It’s once again time to remind everyone of one of the nation’s most tragic — and least known — injustices: This country’s failure to protect the lives of over eight million of the country’s public employees — the workers who make life in this country livable. Fifty-five years after Congress declared passed a law committing “to assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the Nation safe and healthful working conditions,” public employees in 23 states public employees inexplicably remain second class citizens, without the right to a safe workplace, without the right to come home alive and well at the end of the workday.

Over the past few weeks, at least four public employees have been killed in states with no OSHA coverage for public employees. (This list excludes several law enforcement officers and firefighters who are killed doing their jobs each week. For example, over the past two weeks, at least 6 law enforcement officers and firefighters have died on the job.)

- Paul Linville was killed in an apparent trench collapse in Milton, West Virginia.

- Chase Cupp, a Scott City, Kansas, public workers employee was killed in a workplace accident on July 18. It is unclear how Cupp died. According to news reports, he was found dead by another employee at the city’s water tower.

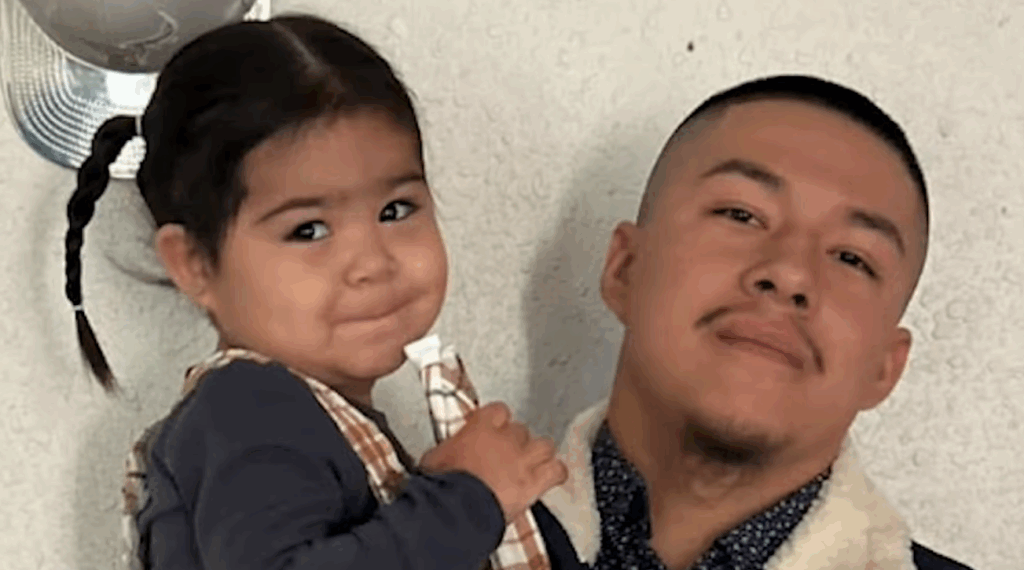

- Robert Saucedo, 23, suffered what was described only as a “fatal injury” while making repairs to the leak in Sweetwater, Texas. It is unclear how Saucedo died, but in an interview with Saucedo’s mother-in-law, said the incident involved a saw.

- Levi Phillips, 58, a Street Department employee was killed in a single-vehicle crash in Alexandria City, Louisiana. Phillips was taken to a local hospital, where he died from his injuries.

Who Investigates?

Good question. Will we ever know how or why Linville, Cupp, Saucedo or Phillips died, or how their deaths could have been prevented? Don’t hold your breath.

At least one West Virginia news organization is asking the right questions.

When a WSAZ reporter asked Milton, West Virginia Mayor Shane Evans and Public Works Manager Mike Ramsey if the city will be investigating Linville’s death, they told WSAZ that the incident was being investigated by “rural water.”

No one knew what they meant by that. Evans later responded that “I don’t even know if there is an investigation. I don’t know who is supposed to investigate.”

Ramsey apparently confirmed the city is not currently investigating. “When asked if there would be an investigation, he responded, ‘I don’t see why not.’”

Actually, no one knows who will be investigating the West Virginia public employee deaths, because there is no OSHA coverage of local government employees in West Virginia, and therefore no objective agency that conducts any kind of investigation into the deaths of public employees.

Actually, no one knows who will be investigating, because there is no OSHA coverage of local government employees in West Virginia, and therefore no objective agency that conducts any kind of investigation into the deaths of public employees. According to WSAZ, other agencies and organizations that will not be investigating include the West Virginia Division of Labor, West Virginia State Police, West Virginia Public Service Commission, Cabell County Sheriff’s Office, and West Virginia Rural Water Association.

WSAZ also submitted a Freedom of Information Act request for work order, safety equipment and gear being used as well as safety protocols for these types of jobs.

At least one West Virginia Republican state legislator are unhappy with the current situation.

State Delegate Dana Ferrell, R-Kanawha, who is the Chair of the House Local Governments Committee, told WSAZ that he’s considering legislation to prevent something like this from happening again.

“My heart goes out to the family and friends of the Milton city worker that was killed on the job last week,” Ferrell said in a statement to WSAZ. “This accident is absolutely tragic and, as public officials, it is our job to do all we can to make sure incidents like this never happen again.”

“In my capacity as chair of the House Local Governments Committee, I plan to do a full review of our state and local safety regulations to ensure the highest standards are upheld to protect our state’s workers,” the statement concludes.

Strangely, a law passed in West Virginia in 1998 does provide some health and safety protections for state employees in West Virginia (except workers in the Departments of Corrections, Health and the Legislature), but not for employees of cities and counties. The bill does state that cities and counties “may” pass ordinances that “elect” to cover “some or all of its workplaces or employees.” (This is not a federally approved program because it is not “at least as effective” as federal OSHA.)

But a West Virginia labor official confirmed to me that in 2015, five counties opted in to public employee OSHA coverage, and then opted out the next year. Meanwhile, no state agencies have been cited for any health and safety violations over the past five years. You can draw your own conclusions about the effectiveness of West Virginia’s public employee OSHA program.

Albany Georgia: A culture of negligence, cost-cutting, and disregard for worker safety

As you may know if you’ve been reading Confined Space long enough, I’ve been extremely skeptical of cities doing their own investigations. When investigations do take place, they are often not released, or simply blame the workers.

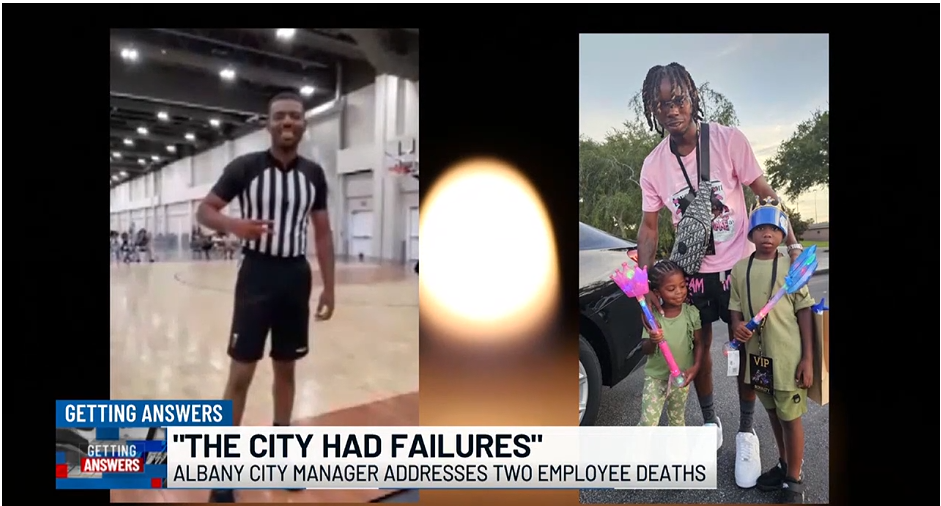

Luckily, WALB News in Albany had an intrepid investigative reporter, Lenah Allen, who fearlessly pursued the reasons behind the recent deaths of Darrious Stephens and Sebastian Dykes Jr. last year. Allen has moved on, but WALB reporter Jamie Worsley has picked up the story. She reported last month that the City of Albany had issued newly updated and developed safety protocols in response to the deaths of Stephens and Dykes. To prevent trench collapses like the one that killed Dykes, the protocols require the Public Works department to use trench boxes in any trench more than 4-feet deep. (OSHA’s trenching standard requires trench boxes or other protective measures in trenches deeper than 5 feet.)

According to Worsely, the old Standard Operations Procedures (SOPs) from 2014 on sewer lines do not mention the use of trench boxes at all, just general safety devices.

A memo summarizing the investigation into Dykes’ death by the city’s police department revealed “a lack of proper safety equipment, inadequate training, and repeated dismissal of safety concerns by management” in the death of Dykes. A hard-hitting memo from police officials to the city noted that “Crew supervisors raised concerns about unsafe working conditions and the need to contract out dangerous jobs, but their recommendations were ignored by upper management due to cost considerations.”

The investigation concluded that the incident was preventable. It highlighted a culture of negligence, cost-cutting, and disregard for worker safety that created an environment where such tragedies were inevitable.

The memo also noted that

The investigation concluded that the incident was preventable. It highlighted a culture of negligence, cost-cutting, and disregard for worker safety that created an environment where such tragedies were inevitable. Management’s failure to address known hazards and provide essential resources directly contributed to the loss of life and the physical and emotional harm experienced by the crew.

No report was released regarding Stephen’s drowning, although new SOPs were also issued that included requirements to

- Avoid working in inclement weather or low visibility unless necessary.

- Use a buddy system whenever possible.

- And use whistles, radios, life preservers and grab lines during an emergency.

One Albany worker was not impressed.

Al Watts worked for Albany Public Works for 13 years.

He says these protocols sound good on paper but are too little, too late for his dear friend, Darrious.

“The life jackets, you know, for collecting samples, that that’s a great thing that should have already been in place, but still… them addressing the stability of the platform to where you collect samples for, that’s not even addressed because they’re still collecting samples on unstable ground. My issue is jobs being too big that need to be contracted out that are not being contracted out. You’re forcing your employees to do jobs that they don’t have the right equipment to do,” Watts says.

The city also received approval to hire seven new safety officers to enforce safety protocols for the city’s nearly 1,100 employees.

Why are public employees second class citizens?

Had Linville been killed about a half hour west, in Kentucky, or if Saucedo had been killed a few hours over the state line in New Mexico, OSHA would be conducting an investigation,

Why do public employees, working just a few miles apart across an arbitrary state border line have drastically different protections in this country? Why are public employees legally allowed to get hurt and die in unsafe workplaces when they do the same — or more dangerous work as private sector employees?

Welcome to the weird world of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHAct). The OSHAct, passed by Congress in 1970, required employers to provide a safe workplace for their employees. Employers were required to comply with OSHA standards and face inspections if a worker complained, or someone was hurt or killed in the workplace.

But with a major exception: public employees were not covered by the OSHAct. They have no legal right to a safe workplace, even though many did the exact same work that private sector workers di. Even though state and local government employers have a higher injury and illness rate than private industry workers, including construction, mining and manufacturing workers.

There were two exceptions to the public employee exemption.

First, states were allowed to run their own OSHA programs — 50% funded by federal OSHA — if their programs were “at least as effective” as federal OSHA’s. And those state plans are required to cover public employees in their state.

States were also allowed to adopt “public employee-only plans” where federal OSHA would provide 50% of the funding for those states to cover only their public employees. The feds then continue to cover the private sector in those states.

There are 21 states (and Puerto Rico) that run their own full state plans, and another 6 states (and the Virgin Islands) that have public employee-only plans, leaving 23 states where public employees have no OSHA coverage, no right to come home alive and healthy at the end of the work day. Workers in Washington DC also have no OSHA coverage.*

Why haven’t more states passed public employee OSHA laws? If you listen to organizations like the League of Cities, Conference of Mayors and National Association of Counties, who all oppose public employee coverage, it’s because public employers are already doing a wonderful job protecting their employees and they don’t need any more burdensome laws and standards standards to tell them to do what they’re already doing.

Also, they argue, OSHA coverage would cost too much for strapped government budgets. Not a good use of taxpayer dollars.

Of course, they never answer the question of how something they’re allegedly already doing can cost too much to do?

The Big Picture

Kudos to the City of Albany for conducting a real investigation into Dykes’ death — as well as the underlying causes — but what about the hundreds of thousands of other Georgia public employees and the millions in the other 22 states that provide no OSHA coverage for public employees? Do all of those states and counties and cities need to be shocked into doing the right thing by the preventable deaths of their employees? Have any Georgia state legislators introduced legislation that would cover their states’ public employees?

Last year, Congressmen Chris Deluzio (D-PA) and Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) introduced the bipartisan Public Service Worker Protection Act, which would bring all of the nation’s public employees under OSHA protection. The bill was re-introduced this year as H.R. 3139. The bill has 35 co-sponsors (Fitzpatrick remaining the only Republican), but that list does not include any Kansas, West Virginia or Georgia Representatives, including Congressman Sanford Bishop (D-GA), who represents the city of Albany.

An identical bill, S.1881, has been introduced in the Senate. That legislation has no Republican co-sponsors.

One state that already covers public employees is improving protections. After the recent deaths of several Maryland public employees, the Maryland Senate and House passed the Davis Martinez Public Employee Safety and Health Act. Maryland is an OSHA state plan state, so public employees were already covered by OSHA (unlike public employees in 22 other states.) But Maryland does not issue financial penalties when public employers are cited. So even though Maryland OSHA cited the city of Baltimore after the heat-related death of public works employee Ronald Silver II in 2024, no penalty was issued. The Davis Martinez Act provides for penalties against Maryland public employers, creates a Public Employee Division in Maryland OSHA, and requires the state to issue a standard to protect public employees from workplace violence. Davis Martinez, after whom the bill is named, was a Maryland parole officer who was killed last year by a registered sex offender he was monitoring.

The muscle behind both the Maryland legislation, as well as the Public Service Worker Protection act was provided largely be labor unions representing public employees. But most of the states without public employee OSHA , also have little public employee union representation. (Another serious human rights problem worthy of more attention.)

Thoughts and Prayers Aren’t Enough

In a Facebook post, the city of Milton said,

“The City of Milton extends our deepest sympathy to the family and friends of Paul Linville. Paul was not only an exceptional employee, but also a great man and a friend that everyone could count on. His kindness, dedication, and warm spirit touched so many lives in our community. He will be terribly missed, but his memory and impact he made will live on in the hearts of all who knew him. Our thoughts and prayers are with his loved ones during this difficult time.”

And the Mayor described him as “like family to all of us.”

But thoughts and prayers aren’t enough. If the state had provided OSHA coverage for public employees, and if the city had been in compliance with OSHA trenching standards, Paul Linville would be alive today. That’s not how we treat family members.

If West Virginians (and those of 22 other states) really want to protect their family members, friends and co-workers who work for cities and counties around the state, they should force their representatives to pass a law providing OSHA protections to public employees — or urge their Congressional Representatives and Senators to pass a national law to protect all of the nation’s public employees.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 created OSHA to protect workers, but it explicitly leaves state and local government employees outside federal OSHA’s reach. Section 3(5) of the law defines “employer” in a way that excludes state and local governments, so Congress chose not to impose federal workplace rules on state-run operations.

Why that matters:

– Federalism: Congress respected states’ sovereignty by not regulating their internal workforce.

– Practicality: OSHA focuses limited federal resources on the private sector, where most workplace injuries occur.

– Flexibility: States can design and enforce safety programs that fit local needs—and many have their own plans that cover public employees and sometimes set tougher standards.

Bottom line: federal OSHA protects private-sector workers, while states retain the authority (and responsibility) to protect their own public employees through state-run programs.

Those were certainly some of the reasons. Another was that in 1970 there were no public employee unions with the power to push Congress to cover their members. And it’s true that “states retain the authority (and responsibility) to protect their own public employees through state-run programs.” And that’s the problem: Far too many states have shirked the responsibility to protect their public employees. And we have too many preventable injuries, illnesses and death because of it.

Thank you, Jordan, for this cogent rundown of a horrible situation.

Rena

It is inconceivable to me that so many states do not have OSHA-like programs for public employers. I spent the last 16 years working with Utah’s public employers, as a UOSH Consultant. I spent 8 years before that as a CSHO, investigating both public and private employers. I am here to tell you that public employers can be as clueless as the private employers that I also helped as a Consultant. Just because it is a city, county or state running the work, does not mean they know anything about protecting their employees. Utah has been a State Plan for 40 years, this year. We still strive to protect ALL employees at their workplace.