Obama administration were federal OSHA’s attempts to bring state plan penalties up to near federal penalty levels. As mentioned above, the average penalty levels of several states were far below the federal average. At the beginning of the Obama administrations, OSHA’s average penalty for a serious violation was somewhere above $2000, while the state plans were, on average, significantly less. Oregon and South Carolina the lowest penalty averages of all the state plan states, in the low hundreds of dollars. Oregon officials argued that because they inspected a higher percentage of workplaces than federal OSHA, they considered themselves to be “at least as effective” as federal OSHA even if their penalties were almost non-existent.

(Federal OSHA disagreed, arguing that if the penalty for violating an OSHA standard was negligible, it didn’t matter how many businesses were inspected. Insignificant penalties equal insignificant deterrence.)

Another conflict fought during the Obama administration was whether states were required to adopt federal National Emphasis Programs — inspection programs targeting specific hazards or industries. Federal OSHA argued that workers and employers expected a “national” emphasis program to be national, not just applied to the 29 states under federal OSHA jurisdiction.

Federal OSHA also had showdowns during the Obama administration with the state of South Carolina (which unilaterally decided it didn’t need a whistleblower program) and Arizona (which decided it didn’t need to adopt federal OSHA fall protection enforcement policies for residential construction workers.) OSHA threatened to rescind South Carolina’s entire program, and assert federal jurisdiction over Arizona construction sector. While state officials in both states initially defied federal OSHA, they eventually conceded to federal OSHA’s demands because the business community preferred to have the state run the OSHA program than the harder-to-pressure feds.

History of State OSHA Programs

So if they’re so problematic, why do we have state plans anyway?

These days, state plans are often praised as “laboratories of the states” — where local authorities, allegedly more in touch with local concerns than faceless Washington bureaucrats — have the opportunity to create a diversity of effective programs more appropriate to the individual states.

But the actual origin of the state plan option was less benevolent: they were the result of business advocacy for programs they could more easily influence than the federal OSHA program.

Prior to passage of the OSHAct in 1970, many states had their own system of workplace safety regulation. Some were enforceable under state law and many were voluntary. Many of the states’ standards were based on industry consensus standards. Consensus standards are generally developed by industry (employer) associations who reach a “consensus” on safety rules that businesses should follow.

The business community pressured Congress to allow states to adopt their existing consensus standards and enforce them in the way they chose. But the labor movement (and progressive Democrats and Republicans) argued that allowing states to have different standards and different enforcement policies would allow a “race to the bottom” where every state competed for business by offering weaker standards than neighboring states.

In several recent cases where federal OSHA has come close to revoking all or part of a state plan’s jurisdiction as a result of some ideologically driven opposition to an OSHA requirement, the business community has swooped in to right the ship and stop federal OSHA’s takeover.

OSHA historian Charles Noble described the business community’s interest in state plans during the Congressional negotiations over the Occupational Safety and Health Act:

Business support for state-level regulation helped the states make their case. Employer shaped that a joint program would reduce their costs. As one steel industry lobbyist later put it, “everyone knew that the state commissions were in bed with industry and everyone expected that the states would start up plans as soon as they passed.” The state plans would, he expected, be a “safety valve” for employers.

During negotiations over the OSHAct, business and labor eventually reached a compromise, establishing federal OSHA as the primary legal authority but allowing states to run their own state OSHA programs only if the state programs were “at least as effective as” the federal OSHA program.

And indeed, Noble’s characterization my not be far off. As mentioned above, in several recent cases where federal OSHA has come close to revoking all or part of a state plan’s jurisdiction as a result of some ideologically driven opposition to an OSHA requirement, the business community has swooped in at the last minute to right the ship and stop federal OSHA’s takeover. They understood that their best interests would not be served if the state allowed the feds — instead of state government — to control workplace health and safety enforcement.

Conclusion

So. State plan states good? Or state plan states bad?

It’s complicated. For OSHA, with its meagre resources and weak law, it’s difficult to effectively oversee the all 29 full and public employee-only state plans. Consequently, many states run programs that are clearly not as effective as federal OSHA’s. (And even that may be a low barrier. Many question whether federal OSHA, given its antiquated statute, political opposition and tiny budget actually runs a program “effective” enough to pursue its mission of assuring safe workplaces.)

The fact that OSHA’s FAME reports, analyzing the state programs’ effectiveness, are opaque and indecipherable by most humans of reasonable intelligence makes it difficult for reporters or politicians to understand the problems their state plans may have, much less improve them.

As with most problems at OSHA, this can’t be blamed solely on OSHA leadership or staff. There are serious structural issues that keep many states from running effective programs and keep OSHA from conducting adequate oversight. State plan funding is far too low. State OSHA inspectors are often so poorly paid that once they have experience, they flee for better paid corporate (or federal OSHA) jobs. And, as mentioned above, the language of the OSHAct makes it difficult — costly and time consuming — to address shortcomings in state plan administration — even seemingly obvious problems like penalty levels.

Increased funding and improved federal oversight of the states — along with legislative changes to enable OSHA to more quickly and effective address problems — would significantly improve the oversight, value and effectiveness of state OSHA programs.

Ultimately, what we’re seeing now, is that the best tool to oversee the effectiveness of OSHA state programs is not OSHA, but labor unions. And what we’re seeing here is a labor union in a virulently anti-union state raising the issue of OSHA state plan effectiveness to national attention.

On the other hand, there are benefits to state programs. State plans are allowed to have different processes for adopting new standards and a few states that go above and beyond federal OSHA’s standards and enforcement.

Four state plan states, for example, already have heat standards. (California, Oregon, Washington and Minnesota). It will take OSHA many more years to complete a federal heat standard.

California has many standards — respiratory diseases, workplace violence, ergonomics, heat and others — that federal OSHA doesn’t have. Virginia (then under a Democratic administration) was the first state to issue an emergency standard to protect all workers from COVID-19 — before federal OSHA issue a standard (which only covered healthcare workers.)

And whereas federal OSHA cannot force an employer to correct a hazard until an employer contest is resolved (which can be months or years), Washington state OSHA can require employers to abate a hazard even during the often lengthy contest period.

OSHA collects an enormous amount of data to make determinations about the effectiveness of state programs. That evidence should be used for more than just a cure for insomnia.

In conclusion, OSHA state programs are somewhat of a mixed bag — and, speaking as a former Deputy Assistant Secretary — a major pain in the neck to oversee. But strict oversight is important. Taking action against even one recalcitrant state plan sends an important message to the other states that weak programs will not be tolerated. OSHA spends a lot of resources collecting an enormous amount of data to make determinations about the effectiveness of state programs. That work and evidence should be used for more than just a cure for insomnia.

So, kudos to USSW and SEIU. Job well done.

But really, this is a job OSHA should be doing.